Thinking Like a Historian: The Suburban Landscape of Cold War America

Between the end of World War II and the 1980s, Americans built and moved into suburban homes in an unprecedented wave of construction and migration that changed the nation forever. New home loan rules, and government backing under the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration, made new suburban houses cheaper and brought home ownership within reach of a larger number of Americans than ever before. Commentators cheered these developments as a boon to ordinary citizens, but by the 1960s a generation of urban critics, led by journalist Jane Jacobs, had begun to find fault with the nation’s suburban obsession. The following documents provide the historian with evidence of how these new suburban communities arose and how they began to transform American culture.

- “Peacetime Cornucopia,” The New Yorker, October 6, 1945.

© Constanin Alajalov/New Yorker/Conde Nast Publications.

© Constanin Alajalov/New Yorker/Conde Nast Publications. - Life magazine, “A Life Round Table on Housing,” January 31, 1949.

The most aggressive member of Life’s Round Table, whether as builder or debater, was William J. Levitt, president of Levitt and Sons, Inc. of Manhasset, NY. He feels that he has started a revolution, the essence of which is size. Builders in his estimation are a poor and puny lot, too small to put pressure on materials manufacturers or the local czars of the building codes or the bankers or labor. A builder ought to be a manufacturer, he said, and to this end must be big. He himself is a nonunion operator.

The Levitt prescription for cheaper houses may be summarized as follows: 1) take infinite pains with infinite details; 2) be aggressive; 3) be big enough to throw your weight around; 4) buy at wholesale; and 5) build houses in concentrated developments where mass-production methods can be used on the site.

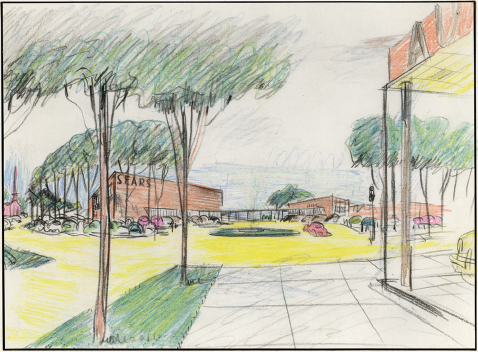

- Site plan sketch for Park Forest, Illinois, 1946.

The Park Forest Historical Society.

The Park Forest Historical Society. - William H. Whyte Jr., The Organization Man, 1956. Whyte, a prominent journalist, wrote about the decline of individualism and the rise of a national class of interchangeable white-collar workers.

And is this not the whole drift of our society? We are not interchangeable in the sense of being people without differences, but in the externals of existence we are united by a culture increasingly national. And this is part of the momentum of mobility. The more people move about, the more similar American environments become, and the more similar they become, the easier it is to move about.

More and more, the young couples who move do so only physically. With each transfer the décor, the architecture, the faces, and the names may change; the people, the conversation, and the values do not — and sometimes the décor and architecture don’t either. …

Suburban residents like to maintain that their suburbia not only looks classless but is classless. That is, they are apt to add on second thought, there are no extremes, and if the place isn’t exactly without class, it is at least a one-class society — identified as the middle or upper middle, according to the inclination of the residents. “We are all,” they say, “in the same boat.”

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961. A classic celebration of vibrant urban neighborhoods by a New York writer and architectural critic.

Although it is hard to believe, while looking at dull gray areas, or at housing projects or at civic centers, the fact is that big cities are natural generators of diversity and prolific incubators of new enterprises and ideas of all kinds. …

This is because city populations are large enough to support wide ranges of variety and choice in these things. And again we find that bigness has all the advantages in smaller settlements. Towns and suburbs, for instance, are natural homes for huge supermarkets and for little else in the way of groceries, for standard movie houses or drive-ins and for little else in the way of theater. There are simply not enough people to support further variety, although there may be people (too few of them) who would draw upon it were it there. Cities, however, are the natural homes of supermarkets and standard movie houses plus delicatessens, Viennese bakeries, foreign groceries, art movies, and so on. …

The diversity, of whatever kind, that is generated by cities rests on the fact that in cities so many people are so close together, and among them contain so many different tastes, skills, needs, supplies, and bees in their bonnets.

- Herbert J. Gans, The Levittowners, 1967. One of the first sociological studies of the new postwar suburbs and their residents.

The strengths and weakness of Levittown are those of many American communities, and the Levittowners closely resemble other young middle class Americans. They are not America, for they are not a numerical majority of the population, but they represent the major constituency of the latest and more powerful economic and political institutions in American society — the favored customers and voters whom these seek to attract and satisfy. …

Although they are citizens of a national polity and their lives are shaped by national economic, social, and political forces, Levittowners deceive themselves into thinking that the community, or rather the home, is the single most important unit of their lives. …

In viewing their homes as the center of life, Levitowners are still using a societal model that fit the rural America of self-sufficient farmers and the feudal Europe of self-isolating extended families.

Sources: (2) Life, January 31, 1949, 74; (4) William H. Whyte Jr., The Organization Man (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 276, 299; (5) Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Westminster, MD: Vintage, 1992), 145–147; (6) Herbert J. Gans, The Levittowners (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 417–418.

ANALYZING THE EVIDENCE

Question

k4CrqEVE/kcvd3GOqdos3e0Q/ejF/oVzglmWWsZm2T7NhN5F6bY1ONI7R0I7V8B26B7zL2g2iAECqJqVjZinkMP/bCeCgbXiCajCPld3KfYNInYj/PfEPqhG/I0t1LFgQuestion

wi3IR7ePZKHFl049N/0UArbK+uIjdqBCv03FHeEwl3dhnGGvvzKsOz5rCJeEVw5D7S631P3cB67IJD04qMLenXvXdifMALmj622AlPtm8XQlnUSP50jq7QwmMrKGqynf+nOM8aD+u/HSbwhnovgiQovYqJVQlw7UVhD2i9/Yr6a8kFfdzNxaqkbEnc8MFoHhgcBzZtpDGAhJgthoxfi5cOqx2nE4l7owspwI9KxOzSlvmCy4Zf1aNb0JtTzmqMtZ4Ncec791Hcs=Question

cPNCOldRXHKkcsg1bpaLS2KwvWATXDMT/BYiqlLQygxHNK+/RFCabhT7ufV4tV6dHfSFeAzimckqlumy8yXzR9UopcfyzpGWzGGiVUAH8osv//0CwAR2q1hEDrmSCdJ2mCqnPgL+TpWdlQFdKMFhkUKAbRBwCs7wLZp+uTVAoXp1COJzlMf6/ulRIa3jNQUsPdXf6aNN7xEADa4w7b+nZttZ7jWYj6bZIFBivWyt9RrnrqrcWSjQ35hlP9gsCLy4abJ9Ydc3qg3UfPraAJMYcA==Question

6J7vVHxQpS9apD4RkglT/R622uMXUxY8xyTODPeBtYpznUEtBnmxdj2lf5TbfkjBtfMoL8lV/C1SxG2BaRNmrjXuisyYzOHCgsVQ1nGgeDTdFm+NerhbI66E6UxGJyk9z79tyowpyLjorTnshhQEAZu6jP2gTCawiyLFLCUNtxxieLI/FO4yVt1gMtsiSgMz7Zzhqgdr9+SnOHT6bOn19uV4al8/8W6IV6IQ9g==

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER