The Gold Rush

Despite the hazards, more and more Americans traveled the Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, and other paths to the Pacific coast. Initially only a few thousand Americans settled in California. Some were agents sent by New England merchants to purchase fine leather made from the hides of Spanish cattle raised in the area. Several of these agents married into families of elite Mexican ranchers, known as Californios, and adopted their culture, even converting to Catholicism.

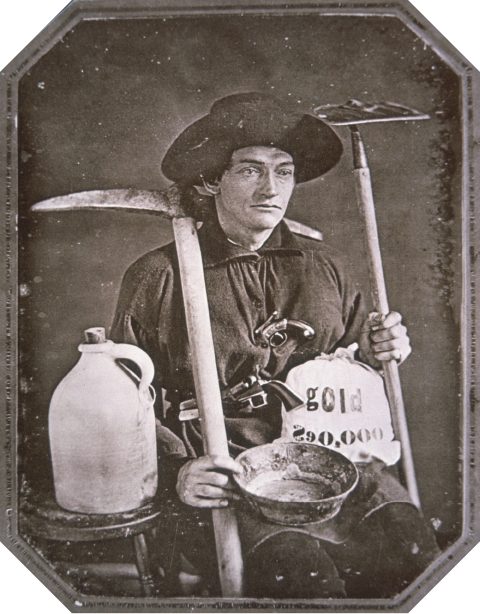

However, the Anglo-American presence in California changed dramatically after 1848 when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in northeastern California. News of the discovery brought tens of thousands of new settlers from the eastern United States, South America, Europe, and Asia. In the gold rush, “forty-niners” raced to claim riches in the California mountains, and men vastly outnumbered women. Single men came with brothers, neighbors, or friends. Married men left wives and children behind, promising to send for them once they struck gold. Some 80,000 arrived in 1849 alone.

The rapid influx of gold seekers heightened tensions between newly arrived whites, local Indians, and Californios. Forty-niners confiscated land owned by Californios, shattered the fragile ecosystem in the California mountains, and forced Mexican and Indian men to labor for low wages or a promised share in uncertain profits. New conflicts erupted when foreign-born migrants joined the search for wealth. Forty-niners from the United States regularly stole from and assaulted foreign-born competitors—whether Asian, European, or South American. With the limited number of sheriffs and judges in the region, most criminals knew they were unlikely to be arrested, much less tried and convicted.

The gold rush also led to conflicts over gender roles as thousands of male migrants demanded food, shelter, laundry, and medical care. Some women in the region earned a good living by renting rooms, cooking meals, washing clothes, or working as prostitutes. But many faced heightened forms of exploitation. Indian and Mexican women were especially vulnerable to sexual harassment and rape, while Chinese women were imported specifically to provide sexual services for male miners.

Chinese men were also victims of abuse by whites, as evidenced by Chinese workers who were hired by a British mining company and then run off their claim by Anglo-American gold seekers. Yet some Chinese men used the skills traditionally assigned them in their homeland—cooking and washing clothes—to earn a far steadier income than prospecting for gold could provide. Other men also took advantage of the demand for goods and services. Levi Strauss, a twenty-four-year-old German Jewish immigrant, moved from New York to San Francisco to open a dry goods store in 1853. He was soon producing canvas and then denim pants that could withstand harsh weather and long wear. These blue jeans made Strauss far richer than any forty-niner seeking gold.