The Middle Class

Standing between wealthy owners and propertyless wage earners was a growing middle class — the social product of increased commerce. The “middling class,” a Boston printer explained, was made up of “the farmers, the mechanics, the manufacturers, the traders, who carry on professionally the ordinary operations of buying, selling, and exchanging merchandize.” Professionals with other skills — building contractors, lawyers, surveyors, and so on — were suddenly in great demand and well compensated, as were middling business owners and white-collar clerks. In the Northeast, men with these qualifications numbered about 30 percent of the population in the 1840s. But they also could be found in small towns of the agrarian Midwest and South. In 1854, the cotton boomtown of Oglethorpe, Georgia (population 2,500), boasted eighty “business houses” and eight hotels.

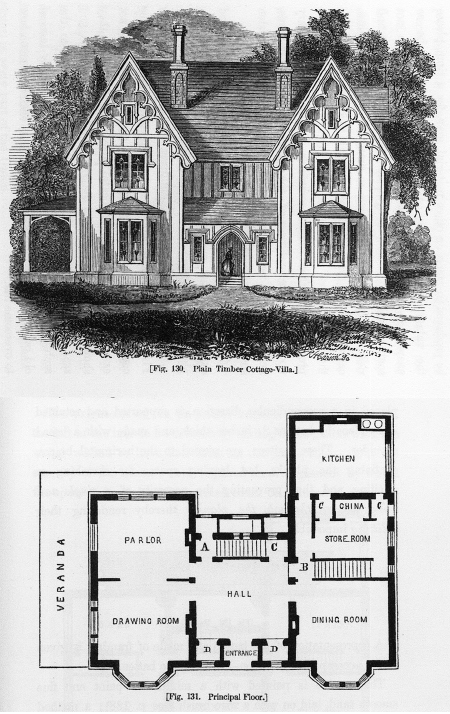

The emergence of the middle class reflected a dramatic rise in prosperity. Between 1830 and 1857, the per capita income of Americans increased by about 2.5 percent a year, a remarkable rate that has never since been matched. This surge in income, along with an abundance of inexpensive mass-produced goods, fostered a distinct middle-class urban culture. Middle-class husbands earned enough to save about 15 percent of their income, which they used to buy well-built houses in a “respectable part of town.” They purchased handsome clothes and drove to work and play in smart carriages. Middle-class wives became purveyors of genteel culture, buying books, pianos, lithographs, and comfortable furniture for their front parlors. Upper-middle-class families hired Irish or African American domestic servants, while less prosperous folk enjoyed the comforts provided by new industrial goods. The middle class outfitted their residences with furnaces (to warm the entire house and heat water for bathing), cooking stoves with ovens, and Singer’s treadle-operated sewing machines. Some urban families now kept their perishable food in iceboxes, which ice-company wagons periodically refilled, and bought many varieties of packaged goods. As early as 1825, the Underwood Company of Boston was marketing jars of well-preserved Atlantic salmon.

If material comfort was one distinguishing mark of the middle class, moral and mental discipline was another. Middle-class writers denounced raucous carnivals and festivals as a “chaos of sin and folly, of misery and fun” and, by the 1830s, had largely suppressed them. Ambitious parents were equally concerned with their children’s moral and intellectual development. To help their offspring succeed in life, middle-class parents often provided them with a high school education (in an era when most white children received only five years of schooling) and stressed the importance of discipline and hard work. American Protestants had long believed that diligent work in an earthly “calling” was a duty owed to God. Now the business elite and the middle class gave this idea a secular twist by celebrating work as the key to individual social mobility and national prosperity.

Benjamin Franklin gave the classic expression of this secular work ethic in his Autobiography, which was published in full in 1818 (thirty years after his death) and immediately found a huge audience. Heeding Franklin’s suggestion that an industrious man would become a rich one, tens of thousands of young American men saved their money, adopted temperate habits, and aimed to rise in the world. There was an “almost universal ambition to get forward,” observed Hezekiah Niles, editor of Niles’ Weekly Register. Warner Myers, a Philadelphia housepainter, rose from poverty by saving his wages, borrowing from his family and friends, and becoming a builder, eventually constructing and selling sixty houses. Countless children’s books, magazine stories, self-help manuals, and novels recounted the tales of similar individuals. The self-made man became a central theme of American popular culture and inspired many men (and a few women) to seek success. Just as the yeoman ethic had served as a unifying ideal in pre-1800 agrarian America, so the gospel of personal achievement linked the middle and business classes of the new industrializing society.

UNDERSTAND POINTS OF VIEW

Question

NZqujEsYJAtv85m21s/u1k75rYbsQ1Phx/VbLukz1wnqC1XH6C2uUFC1QsTr7mX4vbnKYyLSlhe5/3ly1/9hbRxbR6fd2CUcsrFl96uZ9TGZwbhCQGJGMNjApZ0=PLACE EVENTS IN CONTEXT