World War II: The Beginnings

During the war fought “to make the world safe for democracy,” the United States was far from ready to extend full equality to its own black citizens. Black workers faced discrimination in wartime employment, and the more than one million black troops who served in World War II were placed in segregated units commanded by whites. Both at home and abroad, World War II “immeasurably magnified the Negro’s awareness of the disparity between the American profession and practice of democracy,” NAACP president Walter White observed.

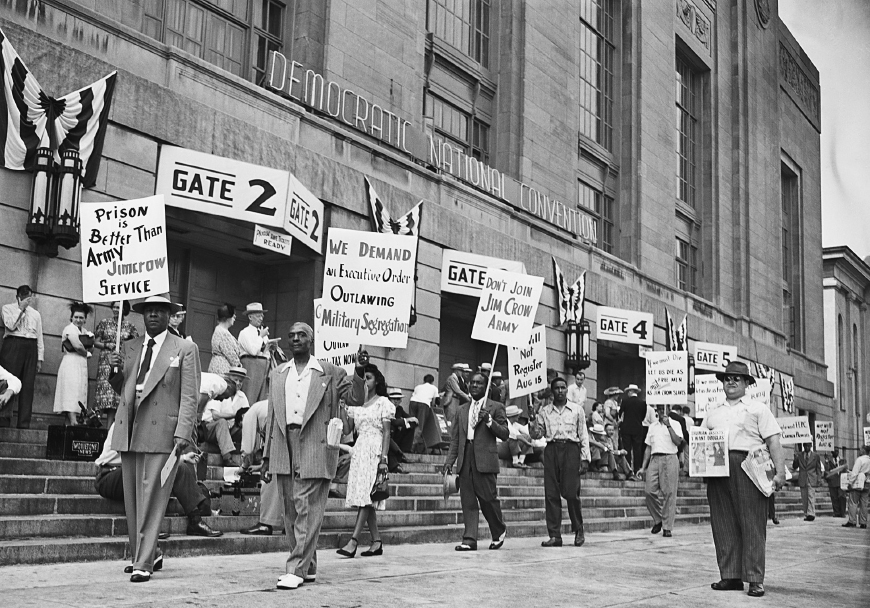

Executive Order 8802 On the home front, activists pushed two strategies. First, A. Philip Randolph, whose Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was the most prominent black trade union, called for a march on Washington in early 1941. Randolph planned to bring 100,000 protesters to the nation’s capital if African Americans were not given equal opportunity in war jobs — then just beginning to expand with President Franklin Roosevelt’s pledge to supply the Allies with materiel. To avoid a divisive protest, FDR issued Executive Order 8802 in June of that year, prohibiting racial discrimination in defense industries, and Randolph agreed to cancel the march. The resulting Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) had few enforcement powers, but it set an important precedent: federal action. Randolph’s efforts showed that white leaders and institutions could be swayed by concerted African American action. It would be a critical lesson for the movement.

The Double V Campaign A second strategy jumped from the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the foremost African American newspapers of the era. It was the brainchild of an ordinary cafeteria worker from Kansas. In a 1942 letter to the editor, James G. Thompson urged that “colored Americans adopt the double VV for a double victory” — victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home. Edgar Rouzeau, editor of the paper’s New York office, agreed: “Black America must fight two wars and win in both.” Instantly dubbed the Double V Campaign, Thompson’s notion, with Rouzeau’s backing, spread like wildfire through black communities across the country. African Americans would demonstrate their loyalty and citizenship by fighting the Axis powers. But they would also demand, peacefully but emphatically, the defeat of racism at home. “The suffering and privation may be great,” Rouzeau told his readers, “but the rewards loom even greater.”

The Double V efforts met considerable resistance. In war industries, factories periodically shut down in Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and other cities because of “hate strikes”: the refusal of white workers to labor alongside black workers. Detroit was especially tense. Referring to the potential for racial strife, Life magazine reported in 1942 that “Detroit is Dynamite. … It can either blow up Hitler or blow up America.” In 1943, it nearly did the latter. On a hot summer day, whites from the city’s ethnic neighborhoods taunted and beat African Americans in a local park. Three days of rioting ensued in which thirty-four people were killed, twenty-five of them black. Federal troops were called in to restore order.

Despite and because of such incidents, a generation was spurred into action during the war years. In New York City, employment discrimination on the city’s transit lines prompted one of the first bus boycotts in the nation’s history, led in 1941 by Harlem minister Adam Clayton Powell Jr. In Chicago, James Farmer and three other members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a nonviolent peace organization, founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942. FOR and CORE adopted the philosophy of nonviolent direct action espoused by Mahatma Gandhi of India. Another FOR member in New York, Bayard Rustin, was equally instrumental in promoting direct action; he led one of the earliest challenges to southern segregation, the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation. Meanwhile, after the war, hundreds of thousands of African American veterans used the GI Bill to go to college, trade school, or graduate school, placing themselves in a position to push against segregation. At the war’s end, Powell affirmed that “the black man … is ready to throw himself into the struggle to make the dream of America become flesh and blood, bread and butter.”

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES