The Enlightenment in America

To explain the workings of the natural world, some colonists relied on folk wisdom. Swedish migrants in Pennsylvania attributed magical powers to the great white mullein, a common wildflower, and treated fevers by tying the plant’s leaves around their feet and arms. Traditionally, Christians believed that the earth stood at the center of the universe, and God (and Satan) intervened directly and continuously in human affairs. The scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries challenged these ideas, and educated people — most of them Christians — began to modify their views accordingly.

The European Enlightenment In 1543, the Polish astronomer Copernicus published his observation that the earth traveled around the sun, not vice versa. Copernicus’s discovery suggested that humans occupied a more modest place in the universe than Christian theology assumed. In the next century, Isaac Newton, in his Principia Mathematica (1687), used the sciences of mathematics and physics to explain the movement of the planets around the sun (and invented calculus in the process). Though Newton was himself profoundly religious, in the long run his work undermined the traditional Christian understanding of the cosmos.

In the century between the Principia Mathematica and the French Revolution of 1789, the philosophers of the European Enlightenment used empirical research and scientific reasoning to study all aspects of life, including social institutions and human behavior. Enlightenment thinkers advanced four fundamental principles: the lawlike order of the natural world, the power of human reason, the “natural rights” of individuals (including the right to self-government), and the progressive improvement of society.

English philosopher John Locke was a major contributor to the Enlightenment. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Locke stressed the impact of environment and experience on human behavior and beliefs, arguing that the character of individuals and societies was not fixed but could be changed through education, rational thought, and purposeful action. Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1690) advanced the revolutionary theory that political authority was not given by God to monarchs, as James II had insisted (see Chapter 3). Instead, it derived from social compacts that people made to preserve their natural rights to life, liberty, and property. In Locke’s view, the people should have the power to change government policies — or even their form of government.

Some clergymen responded to these developments by devising a rational form of Christianity. Rejecting supernatural interventions and a vengeful Calvinist God, Congregationalist minister Andrew Eliot maintained that “there is nothing in Christianity that is contrary to reason.” The Reverend John Wise of Ipswich, Massachusetts, used Locke’s philosophy to defend giving power to ordinary church members. Just as the social compact formed the basis of political society, Wise argued, so the religious covenant among the lay members of a congregation made them — not the bishops of the Church of England or even ministers like himself — the proper interpreters of religious truth. The Enlightenment influenced Puritan minister Cotton Mather as well. When a measles epidemic ravaged Boston in the 1710s, Mather thought that only God could end it; but when smallpox struck a decade later, he used his newly acquired knowledge of inoculation — gained in part from a slave, who told him of the practice’s success in Africa — to advocate this scientific preventive for the disease.

Franklin’s Contributions Benjamin Franklin was the exemplar of the American Enlightenment. Born in Boston in 1706 to devout Calvinists, he grew to manhood during the print revolution. Apprenticed to his brother, a Boston printer, Franklin educated himself through voracious reading. At seventeen, he fled to Philadelphia, where he became a prominent printer, and in 1729 he founded the Pennsylvania Gazette, which became one of the colonies’ most influential newspapers. Franklin also formed a “club of mutual improvement” that met weekly to discuss “Morals, Politics, or Natural Philosophy.” These discussions, as well as Enlightenment literature, shaped his thinking. As Franklin explained in his Autobiography (1771), “From the different books I read, I began to doubt of Revelation [God-revealed truth].”

Like a small number of urban artisans, wealthy Virginia planters, and affluent seaport merchants, Franklin became a deist. Deism was a way of thinking, not an established religion. “My own mind is my own church,” said deist Thomas Paine. “I am of a sect by myself,” added Thomas Jefferson. Influenced by Enlightenment science, deists such as Jefferson believed that a Supreme Being (or Grand Architect) created the world and then allowed it to operate by natural laws but did not intervene in people’s lives. Rejecting the divinity of Christ and the authority of the Bible, deists relied on “natural reason,” their innate moral sense, to define right and wrong. Thus Franklin, a onetime slave owner, came to question the morality of slavery, repudiating it once he recognized the parallels between racial bondage and the colonies’ political bondage to Britain.

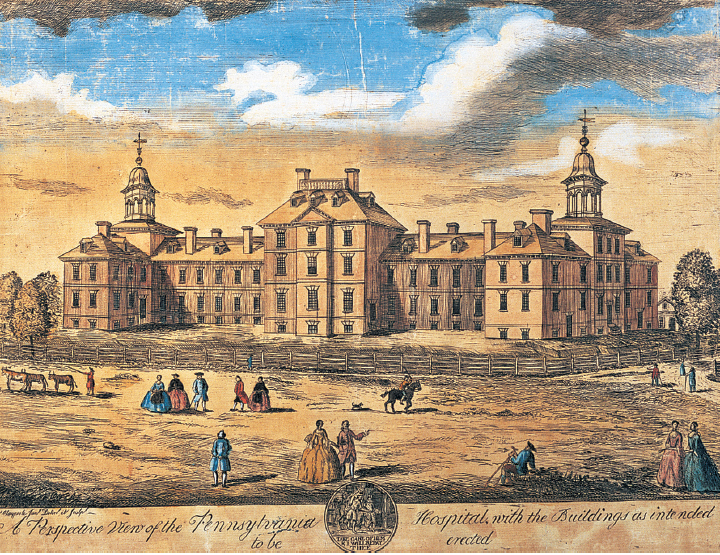

Franklin popularized the practical outlook of the Enlightenment in Poor Richard’s Almanack (1732–1757), an annual publication that was read by thousands. He also founded the American Philosophical Society (1743–present) to promote “useful knowledge.” Adopting this goal in his own life, Franklin invented bifocal lenses for eyeglasses, the Franklin stove, and the lightning rod. His book on electricity, published in England in 1751, won praise as the greatest contribution to science since Newton’s discoveries. Inspired by Franklin, ambitious printers in America’s seaport cities published newspapers and gentlemen’s magazines, the first significant nonreligious periodicals to appear in the colonies. The European Enlightenment, then, added a secular dimension to colonial cultural life, foreshadowing the great contributions to republican political theory by American intellectuals of the Revolutionary era: John Adams, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson.

PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT