From Mercantilism to Imperial Dominion

As Charles II distributed American land, his ministers devised policies to keep colonial trade in English hands. Since the 1560s, the English crown had pursued mercantilist policies, using government subsidies and charters to stimulate English manufacturing and foreign trade. Now it extended these mercantilist strategies to the American settlements through the Navigation Acts (Table 3.2).

| Navigation Acts, 1651–1751 | ||

| Purpose | Compliance | |

| Act of 1651 | Cut Dutch trade | Mostly ignored |

| Act of 1660 | Ban foreign shipping; enumerate goods that go only to England | Partially obeyed |

| Act of 1663 | Allow European imports only through England | Partially obeyed |

| Staple Act (1673) | Ensure enumerated goods go only to England | Mostly obeyed |

| Act of 1696 | Prevent frauds; create vice-admiralty courts | Mostly obeyed |

| Woolen Act (1699) | Prevent export or intercolonial sale of textiles | Partially obeyed |

| Hat Act (1732) | Prevent export or intercolonial sale of hats | Partially obeyed |

| Molasses Act (1733) | Cut American imports of molasses from French West Indies | Extensively violated |

| Iron Act (1750) | Prevent manufacture of finished iron products | Extensively violated |

| Currency Act (1751) | End use of paper currency as legal tender in New England | Mostly obeyed |

The Navigation Acts Believing they had to control trade with the colonies to reap their economic benefits, English ministers wanted agricultural goods and raw materials to be carried to English ports in English vessels. In reality, Dutch and French shippers were often buying sugar and other colonial products from English colonies and carrying them directly into foreign markets. To counter this practice, the Navigation Act of 1651 required that goods be carried on ships owned by English or colonial merchants. New parliamentary acts in 1660 and 1663 strengthened the ban on foreign traders: colonists could export sugar and tobacco only to England and import European goods only through England; moreover, three-quarters of the crew on English vessels had to be English. To pay the customs officials who enforced these laws, the Revenue Act of 1673 imposed a “plantation duty” on American exports of sugar and tobacco.

The English government backed these policies with military force. In three wars between 1652 and 1674, the English navy drove the Dutch from New Netherland and contested Holland’s control of the Atlantic slave trade by attacking Dutch forts and ships along the West African coast. Meanwhile, English merchants expanded their fleets, which increased in capacity from 150,000 tons in 1640 to 340,000 tons in 1690. This growth occurred on both sides of the Atlantic; by 1702, only London and Bristol had more ships registered in port than did the town of Boston.

Though colonial ports benefitted from the growth of English shipping, many colonists violated the Navigation Acts. Planters continued to trade with Dutch shippers, and New England merchants imported sugar and molasses from the French West Indies. The Massachusetts Bay assembly boldly declared: “The laws of England are bounded within the seas [surrounding it] and do not reach America.” Outraged by this insolence, customs official Edward Randolph called for troops to “reduce Massachusetts to obedience.” Instead, the Lords of Trade — the administrative body charged with colonial affairs — chose a less violent, but no less confrontational, strategy. In 1679, it denied the claim of Massachusetts Bay to New Hampshire and eventually established a separate royal colony there. Then, in 1684, the Lords of Trade persuaded an English court to annul the Massachusetts Bay charter by charging the Puritan government with violating the Navigation Acts and virtually outlawing the Church of England.

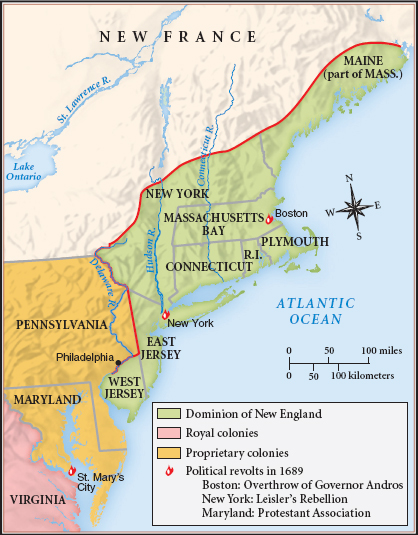

The Dominion of New England The Puritans’ troubles had only begun, thanks to the accession of King James II (r. 1685–1688), an aggressive and inflexible ruler. During the reign of Oliver Cromwell, James had grown up in exile in France, and he admired its authoritarian king, Louis XIV. James wanted stricter control over the colonies and targeted New England for his reforms. In 1686, the Lords of Trade revoked the charters of Connecticut and Rhode Island and merged them with Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth to form a new royal province, the Dominion of New England. As governor of the Dominion, James II appointed Sir Edmund Andros, a hard-edged former military officer. Two years later, James II added New York and New Jersey to the Dominion, creating a vast colony that stretched from Maine to Pennsylvania (Map 3.1).

The Dominion extended to America the authoritarian model of colonial rule that the English government had imposed on Catholic Ireland. James II ordered Governor Andros to abolish the existing legislative assemblies. In Massachusetts, Andros banned town meetings, angering villagers who prized local self-rule, and advocated public worship in the Church of England, offending Puritan Congregationalists. Even worse, from the colonists’ perspective, the governor invalidated all land titles granted under the original Massachusetts Bay charter. Andros offered to provide new deeds, but only if the colonists would pay an annual fee.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT