The Cold War and Colonial Independence

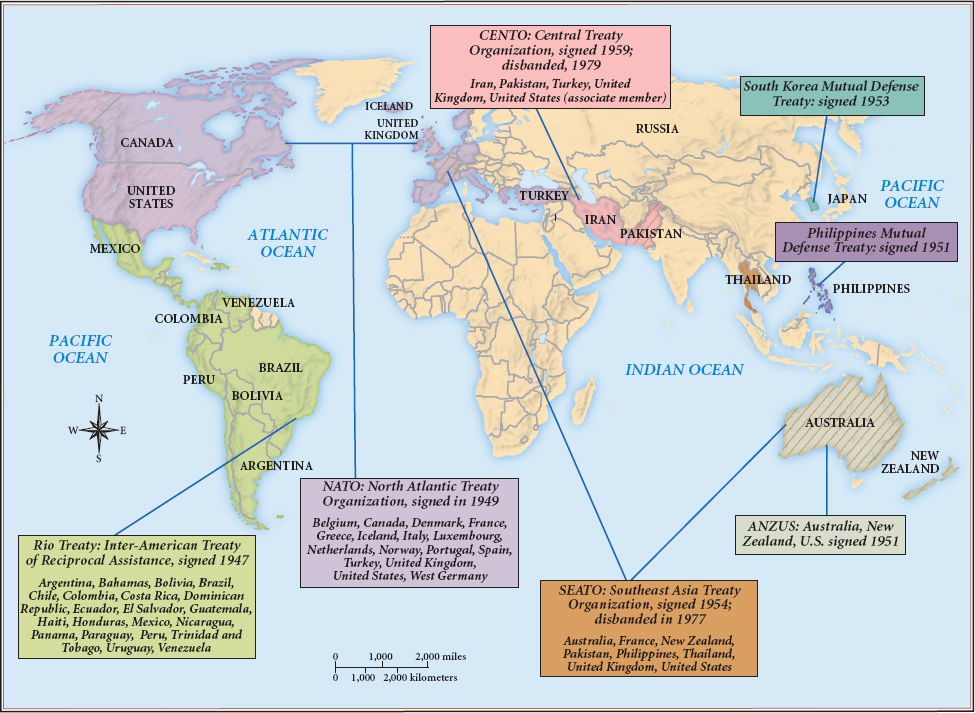

Insisting that all nations had to choose sides, the United States drew as many countries as possible into collective security agreements, with the NATO alliance in Europe as a model. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles orchestrated the creation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), which in 1954 linked the United States and its major European allies with Australia, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand. An extensive system of defense alliances eventually tied the United States to more than forty other countries (Map 25.5). The United States also sponsored a strategically valuable defensive alliance between Iraq and Iran, on the southern flank of the Soviet Union.

Despite American rhetoric, the United States was often concerned less about democracy than about stability. The Truman and Eisenhower administrations tended to support governments, no matter how repressive, that were overtly anticommunist. Some of America’s staunchest allies — the Philippines, South Korea, Iran, Cuba, South Vietnam, and Nicaragua — were governed by dictatorships or right-wing regimes that lacked broad-based support. Moreover, Eisenhower’s secretary of state Dulles often resorted to covert operations against governments that, in his opinion, were too closely aligned with the Soviets.

For these covert tasks, Dulles used the newly created (1947) Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), run by his brother, Allen Dulles. When Iran’s democratically elected nationalist premier, Mohammad Mossadegh, seized British oil properties in 1953, CIA agents helped depose him and installed the young Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as shah of Iran. Iranian resentment of the coup, followed by twenty-five years of U.S. support for the shah, eventually led to the 1979 Iranian Revolution (discussed in Chapter 30). In 1954, the CIA also engineered a coup in Guatemala against the democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, who had seized land owned by the American-owned United Fruit Company. Arbenz offered to pay United Fruit the declared value of the land, but the company rejected the offer and turned to the U.S. government. Eisenhower specifically approved those CIA efforts and expanded the agency’s mandate from gathering intelligence to intervening in the affairs of sovereign states.

Vietnam But when covert operations and coups failed or proved impractical, the American approach to emerging nations could entangle the United States in deeper, more intractable conflicts. One example was already unfolding on a distant stage, in a small country unknown to most Americans: Vietnam. In August 1945, at the close of World War II, the Japanese occupiers of Vietnam surrendered to China in the north and Britain in the south. The Vietminh, the nationalist movement that had led the resistance against the Japanese (and the French, prior to 1940), seized control in the north. But their leader, Ho Chi Minh, was a Communist, and this single fact outweighed American and British commitment to self-determination. When France moved to restore its control over the country, the United States and Britain sided with their European ally. President Truman rejected Ho’s plea to support the Vietnamese struggle for nationhood, and France rejected Ho’s offer of a negotiated independence. Shortly after France returned, in late 1946, the Vietminh resumed their war of national liberation.

Eisenhower picked up where Truman left off. If the French failed, Eisenhower argued, all non-Communist governments in the region would fall like dominoes. This so-called domino theory — which represented an extension of the containment doctrine — guided U.S. policy in Southeast Asia for the next twenty years. The United States eventually provided most of the financing for the French war, but money was not enough to defeat the determined Vietminh, who were fighting for the liberation of their country. After a fifty-six-day siege in early 1954, the French were defeated at the huge fortress of Dien Bien Phu. The result was the 1954 Geneva Accords, which partitioned Vietnam temporarily at the 17th parallel and called for elections within two years to unify the strife-torn nation.

The United States rejected the Geneva Accords and set about undermining them. With the help of the CIA, a pro-American government took power in South Vietnam in June 1954. Ngo Dinh Diem, an anticommunist Catholic who had been residing in the United States, returned to Vietnam as premier. The next year, in a rigged election, Diem became president of an independent South Vietnam. Facing certain defeat by the popular Ho Chi Minh, Diem called off the scheduled reunification elections. As the last French soldiers left in March 1956, the Eisenhower administration propped up Diem with an average of $200 million a year in aid and a contingent of 675 American military advisors. This support was just the beginning.

The Middle East If Vietnam was still of minor concern, the same could not be said of the Middle East, an area rich in oil and political complexity. The most volatile area was Palestine, populated by Arabs but also historically the ancient land of Israel and coveted by the Zionist movement as a Jewish national homeland. After World War II, many survivors of the Nazi extermination camps resettled in Palestine, which was still controlled by Britain under a World War I mandate. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to partition Palestine between Jewish and Arab sectors. When the British mandate ended in 1948, Zionist leaders proclaimed the state of Israel. A coalition of Arab nations known as the Arab League invaded, but Israel survived. Many Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes during the fighting. The Arab defeat left these people permanently stranded in refugee camps. President Truman recognized the new state immediately, which won him crucial support from Jewish voters in the 1948 election but alienated the Arab world.

Southeast of Palestine, Egypt began to assert its presence in the region. Having gained independence from Britain several decades earlier, Egypt remained a monarchy until 1952, when Gamal Abdel Nasser led a military coup that established a constitutional republic. Caught between the Soviet Union and the United States, Nasser sought an independent route: a pan-Arab socialism designed to end the Middle East’s colonial relationship with the West. When negotiations with the United States over Nasser’s plan to build a massive hydroelectric dam on the Nile broke down in 1956, he nationalized the Suez Canal, which was the lifeline for Western Europe’s oil. Britain and France, in alliance with Israel, attacked Egypt and seized the canal. Concerned that the invasion would encourage Egypt to turn to the Soviets for help, Eisenhower urged France and Britain to pull back. He applied additional pressure through the UN General Assembly, which called for a truce and troop withdrawal. When the Western nations backed down, however, Egypt reclaimed the Suez Canal and built the Aswan Dam on the Nile with Soviet support. Eisenhower had likely avoided a larger war, but the West lost a potential ally in Nasser.

In early 1957, concerned about Soviet influence in the Middle East, the president announced the Eisenhower Doctrine, which stated that American forces would assist any nation in the region that required aid “against overt armed aggression from any nation controlled by International Communism.” Invoking the doctrine later that year, Eisenhower helped King Hussein of Jordan put down a Nasser-backed revolt and propped up a pro-American government in Lebanon. The Eisenhower Doctrine was further evidence that the United States had extended the global reach of containment, in this instance accentuated by the strategic need to protect the West’s access to steady supplies of oil.

IDENTIFY CAUSES