The Federalist Legacy

The War of 1812 ushered in a new phase of the Republican political revolution. Before the conflict, Federalists had strongly supported Alexander Hamilton’s program of national mercantilism — a funded debt, a central bank, and tariffs — while Jeffersonian Republicans had opposed it. After the war, the Republicans split into two camps. Led by Henry Clay, National Republicans pursued Federalist-like policies. In 1816, Clay pushed legislation through Congress creating the Second Bank of the United States and persuaded President Madison to sign it. In 1817, Clay won passage of the Bonus Bill, which created a national fund for roads and other internal improvements. Madison vetoed it. Reaffirming traditional Jeffersonian Republican principles, he argued that the national government lacked the constitutional authority to fund internal improvements.

Meanwhile, the Federalist Party crumbled. As one supporter explained, the National Republicans in the eastern states had “destroyed the Federalist party by the adoption of its principles” while the favorable farm policies of Jeffersonians maintained the Republican Party’s dominance in the South and West. “No Federal character can run with success,” Gouverneur Morris of New York lamented, and the election of 1818 proved him right: Republicans outnumbered Federalists 37 to 7 in the Senate and 156 to 27 in the House. Westward expansion and the success of Jefferson’s Revolution of 1800 had shattered the First Party System.

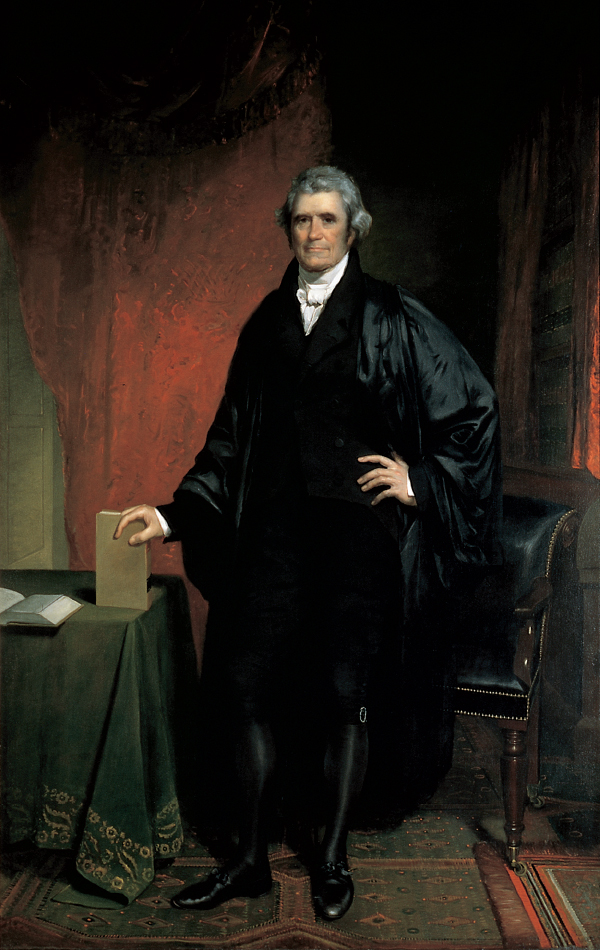

Marshall’s Federalist Law However, Federalist policies lived on thanks to John Marshall’s long tenure on the Supreme Court. Appointed chief justice by President John Adams in January 1801, Marshall had a personality and intellect that allowed him to dominate the Court until 1822 and strongly influence its decisions until his death in 1835.

Three principles informed Marshall’s jurisprudence: judicial authority, the supremacy of national laws, and traditional property rights (Table 7.1). Marshall claimed the right of judicial review for the Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madison (1803), and the Court frequently used that power to overturn state laws that, in its judgment, violated the Constitution.

| Major Decisions of the Marshall Court | |||

| Date | Case | Significance of Decision | |

| Judicial Authority | 1803 | Marbury v. Madison | Asserts principle of judicial review |

| Property Rights | 1810 | Fletcher v. Peck | Protects property rights through broad reading of Constitution’s contract clause |

| 1819 | Dartmouth College v. Woodward | Safeguards property rights, especially of chartered corporations | |

| Supremacy of National Law | 1819 | McCulloch v. Maryland | Interprets Constitution to give broad powers to national government |

| 1824 | Gibbons v. Ogden | Gives national government jurisdiction over interstate commerce | |

Asserting National Supremacy The important case of McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) involved one such law. When Congress created the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, it allowed the bank to set up state branches that competed with state-chartered banks. In response, the Maryland legislature imposed a tax on notes issued by the Baltimore branch of the Second Bank. The Second Bank refused to pay, claiming that the tax infringed on national powers and was therefore unconstitutional. The state’s lawyers then invoked Jefferson’s argument: that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to charter a national bank. Even if a national bank was legitimate, the lawyers argued, Maryland could tax its activities within the state.

Marshall and the nationalist-minded Republicans on the Court firmly rejected both arguments. The Second Bank was constitutional, said the chief justice, because it was “necessary and proper,” given the national government’s control over currency and credit, and Maryland did not have the power to tax it.

The Marshall Court again asserted the dominance of national over state statutes in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). The decision struck down a New York law granting a monopoly to Aaron Ogden for steamboat passenger service across the Hudson River to New Jersey. Asserting that the Constitution gave the federal government authority over interstate commerce, the chief justice sided with Thomas Gibbons, who held a federal license to run steamboats between the two states.

Upholding Vested Property Rights Finally, Marshall used the Constitution to uphold Federalist notions of property rights. During the 1790s, Jefferson Republicans had celebrated “the will of the people,” prompting Federalists to worry that popular sovereignty would result in a “tyranny of the majority.” If state legislatures enacted statutes infringing on the property rights of wealthy citizens, Federalist judges vowed to void them.

Marshall was no exception. Determined to protect individual property rights, he invoked the contract clause of the Constitution to do it. The contract clause (in Article I, Section 10) prohibits the states from passing any law “impairing the obligation of contracts.” Economic conservatives at the Philadelphia convention had inserted the clause to prevent “stay” laws, which kept creditors from seizing the lands and goods of delinquent debtors. In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), Marshall greatly expanded its scope. The Georgia legislature had granted a huge tract of land to the Yazoo Land Company. When a new legislature cancelled the grant, alleging fraud and bribery, speculators who had purchased Yazoo lands appealed to the Supreme Court to uphold their titles. Marshall did so by ruling that the legislative grant was a contract that could not be revoked. His decision was controversial and far-reaching. It limited state power; bolstered vested property rights; and, by protecting out-of-state investors, promoted the development of a national capitalist economy.

The Court extended its defense of vested property rights in Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819). Dartmouth College was a private institution created by a royal charter issued by King George III. In 1816, New Hampshire’s Republican legislature enacted a statute converting the school into a public university. The Dartmouth trustees opposed the legislation and hired Daniel Webster to plead their case. A renowned constitutional lawyer and a leading Federalist, Webster cited the Court’s decision in Fletcher v. Peck and argued that the royal charter was an unalterable contract. The Marshall Court agreed and upheld Dartmouth’s claims.

The Diplomacy of John Quincy Adams Even as John Marshall incorporated important Federalist principles into the American legal system, voting citizens and political leaders embraced the outlook of the Republican Party. The political career of John Quincy Adams was a case in point. Although he was the son of Federalist president John Adams, John Quincy Adams had joined the Republican Party before the War of 1812. He came to national attention for his role in negotiating the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war.

Adams then served brilliantly as secretary of state for two terms under James Monroe (1817–1825). Ignoring Republican antagonism toward Great Britain, in 1817 Adams negotiated the Rush-Bagot Treaty, which limited American and British naval forces on the Great Lakes. In 1818, he concluded another agreement with Britain setting the forty-ninth parallel as the border between Canada and the lands of the Louisiana Purchase. Then, in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, Adams persuaded Spain to cede the Florida territory to the United States (Map 7.6). In return, the American government accepted Spain’s claim to Texas and agreed to a compromise on the western boundary for the state of Louisiana, which had entered the Union in 1812.

Finally, Adams persuaded President Monroe to declare American national policy with respect to the Western Hemisphere. At Adams’s behest, Monroe warned Spain and other European powers to keep their hands off the newly independent republics in Latin America. The American continents were not “subject for further colonization,” the president declared in 1823 — a policy that thirty years later became known as the Monroe Doctrine. In return, Monroe pledged that the United States would not “interfere in the internal concerns” of European nations. Thanks to John Quincy Adams, the United States had successfully asserted its diplomatic leadership in the Western Hemisphere and won international acceptance of its northern and western boundaries.

The appearance of political consensus after two decades of bitter party conflict prompted observers to dub James Monroe’s presidency (1817–1825) the “Era of Good Feeling.” This harmony was real but transitory. The Republican Party was now split between the National faction, led by Clay and Adams, and the Jeffersonian faction, soon to be led by Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson. The two groups differed sharply over federal support for roads and canals and many other issues. As the aging Jefferson himself complained, “You see so many of these new [National] republicans maintaining in Congress the rankest doctrines of the old federalists.” This division in the Republican Party would soon produce the Second Party System, in which national-minded Whigs and state-focused Democrats would confront each other. By the early 1820s, one cycle of American politics and economic debate had ended, and another was about to begin.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW