The Antiwar Movement and the 1968 Election

Before their deaths, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had spoken eloquently against the Vietnam War. To antiwar activists, however, bold speeches and marches had not produced the desired effect. “We are no longer interested in merely protesting the war,” declared one. “We are out to stop it.” They sought nothing short of an immediate American withdrawal. Their anger at Johnson and the Democratic Party — fueled by news of the Tet offensive, the murders of King and Kennedy, and the general youth rebellion — had radicalized the movement.

Democratic Convention In August, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the political divisions generated by the war consumed the party. Thousands of protesters descended on the city. The most visible group, led by Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, a remarkable pair of troublemakers, claimed to represent the Youth International Party. To mock those inside the convention hall, these “Yippies” nominated a pig, Pigasus, for president. The Yippies’ stunts were geared toward maximum media exposure. But a far larger and more serious group of activists had come to Chicago to demonstrate against the war as well — and they staged what many came to call the Siege of Chicago.

Democratic mayor Richard J. Daley ordered the police to break up the demonstrations. Several nights of skirmishes between protesters and police culminated on the evening of the nominations. In what an official report later described as a “police riot,” police officers attacked protesters with tear gas and clubs. As the nominating speeches proceeded, television networks broadcast scenes of the riot, cementing a popular impression of the Democrats as the party of disorder. “They are going to be spending the next four years picking up the pieces,” one Republican said gleefully. Inside the hall, the party dispiritedly nominated Hubert H. Humphrey, Johnson’s vice president. The delegates approved a middle-of-the-road platform that endorsed continued fighting in Vietnam while urging a diplomatic solution to the conflict.

Richard Nixon On the Republican side, Richard Nixon had engineered a remarkable political comeback. After losing the presidential campaign in 1960 and the California gubernatorial race in 1962, he won the Republican presidential nomination in 1968. Sensing Democratic weakness, Nixon and his advisors believed there were two groups of voters ready to switch sides: northern working-class voters and southern whites.

Tired of the antiwar movement, the counterculture, and urban riots, northern blue-collar voters, especially Catholics, had drifted away from the Democratic Party. Growing up in the Great Depression, these families were admirers of FDR and perhaps even had his picture on their living-room wall. But times had changed over three decades. To show how much they had changed, the social scientists Ben J. Wattenberg and Richard Scammon profiled blue-collar workers in their study The Real Majority (1970). Wattenberg and Scammon asked their readers to consider people such as a forty-seven-year-old machinist’s wife from Dayton, Ohio: “[She] is afraid to walk the streets alone at night. … She has a mixed view about blacks and civil rights.” Moreover, they wrote, “she is deeply distressed that her son is going to a community junior college where LSD was found on campus.” Such northern blue-collar families were once reliable Democratic voters, but their political loyalties were increasingly up for grabs — a fact Republicans knew well.

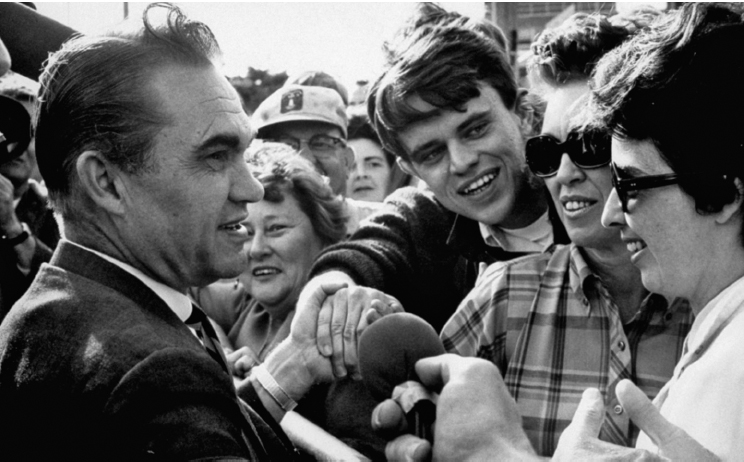

George Wallace Working-class anxieties over student protests and urban riots were first exploited by the controversial governor of Alabama, George C. Wallace. Running in 1968 as a third-party presidential candidate, Wallace traded on his fame as a segregationist governor. He had tried to stop the federal government from desegregating the University of Alabama in 1963, and he was equally obstructive during the Selma crisis of 1965. Appealing to whites in both the North and the South, Wallace called for “law and order” and claimed that mothers on public assistance were, thanks to Johnson’s Great Society, “breeding children as a cash crop.”

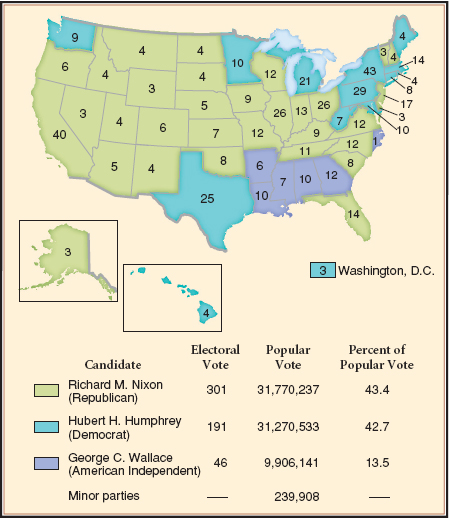

Wallace’s hope was that by carrying the South, he could deny a major candidate an electoral majority and force the election into the House of Representatives. That strategy failed, as Wallace finished with just 13.5 percent of the popular vote. But he had defined hot-button issues — liberal elitism, welfare policies, and law and order — that became hallmarks for the next generation of mainstream conservatives.

Nixon’s Strategy Nixon offered a subtler version of Wallace’s populism in a two-pronged approach to the campaign. He adopted what his advisors called the “southern strategy,” which aimed at attracting southern white voters still smarting over the civil rights gains by African Americans. Nixon won over the key southerner, Democrat-turned-Republican senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, the 1948 Dixiecrat presidential nominee. Nixon informed Thurmond that while formally he had to support civil rights, his administration would go easy on enforcement. He also campaigned against the antiwar movement, urban riots, and protests, calling for a strict adherence to “law and order.” He pledged to represent the “quiet voice” of the “great majority of Americans, the forgotten Americans, the nonshouters, the nondemonstrators.” Here Nixon was speaking not just to the South, but to the many millions of suburban voters across the country who worried that social disorder had gripped the nation.

These strategies — southern and suburban — worked. Nixon received 43.4 percent of the vote to Humphrey’s 42.7 percent, defeating him by a scant 500,000 votes out of the 73 million that were cast (Map 28.3). But the numerical closeness of the race could not disguise the devastating blow to the Democrats. Humphrey received almost 12 million fewer votes than Johnson had in 1964. The white South largely abandoned the Democratic Party, an exodus that would accelerate in the 1970s. In the North, Nixon and Wallace made significant inroads among traditionally Democratic voters. New Deal Democrats lost the unity of purpose that had served them for thirty years. A nation exhausted by months of turmoil and violence had chosen a new direction. Nixon’s victory in 1968 foreshadowed — and helped propel — a national electoral realignment in the coming decade.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW