England’s Tobacco Colonies

England was slow to embrace the prospect of planting colonies in the Americas. There were fumbling attempts in the 1580s in Newfoundland and Maine, privately organized and poorly funded. Sir Walter Raleigh’s three expeditions to North Carolina likewise ended in disaster when 117 settlers on Roanoke Island, left unsupplied for several years, vanished. The fate of Roanoke — the “lost colony” — remains a compelling puzzle for modern historians.

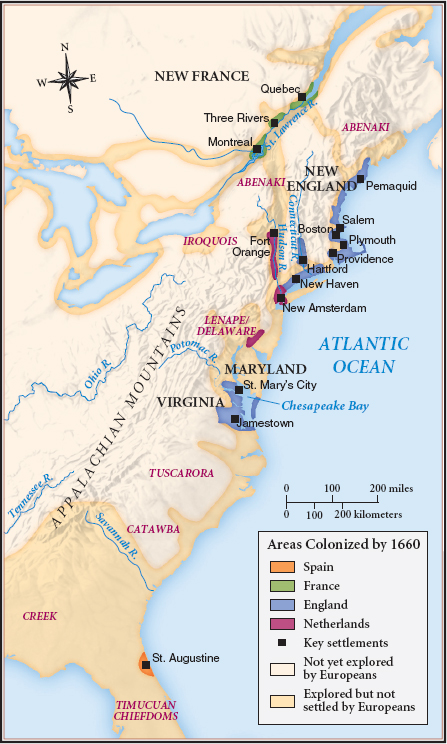

The Jamestown Settlement Merchants then took charge of English expansion. In 1606, King James I (r. 1603–1625) granted to the Virginia Company of London all the lands stretching from present-day North Carolina to southern New York. To honor the memory of Elizabeth I, the never-married “Virgin Queen,” the company’s directors named the region Virginia (Map 2.3). Influenced by the Spanish example, in 1607 the Virginia Company dispatched an all-male group with no ability to support itself — no women, farmers, or ministers were among the first arrivals — that expected to extract tribute from the region’s Indian population while it searched out valuable commodities like pearls and gold. Some were young gentlemen with personal ties to the company’s shareholders: a bunch of “unruly Sparks, packed off by their Friends to escape worse Destinies at home.” Others hoped to make a quick profit. All they wanted, one of them said, was to “dig gold, refine gold, load gold.”

But there was no gold, and the men fared poorly in their new environment. Arriving in Virginia after an exhausting four-month voyage, they settled on a swampy peninsula, which they named Jamestown to honor the king. There the adventurers lacked access to fresh water, refused to plant crops, and quickly died off; only 38 of the 120 men were alive nine months later. Death rates remained high: by 1611, the Virginia Company had dispatched 1,200 colonists to Jamestown, but fewer than half remained alive. “Our men were destroyed with cruell diseases, as Swellings, Fluxes, Burning Fevers, and by warres,” reported one of the settlement’s leaders, “but for the most part they died of meere famine.”

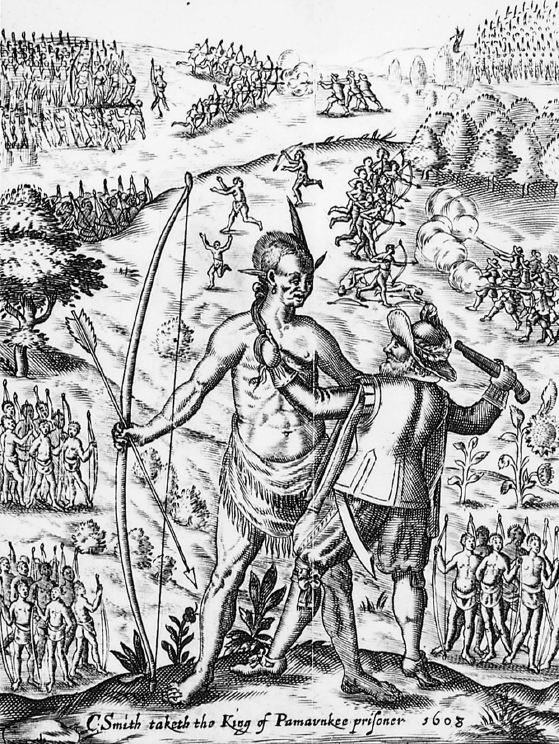

Their plan to dominate the local Indian population ran up against the presence of Powhatan, the powerful chief who oversaw some thirty tribal chiefdoms between the James and Potomac rivers. He was willing to treat the English traders as potential allies who could provide valuable goods, but — just as the Englishmen expected tribute from the Indians — Powhatan expected tribute from the English. He provided the hungry English adventurers with corn; in return, he demanded “hatchets … bells, beads, and copper” as well as “two great guns” and expected Jamestown to become a dependent community within his chiefdom. Subsequently, Powhatan arranged a marriage between his daughter Pocahontas and John Rolfe, an English colonist (Thinking Like a Historian). But these tactics failed. The inability to decide who would pay tribute to whom led to more than a decade of uneasy relations, followed by a long era of ruinous warfare.

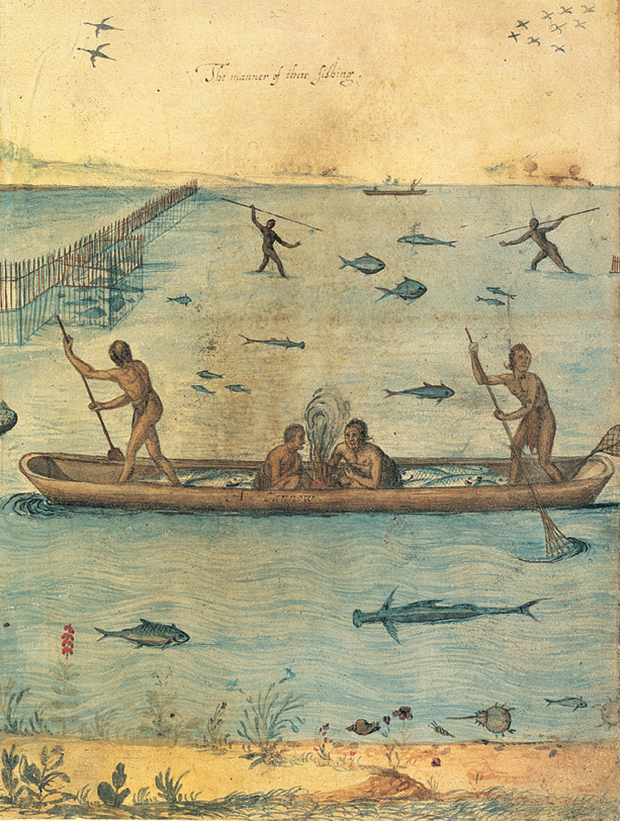

The war was precipitated by the discovery of a cash crop that — like sugar in Brazil — offered colonists a way to turn a profit but required steady expansion onto Indian lands. Tobacco was a plant native to the Americas, long used by Indians as a medicine and a stimulant. John Rolfe found a West Indian strain that could flourish in Virginia soil and produced a small crop — “pleasant, sweet, and strong” — that fetched a high price in England and spurred the migration of thousands of new settlers. The English soon came to crave the nicotine that tobacco contained. James I initially condemned the plant as a “vile Weed” whose “black stinking fumes” were “baleful to the nose, harmful to the brain, and dangerous to the lungs.” But the king’s attitude changed as taxes on imported tobacco bolstered the royal treasury. Powhatan, however, now accused the English of coming “not to trade but to invade my people and possess my country.”

To foster the flow of migrants, the Virginia Company allowed individual settlers to own land, granting 100 acres to every freeman and more to those who imported servants. The company also created a system of representative government: the House of Burgesses, first convened in 1619, could make laws and levy taxes, although the governor and the company council in England could veto its acts. By 1622, landownership, self-government, and a judicial system based on “the lawes of the realme of England” had attracted some 4,500 new recruits. To encourage the transition to a settler colony, the Virginia Company recruited dozens of “Maides young and uncorrupt to make wifes to the Inhabitants.”

The Indian War of 1622 The influx of migrants sparked an all-out conflict with the neighboring Indians. The struggle began with an assault led by Opechancanough, Powhatan’s younger brother and successor. In 1607, Opechancanough had attacked some of the first English invaders; subsequently, he “stood aloof” from the English settlers and “would not be drawn to any Treaty.” In particular, he resisted English proposals to place Indian children in schools to be “brought upp in Christianytie.” Upon becoming the paramount chief in 1621, Opechancanough told the leader of the neighboring Potomack Indians: “Before the end of two moons, there should not be an Englishman in all their Countries.”

Opechancanough almost succeeded. In 1622, he coordinated a surprise attack by twelve Indian chiefdoms that killed 347 English settlers, nearly one-third of the population. The English fought back by seizing the fields and food of those they now called “naked, tanned, deformed Savages” and declared “a perpetual war without peace or truce” that lasted for a decade. They sold captured warriors into slavery, “destroy[ing] them who sought to destroy us” and taking control of “their cultivated places.”

Shocked by the Indian uprising, James I revoked the Virginia Company’s charter and, in 1624, made Virginia a royal colony. Now the king and his ministers appointed the governor and a small advisory council, retaining the locally elected House of Burgesses but stipulating that the king’s Privy Council (a committee of political advisors) must ratify all legislation. The king also decreed the legal establishment of the Church of England in the colony, which meant that residents had to pay taxes to support its clergy. These institutions — an appointed governor, an elected assembly, a formal legal system, and an established Anglican Church — became the model for royal colonies throughout English America.

Lord Baltimore Settles Catholics in Maryland A second tobacco-growing colony developed in neighboring Maryland. King Charles I (r. 1625–1649), James’s successor, was secretly sympathetic toward Catholicism, and in 1632 he granted lands bordering the vast Chesapeake Bay to Catholic aristocrat Cecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore. Thus Maryland became a refuge for Catholics, who were subject to persecution in England. In 1634, twenty gentlemen, mostly Catholics, and 200 artisans and laborers, mostly Protestants, established St. Mary’s City at the mouth of the Potomac River. To minimize religious confrontations, the proprietor instructed the governor to allow “no scandall nor offence to be given to any of the Protestants” and to “cause All Acts of Romane Catholicque Religion to be done as privately as may be.”

Maryland grew quickly because Baltimore imported many artisans and offered ample lands to wealthy migrants. But political conflict threatened the colony’s stability. Disputing Baltimore’s powers, settlers elected a representative assembly and insisted on the right to initiate legislation, which Baltimore grudgingly granted. Anti-Catholic agitation by Protestants also threatened his religious goals. To protect his coreligionists, Lord Baltimore persuaded the assembly to enact the Toleration Act (1649), which granted all Christians the right to follow their beliefs and hold church services. In Maryland, as in Virginia, tobacco quickly became the main crop, and that similarity, rather than any religious difference, ultimately made the two colonies very much alike in their economic and social systems.

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES