Legislating Civil Rights, 1963–1965

The first civil rights law in the nation’s history, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, came in 1866 just after the Civil War. Its provisions were long ignored. A second law was passed during Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, but it was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. For nearly ninety years, new civil rights legislation was blocked or filibustered by southern Democrats in Congress. Only a weak, largely symbolic act was passed in 1957 during the Eisenhower administration. But by the early 1960s, with legal precedents in their favor and nonviolent protest awakening the nation, civil rights leaders believed the time had come for a serious civil rights bill. The challenge was getting one through a still-reluctant Congress.

The Battle for Birmingham The road to such a bill began when Martin Luther King Jr. called for demonstrations in “the most segregated city in the United States”: Birmingham, Alabama. King and the SCLC needed a concrete victory in Birmingham to validate their strategy of nonviolent protest. In May 1963, thousands of black marchers tried to picket Birmingham’s department stores. Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s public safety commissioner, ordered the city’s police troops to meet the marchers with violent force: snarling dogs, electric cattle prods, and high-pressure fire hoses. Television cameras captured the scene for the evening news.

While serving a jail sentence for leading the march, King, scribbling in pencil on any paper he could find, composed one of the classic documents of nonviolent direct action: “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” “Why direct action?” King asked. “There is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.” The civil rights movement sought, he continued, “to create such a crisis and establish such a creative tension.” Grounding his actions in equal parts Christian brotherhood and democratic liberalism, King argued that Americans confronted a moral choice: they could “preserve the evil system of segregation” or take the side of “those great wells of democracy … the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.”

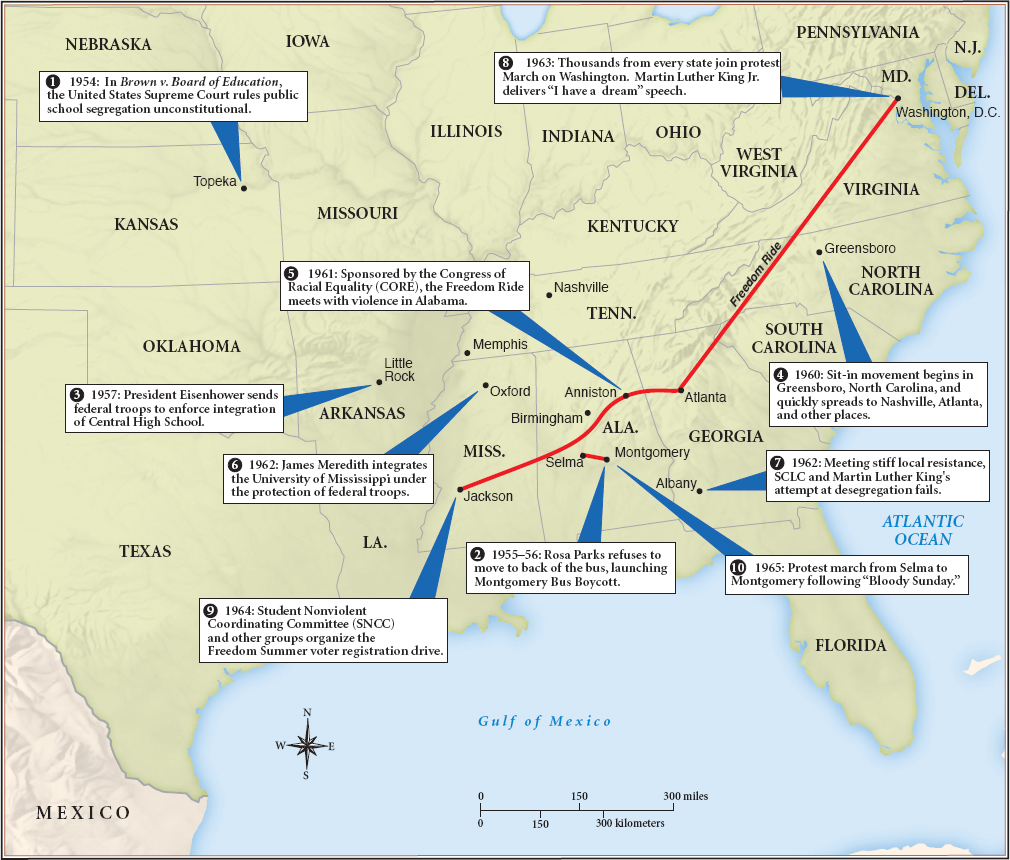

Outraged by the brutality in Birmingham and embarrassed by King’s imprisonment for leading a nonviolent march, President Kennedy decided that it was time to act. On June 11, 1963, after newly elected Alabama governor George Wallace barred two black students from the state university, Kennedy denounced racism on national television and promised a new civil rights bill. Many black leaders felt Kennedy’s action was long overdue, but they nonetheless hailed this “Second Emancipation Proclamation.” That night, Medgar Evers, president of the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP, was shot in the back in his driveway in Jackson by a white supremacist. Evers’s martyrdom became a spur to further action (Map 27.3).

The March on Washington and the Civil Rights Act To marshal support for Kennedy’s bill, civil rights leaders adopted a tactic that A. Philip Randolph had first advanced in 1941: a massive demonstration in Washington. Under the leadership of Randolph and Bayard Rustin, thousands of volunteers across the country coordinated car pools, “freedom buses,” and “freedom trains,” and on August 28, 1963, delivered a quarter of a million people to the Lincoln Memorial for the officially named March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (Thinking Like a Historian).

Although other people did the planning, Martin Luther King Jr. was the public face of the march. It was King’s dramatic “I Have a Dream” speech, beginning with his admonition that too many black people lived “on a lonely island of poverty” and ending with the exclamation from a traditional black spiritual — “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!” — that captured the nation’s imagination. The sight of 250,000 blacks and whites marching solemnly together marked the high point of the civil rights movement and confirmed King’s position as the leading spokesperson for the cause.

To have any chance of getting the civil rights bill through Congress, King, Randolph, and Rustin knew they had to sustain this broad coalition of blacks and whites. They could afford to alienate no one. Reflecting a younger, more militant set of activists, however, SNCC member John Lewis had prepared a more provocative speech for that afternoon. Lewis wrote, “The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the Heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did.” Signaling a growing restlessness among black youth, Lewis warned: “We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together again in the image of democracy.” Fearing the speech would alienate white supporters, Rustin and others implored Lewis to tone down his rhetoric. With only minutes to spare before he stepped up to the podium, Lewis agreed. He delivered a more conciliatory speech, but his conflict with march organizers signaled an emerging rift in the movement.

Although the March on Washington galvanized public opinion, it changed few congressional votes. Southern senators continued to block Kennedy’s legislation. Georgia senator Richard Russell, a leader of the opposition, refused to support any bill that would “bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races.” Then, suddenly, tragedies piled up, one on another. In September, white supremacists bombed a Baptist church in Birmingham, killing four black girls in Sunday school. Less than two months later, Kennedy himself lay dead, the victim of assassination.

On assuming the presidency, Lyndon Johnson made passing the civil rights bill a priority. A southerner and former Senate majority leader, Johnson was renowned for his fierce persuasive style and tough political bargaining. Using equal parts moral leverage, the memory of the slain JFK, and his own brand of hardball politics, Johnson overcame the filibuster. In June 1964, Congress approved the most far-reaching civil rights law since Reconstruction. The keystone of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, outlawed discrimination in employment on the basis of race, religion, national origin, and sex. Another section guaranteed equal access to public accommodations and schools. The law granted new enforcement powers to the U.S. attorney general and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to implement the prohibition against job discrimination.

Freedom Summer The Civil Rights Act was a law with real teeth, but it left untouched the obstacles to black voting rights. So protesters went back into the streets. In 1964, in what came to be known as Freedom Summer, black organizations mounted a major campaign in Mississippi. The effort drew several thousand volunteers from across the country, including nearly one thousand white college students from the North. Led by the charismatic SNCC activist Robert Moses, the four major civil rights organizations (SNCC, CORE, NAACP, and SCLC) spread out across the state. They established freedom schools for black children and conducted a major voter registration drive. Yet so determined was the opposition that only about twelve hundred black voters were registered that summer, at a cost of four murdered civil rights workers and thirty-seven black churches bombed or burned.

The murders strengthened the resolve of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which had been founded during Freedom Summer. Banned from the “whites only” Mississippi Democratic Party, MFDP leaders were determined to attend the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, as the legitimate representatives of their state. Inspired by Fannie Lou Hamer, a former sharecropper turned civil rights activist, the MFDP challenged the most powerful figures in the Democratic Party, including Lyndon Johnson, the Democrats’ presidential nominee. “Is this America?” Hamer asked party officials when she demanded that the MFDP, and not the all-white Mississippi delegation, be recognized by the convention. Democratic leaders, however, seated the white Mississippi delegation and refused to recognize the MFDP. Demoralized and convinced that the Democratic Party would not change, Moses told television reporters: “I will have nothing to do with the political system any longer.”

Selma and the Voting Rights Act Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC did not share Moses’s skepticism. They believed that another confrontation with southern injustice could provoke further congressional action. In March 1965, James Bevel of the SCLC called for a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital, Montgomery, to protest the murder of a voting-rights activist. As soon as the six hundred marchers left Selma, crossing over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, mounted state troopers attacked them with tear gas and clubs. The scene was shown on national television that night, and the day became known as Bloody Sunday. Calling the episode “an American tragedy,” President Johnson went back to Congress.

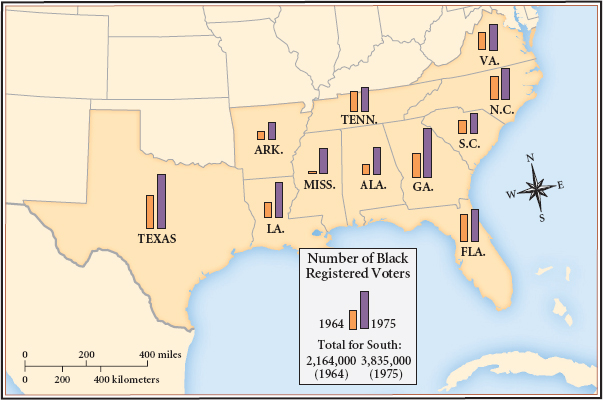

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was signed by President Johnson on August 6, outlawed the literacy tests and other devices that prevented African Americans from registering to vote, and authorized the attorney general to send federal examiners to register voters in any county where registration was less than 50 percent. Together with the Twenty-fourth Amendment (1964), which outlawed the poll tax in federal elections, the Voting Rights Act enabled millions of African Americans to vote for the first time since the Reconstruction era.

In the South, the results were stunning. In 1960, only 20 percent of black citizens had been registered to vote; by 1971, registration reached 62 percent (Map 27.4). Moreover, across the nation the number of black elected officials began to climb, quadrupling from 1,400 to 4,900 between 1970 and 1980 and doubling again by the early 1990s. Most of those elected held local offices — from sheriff to county commissioner — but nonetheless embodied a shift in political representation nearly unimaginable a generation earlier. As Hartman Turnbow, a Mississippi farmer who risked his life to register in 1964, later declared, “It won’t never go back where it was.”

Something else would never go back either: the liberal New Deal coalition. By the second half of the 1960s, the liberal wing of the Democratic Party had won its battle with the conservative, segregationist wing. Democrats had embraced the civil rights movement and made African American equality a cornerstone of a new “rights” liberalism. But over the next generation, between the 1960s and the 1980s, southern whites and many conservative northern whites would respond by switching to the Republican Party. Strom Thurmond, the segregationist senator from South Carolina, symbolically led the revolt by renouncing the Democrats and becoming a Republican in 1964. The New Deal coalition — which had joined working-class whites, northern African Americans, urban professionals, and white southern segregationists together in a fragile political alliance since the 1930s — was beginning to crumble.

TRACE CHANGE OVER TIME