Energy Crisis

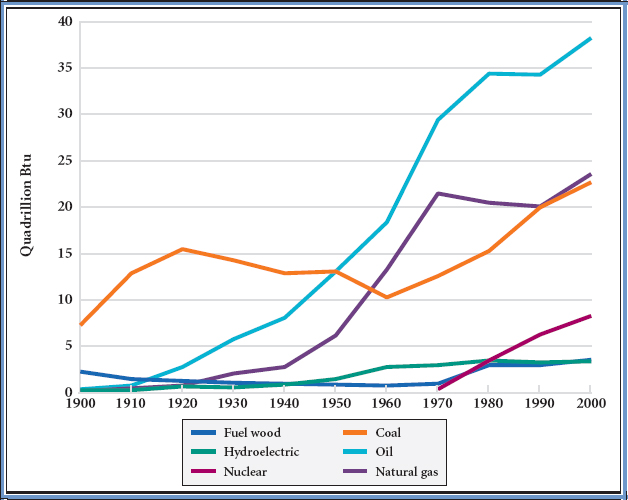

Modern economies run on oil. If the oil supply is drastically reduced, woe follows. Something like that happened to the United States in the 1970s. Once the world’s leading oil producer, the United States had become heavily dependent on inexpensive imported oil, mostly from the Persian Gulf (Figure 29.1). American and European oil companies had discovered and developed the Middle Eastern fields early in the twentieth century, when much of the region was ruled by the British and French empires. When Middle Eastern states threw off the remnants of European colonialism, they demanded concessions for access to the fields. Foreign companies still extracted the oil, but now they did so under profit-sharing agreements with the Persian Gulf states. In 1960, these nations and other oil-rich developing countries formed a cartel (a business association formed to control prices), the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Conflict between Israel and the neighboring Arab states of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan prompted OPEC to take political sides between 1967 and 1973. Following Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, Israeli-Arab tensions in the region grew closer to boiling over with each passing year. In the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Egypt and Syria invaded Israel to regain territory lost in the 1967 conflict. Israel prevailed, but only after being resupplied by an emergency American airlift. In response to U.S. support for Israel, the Arab states in OPEC declared an oil embargo in October 1973. Gas prices in the United States quickly jumped by 40 percent and heating oil prices by 30 percent. Demand outpaced supply, and Americans found themselves parked for hours in mile-long lines at gasoline stations for much of the winter of 1973–1974. Oil had become a political weapon, and the West’s vulnerability stood revealed.

The United States scrambled to meet its energy needs in the face of the oil shortage. Just two months after the OPEC embargo began, Congress imposed a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour to conserve fuel. Americans began to buy smaller, more fuel-efficient cars such as Volkswagens, Toyotas, and Datsuns (later Nissans) — while sales of Detroit-made cars (now nicknamed “gas guzzlers”) slumped. With one of every six jobs in the country generated directly or indirectly by the auto industry, the effects rippled across the economy. Compounding the distress was the raging inflation set off by the oil shortage; prices of basic necessities, such as bread, milk, and canned goods, rose by nearly 20 percent in 1974 alone. “THINGS WILL GET WORSE,” one newspaper headline warned, “BEFORE THEY GET WORSE.”