The Lure of Urban Life

Across the North, urban populations boomed. As centers of national and international commerce, seaports like New York and Philadelphia gained the greatest population in the early to mid-nineteenth century. But boomtowns also emerged along inland waterways. Rochester, New York, first settled in 1812, was flooded by goods and people once the Erie Canal was completed in 1825. Between 1820 and 1850, the number of cities with 100,000 inhabitants grew from two to six. In the Northeast, some farm communities doubled or tripled in size and were incorporated into neighboring cities such as Philadelphia. By 1850, among the nation’s ten most populous urban centers, only two—Baltimore and New Orleans—were located in the South.

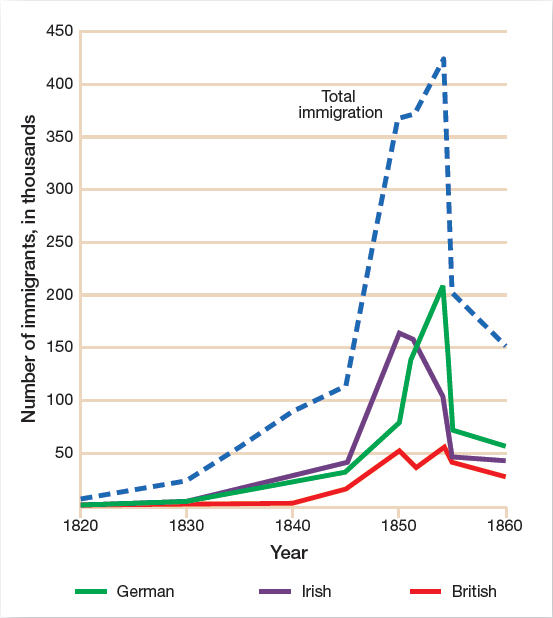

Cities increased not only in size but also in the diversity of their residents. During the 1820s, some 150,000 European immigrants entered the United States; during the 1830s, nearly 600,000; and during the 1840s, more than 1,700,000. This surge of immigrants included more Irish and German settlers than ever before as well as large numbers of Scandinavians. Many settled along the eastern seaboard, but others added to the growth of frontier cities such as Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Chicago.

Irish families had settled in North America early on, most of them Scots-Irish Presbyterians. Then in the 1830s and 1840s, the Irish countryside was plagued by bad weather, a potato blight, and harsh economic policies imposed by the English government. In 1845–1846 a full-blown famine forced thousands of Irish farm families—most of them Catholic—to emigrate. Young Irish women emigrated in especially large numbers, working as seamstresses and domestics to help fund passage to the United States for other family members. Poor harvests, droughts, failed revolutions, and repressive landlords convinced large numbers of Germans and Scandinavians to flee their homelands as well. By 1850 the Irish made up about 40 percent of immigrants to the United States, and Germans nearly a quarter (Figure 11.1).

Commerce and industry attracted immigrants to northern cities. These newcomers provided an expanding pool of cheap labor that further fueled economic growth. Banks, mercantile houses, and dry goods stores multiplied. Industrial enterprises in cities such as New York and Philadelphia included mechanized factories as well as traditional workshops in which master craftsmen oversaw the labor of apprentices. Credit and insurance agencies were created to aid entrepreneurs in their ventures. The increase in business also drove the demand for ships, newspapers catering to merchants and businessmen, warehouses, and other trade necessities, which created a surge in jobs and attracted even more people.

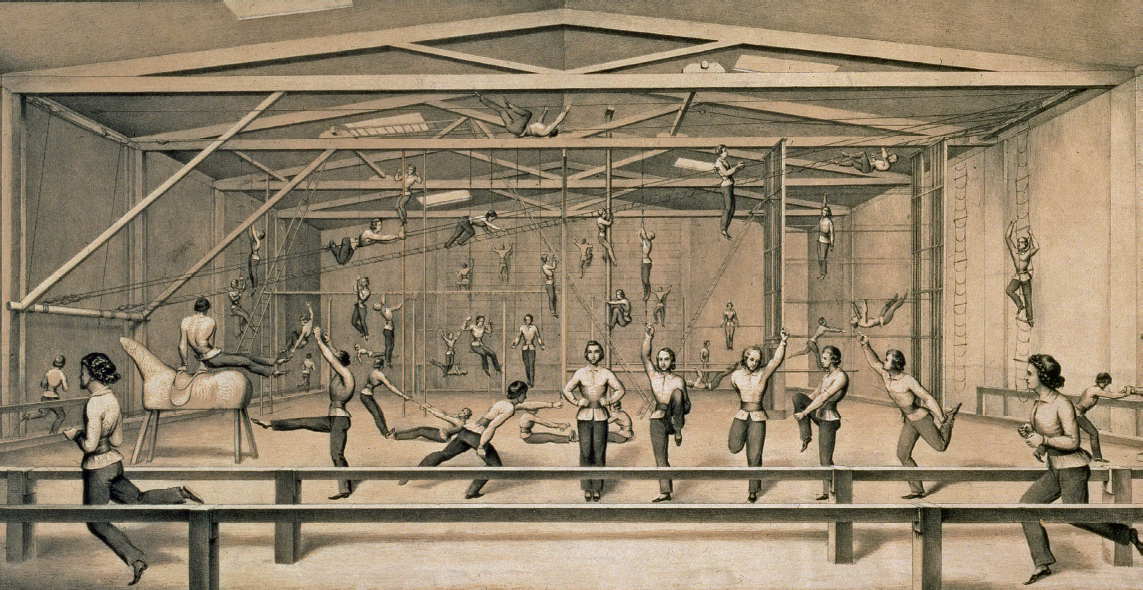

Businesses that focused on leisure also flourished. In the 1830s, theater became affordable to working-class families, who attended comedies, musical revues, and morality plays. They also joined middle- and upper-class audiences at productions of Shakespeare and nationalistic dramas in which strong and clever Americans triumphed over English aristocrats. Minstrel shows mocked self-important capitalists but also portrayed African Americans in crude caricatures. One of the most popular characters was Jim Crow, who appeared originally in an African American song. In the 1820s, he was incorporated into a song-and-dance routine by Thomas Rice, a white performer who blacked his face with burnt cork.

Museums, too, became a favorite destination for city dwellers. Many were modeled on P. T. Barnum’s American Museum on lower Broadway in New York City. These museums were not staid venues for observing the fine arts or historical artifacts. Instead, they offered an abundance of exhibits and entertainment, including wax figures, archaeological antiquities, medical instruments, and insect collections, as well as fortune-tellers, bearded ladies, and snake charmers.

The lures of urban life were especially attractive to the young. Single men and women and newly married couples flocked to cities. By 1850 half the residents of New York City, Philadelphia, and other seaport cities were under sixteen years old. Young men sought work in construction, in the maritime trades, or in banks and commercial houses, while young women competed for jobs as seamstresses and domestic servants.