Religion and Politics

In Western Europe, the leaders of church and state condemned religious diversity. “To tolerate all [religions] without controul is the way to have none at all,” declared an Anglican clergyman. Orthodox church officials carried such sentiments to Pennsylvania. “The preachers do not have the power to punish anyone, or to force anyone to go to church,” complained Gottlieb Mittelberger, an influential German minister. As a result, “Sunday is very badly kept. Many people plough, reap, thresh, hew or split wood and the like.” He concluded: “Liberty in Pennsylvania does more harm than good to many people, both in soul and body.”

Mittelberger was mistaken. Although ministers in Pennsylvania could not invoke government authority to uphold religious values, the result was not social anarchy. Instead, religious sects enforced moral behavior through communal self-discipline. Quaker families attended a weekly meeting for worship and a monthly meeting for business; every three months, a committee reminded parents to provide proper religious instruction. The committee also supervised adult behavior; a Chester County meeting, for example, disciplined a member “to reclaim him from drinking to excess and keeping vain company.” Significantly, Quaker meetings allowed couples to marry only if they had land and livestock sufficient to support a family. As a result, the children of well-to-do Friends usually married within the sect, while poor Quakers remained unmarried, wed later in life, or married without permission — in which case they were often ousted from the meeting. These marriage rules helped the Quakers build a self-contained and prosperous community.

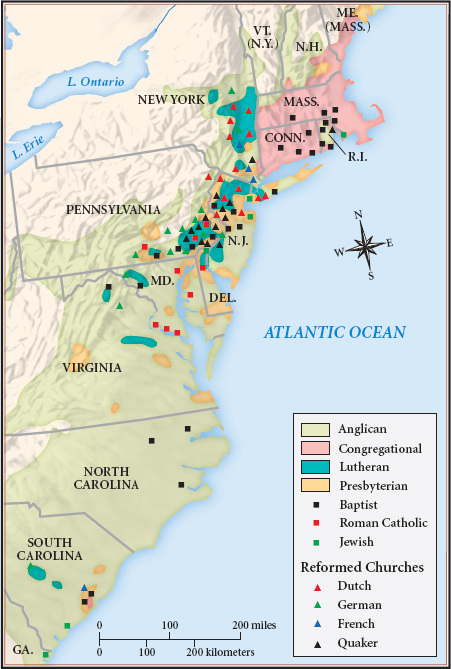

In the 1740s, the flood of new migrants reduced Quakers to a minority — a mere 30 percent of Pennsylvanians. Moreover, Scots-Irish settlers in central Pennsylvania demanded an aggressive Indian policy, challenging the pacifism of the assembly. To retain power, Quaker politicians sought an alliance with those German religious groups that also embraced pacifism and voluntary (not compulsory) militia service. In response, German leaders demanded more seats in the assembly and laws that respected their inheritance customs. Other Germans — Lutherans and Baptists — tried to gain control of the assembly by forming a “general confederacy” with Scots-Irish Presbyterians. An observer predicted that the scheme was doomed to failure because of “mutual jealousy” (Map 4.3).

By the 1750s, politics throughout the Middle colonies roiled with conflict. In New York, a Dutchman declared that he “Valued English Law no more than a Turd,” while in Pennsylvania, Benjamin Franklin disparaged the “boorish” character and “swarthy complexion” of German migrants. Yet there was broad agreement on the importance of economic opportunity and liberty of conscience. The unstable balance between shared values and mutual mistrust prefigured tensions that would pervade an increasingly diverse American society in the centuries to come.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW