The Second Great Awakening

Although diverse religious traditions flourished in the United States, evangelical Protestantism proved the most powerful in the 1820s and 1830s. Evangelical churches hosted revivals, encouraged conversions, and organized prayer and missionary societies. This second wave of religious revivals began in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801, took root across the South, and then spread northward. Although revivals had diminished by the late 1830s, they erupted periodically through the 1850s and again during the Civil War. But it was the revivals of the 1830s that transformed Protestant churches and the social fabric of northern life.

Northern ministers like Charles Grandison Finney adopted techniques first wielded by southern Methodists and Baptists: plain speaking, powerful images, and mass meetings. But Finney molded these techniques for a more affluent audience and held his “camp meetings” in established churches. Northern evangelicals also insisted that religious fervor demanded social responsibility and that good works were a sign of salvation.

In the late 1820s, boomtown growth along the Erie Canal aroused deep concerns about the rising tide of sin. In September 1830, the Reverend Finney arrived in Rochester and began preaching in the city’s Presbyterian churches. Arguing that “nothing is more calculated to beget a spirit of prayer, than to unite in social prayer with one who has the spirit himself,” Finney led prayer meetings that lasted late into the night. Individual supplicants walked to special benches designated for anxious sinners, who were prayed over in public. Female parishioners played crucial roles, encouraging their husbands, sons, friends, and neighbors to submit to God.

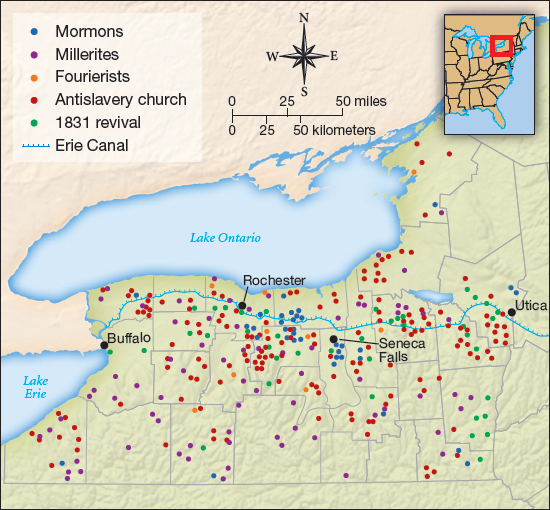

Thousands of Rochester residents joined in the evangelical experience as Finney’s powerful message spilled over into other denominations (Map 11.1). But the significance of the Rochester revivals went far beyond a mere increase in church membership. Finney had converted “the great mass of the most influential people” in the city: merchants, lawyers, doctors, master craftsmen, and shopkeepers. Equally important, he proclaimed that if Christians were “united all over the world the Millennium [Christ’s Second Coming] might be brought about in three months.” Local preachers in Rochester and the surrounding towns took up his call, and converts committed themselves to preparing the world for Christ’s arrival.

Lyman Beecher, a powerful Presbyterian minister in Boston, declared that the spiritual renewal of the early 1830s was the greatest revival of religion the world had ever seen. Middle-class and wealthy Americans were swept into Presbyterian, Congregational, and Episcopalian churches, while Baptists and Methodists ministered mainly to laboring women and men. Black Baptists and Methodists evangelized in their own communities, where independent black churches combined powerful preaching with haunting spirituals. In Philadelphia, African Americans built fifteen churches between 1799 and 1830. Over the next two decades, a few black women, such as Jarena Lee, joined men in evangelizing among African American Methodists and Baptists.

Tens of thousands of Christian converts both black and white embraced evangelicals’ message of moral outreach. They formed Bible, missionary, and charitable societies; Sunday schools; and reform organizations. No movement gained greater impetus from the revivals than did temperance, which sought to moderate and then ban the sale and consumption of alcohol. In the 1820s, Americans fifteen years and older consumed six to seven gallons of distilled alcohol per person per year (about double the amount consumed today). Middle-class evangelicals, who once accepted moderate drinking as healthful and proper, now insisted on eliminating alcohol consumption in the United States.