The 1972 Election

Political realignments have been infrequent in American history. One occurred between 1932 and 1936, when many Republicans, despairing over the Great Depression, had switched sides and voted for FDR. The years between 1968 and 1972 were another such pivotal moment. This time, Democrats were the ones who abandoned their party.

After the 1968 elections, the Democrats fell into disarray. Bent on sweeping away the party’s old guard, reformers took over, adopting new rules that granted women, African Americans, and young people delegate seats “in reasonable relation to their presence in the population.” In the past, an alliance of urban machines, labor unions, and white ethnic groups — the heart of the New Deal coalition — dominated the nominating process. But at the 1972 convention, few of the party faithful qualified as delegates under the changed rules. The crowning insult came when the convention rejected the credentials of Chicago mayor Richard Daley and his delegation, seating instead an Illinois delegation led by Jesse Jackson, a firebrand young black minister and former aide to Martin Luther King Jr.

Capturing the party was one thing; beating the Republicans was quite another. These party reforms opened the door for George McGovern, a liberal South Dakota senator and favorite of the antiwar and women’s movements, to capture the nomination. But McGovern took a number of missteps, including failing to mollify key party backers such as the AFL-CIO, which, for the first time in memory, refused to endorse the Democratic ticket. A weak campaigner, McGovern was also no match for Nixon, who pulled out all the stops. Using the advantages of incumbency, Nixon gave the economy a well-timed lift and proclaimed (prematurely) a cease-fire in Vietnam. Nixon’s appeal to the “silent majority” — people who “care about a strong United States, about patriotism, about moral and spiritual values” — was by now well honed.

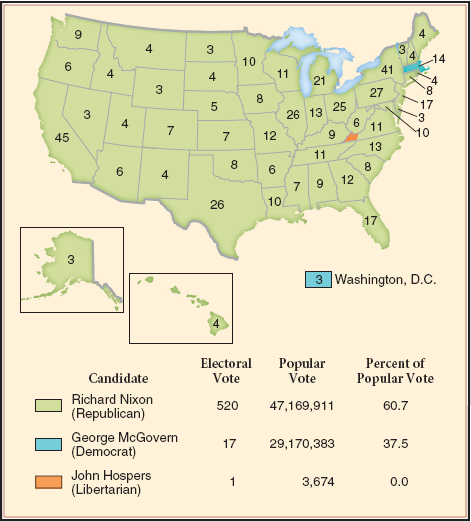

Nixon won in a landslide, receiving nearly 61 percent of the popular vote and carrying every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia (Map 28.4). The returns revealed how fractured traditional Democratic voting blocs had become. McGovern received only 38 percent of the big-city Catholic vote and lost 42 percent of self-identified Democrats overall. The 1972 election marked a pivotal moment in the country’s shift to the right. Yet observers legitimately wondered whether the 1972 election results proved the popularity of conservatism or merely showed that the country had grown weary of liberalism and the changes it had wrought in national life.