Slaves Fuel the Southern Economy

The labor of enslaved blacks drove the nation’s economy as well as the South’s. In 1820 the South produced some 500,000 bales of cotton, much of it exported to England. By 1850 the region produced nearly 3 million bales, feeding textile mills in New England and abroad. A decade later, cotton accounted for nearly two-thirds of the U.S. export trade and added nearly $200 million a year to the American economy.

Carpenters, blacksmiths, and other skilled slaves were sometimes hired out and allowed to keep a small amount of the money they earned. They traveled to nearby households, compared their circumstances to those on other plantations, and sometimes made contact with free blacks. Some skilled slaves also learned to read and write and had access to tools and knowledge denied to field hands. And they were less likely to be sold to slave traders. Still, they were constantly hounded by whites who demanded travel passes and deference, were more acutely aware of alternatives to slavery, and were often suspected of involvement in rebellions.

Household slaves sometimes received old clothes and bedding or leftover food from their owners. Yet they were under the constant surveillance of whites, and women especially were vulnerable to sexual abuse. Moreover, the work they performed was physically demanding. Enslaved women chopped wood, hauled water, baked food, and washed clothes. Fugitive slave James Curry recalled that his mother, a cook in North Carolina, rose early each morning to milk fourteen cows, bake bread, and churn butter. She was responsible for meals for her owners and the slaves. In summer, she cooked her last meal around eight o’clock, after which she milked the cows again. Then she returned to her quarters, put her children to bed, and often fell asleep while mending clothes. See e-Document Project 10: Life in Slavery.

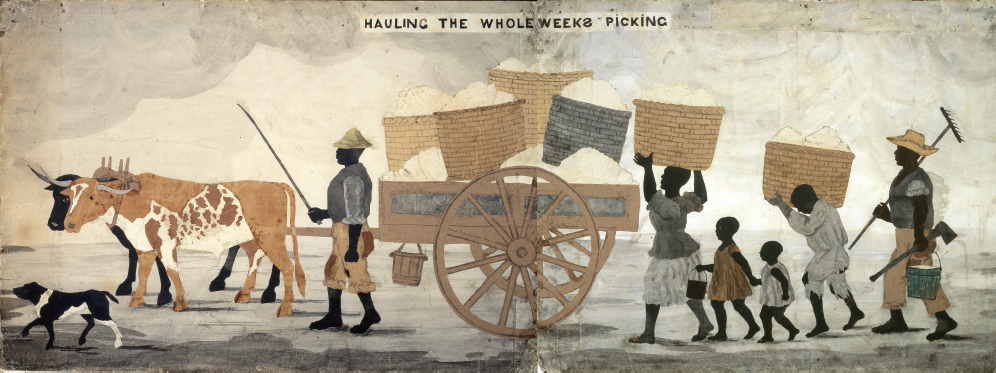

Field hands often left their youngest children in the care of cooks and washerwomen. But once slaves reached the age of eleven or twelve, they were put to work full-time. Although field labor was defined by its relentless pace and drudgery, it also brought together large numbers of slaves for the entire day and thus helped forge bonds among laborers on the same plantation. Songs provided a rhythm for their work and offered slaves the chance to communicate their frustrations or their hopes.

Field labor was generally organized by task or by gang. Under the task system, typical on rice plantations, a slave could return to his or her quarters once the day’s task was completed. This left time for some slaves to cultivate gardens, fish for supper, make quilts, or repair furniture. In the gang system, widely used on cotton plantations, men and women worked in groups under the supervision of a driver and swept across fields hoeing, planting, or picking.