The North and South Grow Apart

European visitors to the United States agreed that North and South had distinct characters. A British observer labeled New England the home to religious “fanaticism” but added that “the lower orders of citizens” there had “a better education, [and were] more intelligent” than those he met in the South. “The state of poverty in which a great number of white people live in Virginia” surprised the Marquis de Chastellux. Other visitors to the South likewise commented on the rude manners, heavy drinking, and weak work ethic of its residents. White tenants and smallholding farmers seemed only to have a “passion for gaming at the billiard table, a cock-fight or cards,” and rich planters squandered their wealth on extravagant lifestyles while their slaves endured bitter poverty.

Some southerners worried that human bondage had corrupted white society. “Where there are Negroes a White Man despises to work,” one South Carolina merchant commented. Moreover, well-to-do planters, able to hire tutors for their own children, did little to provide other whites with elementary schooling. In 1800, elected officials in Essex County, Virginia, spent about 25 cents per person for local government, including schools, while their counterparts in Acton, Massachusetts, allocated about $1 per person. This difference in support for education mattered: by the 1820s, nearly all native-born men and women in New England could read and write, while more than one-third of white southerners could not.

Slavery and National Politics As the northern states ended human bondage, the South’s commitment to slavery became a political issue. At the Philadelphia convention in 1787, northern delegates had reluctantly accepted clauses allowing slave imports for twenty years and guaranteeing the return of fugitive slaves. Seeking even more protection for their “peculiar institution,” southerners in the new national legislature won approval of James Madison’s resolution that “Congress have no authority to interfere in the emancipation of slaves, or in the treatment of them within any of the States.”

Nonetheless, slavery remained a contested issue. The black slave revolt in Haiti brought 6,000 white and mulatto planters and their slaves to the United States in 1793, and stories of Haitian atrocities frightened American slave owners. Meanwhile, northern politicians assailed the British impressment of American sailors as just “as oppressive and tyrannical as the slave trade” and demanded the end of both. When Congress outlawed the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, some northern representatives demanded an end to the trade in slaves between states. Southern leaders responded with a forceful defense of their labor system. “A large majority of people in the Southern states do not consider slavery as even an evil,” declared one congressman. The South’s political clout — its domination of the presidency and the Senate — ensured that the national government would protect slavery. American diplomats vigorously demanded compensation for slaves freed by British troops during the War of 1812, and Congress enacted legislation upholding slavery in the District of Columbia.

African Americans Speak Out Heartened by the end of the Atlantic slave trade, black abolitionists spoke out. In speeches and pamphlets, Henry Sipkins and Henry Johnson pointed out that slavery — “relentless tyranny,” they called it — was a central legacy of America’s colonial history. For inspiration, they looked to the Haitian Revolution; for collective support, they joined in secret societies, such as Prince Hall’s African Lodge of Freemasons in Boston. Initially, black (and white) antislavery advocates hoped that slavery would die out naturally as the tobacco economy declined. However, a boom in cotton planting dramatically increased the demand for slaves, and Louisiana (1812), Mississippi (1817), and Alabama (1819) joined the Union with state constitutions permitting slavery.

As some Americans redefined slavery as a problem rather than a centuries-old social condition, a group of prominent citizens founded the American Colonization Society in 1817. According to Henry Clay — a society member, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and a slave owner — racial bondage hindered economic progress. It had placed his state of Kentucky “in the rear of our neighbors … in the state of agriculture, the progress of manufactures, the advance of improvement, and the general prosperity of society.” Clay and other colonizationists argued that slaves had to be freed and then resettled, in Africa or elsewhere; emancipation without removal would lead to chaos — “a civil war that would end in the extermination or subjugation of the one race or the other.” Given the cotton boom, few planters responded to the society’s plea. It resettled only about 6,000 African Americans in Liberia, its colony on the west coast of Africa.

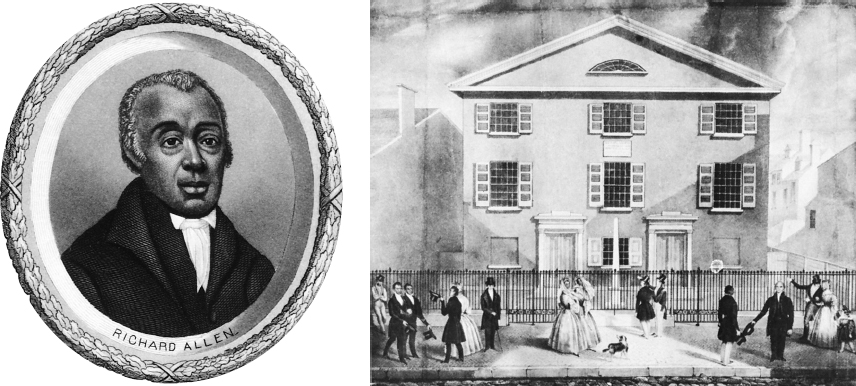

Most free blacks strongly opposed such colonization schemes because they saw themselves as Americans. As Bishop Richard Allen of the African Methodist Episcopal Church put it, “[T]his land which we have watered with our tears and our blood is now our mother country.” Allen spoke from experience. Born into slavery in Philadelphia in 1760 and sold to a farmer in Delaware, Allen grew up in bondage. In 1777, Freeborn Garretson, an itinerant preacher, converted Allen to Methodism and convinced Allen’s owner that on Judgment Day, slaveholders would be “weighted in the balance, and … found wanting.” Allowed to buy his freedom, Allen enlisted in the Methodist cause, becoming a “licensed exhorter” and then a regular minister in Philadelphia. In 1795, Allen formed a separate black congregation, the Bethel Church; in 1816, he became the first bishop of a new denomination: the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Two years later, 3,000 African Americans met in Allen’s church to condemn colonization and to claim American citizenship. Sounding the principles of democratic republicanism, they vowed to defy racial prejudice and advance in American society using “those opportunities … which the Constitution and the laws allow to all.”

EXPLAIN CONSEQUENCES