Dissent and Protest in the Midst of War

While the Women’s National Loyal League lobbied Congress for universal emancipation, other Northerners wondered whether defeating the Confederacy was worth the cost. Families were hard hit as wages fell and prices rose, and many Northerners cared more about the safe return of their husbands and sons than the fate of slavery. As the war dragged on, these concerns led to a rising tide of dissent and protest. See e-Document Project 13: Home Front Protest during the Civil War.

Despite the expanding economy, northern farmers and workers suffered tremendously during the war. Women, children, and old men took over much of the field labor in the Midwest, trying to feed their families and produce sufficient surplus to supply the army and pay their mortgages and other expenses. In the East, too, inflation eroded the earnings of factory workers, servants, and day laborers. As federal greenbacks flooded the market and military production took priority over consumer goods, prices climbed about 20 percent faster than wages. While industrialists garnered huge profits, railroad stocks leaped to unheard-of prices, and government contractors made huge gains, ordinary workers suffered. A group of Cincinnati seamstresses complained to President Lincoln in 1864 about employers “who fatten on their contracts by grinding immense profits out of the labor of their operatives.” Although Republicans pledged to protect the rights of workers, employers successfully lobbied a number of state legislatures to pass laws prohibiting strikes. The federal government, too, proved a better friend to business than to labor. When workers at the Parrott arms factory in Cold Spring, New York, struck for higher wages in 1864, the government sent in troops, declared martial law, and arrested the strike leaders.

Discontent intensified when the Republican Congress passed a draft law in March 1863. The Enrollment Act provided for draftees to be selected by an impartial lottery, but a loophole allowed a person with $300 to pay the government in place of serving or to hire another man as a substitute. Many workers deeply resented the draft law’s profound inequality. Some also opposed the emancipation of slaves who, they assumed, would compete for scarce jobs once the war ended.

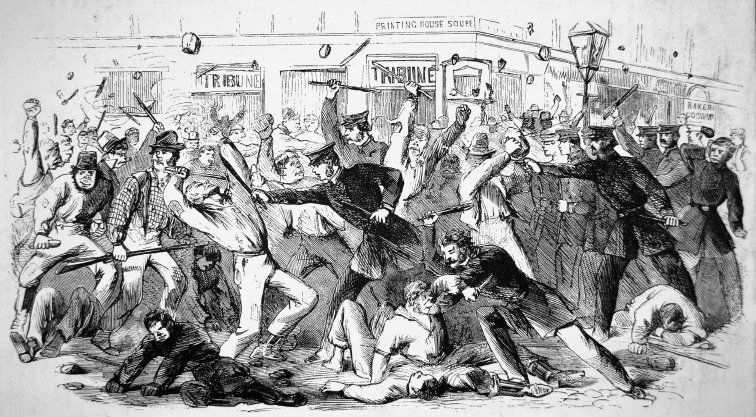

Dissent turned to violence in July 1863 when the new draft law went into effect. Riots broke out in cities across the North. In New York City, where inflation caused tremendous suffering and a large immigrant population solidly supported the Democratic machine, implementation of the draft triggered four days of the worst rioting Americans had ever seen. Women and men—many of them Irish and German immigrants—attacked Protestant missionaries, Republican draft officials, and wealthy businessmen. Homes in wealthy neighborhoods were looted, but the free black community became the rioters’ main target. Rioters lynched at least a dozen African Americans and looted and burned the city’s Colored Orphan Asylum. The violence ended only when Union troops put down the riot by force. By then, more than one hundred New Yorkers lay dead.

A more prolonged battle raged in Missouri, where Confederate sympathizers never reconciled themselves to living in a Union state. From the beginning of this “inner civil war,” prosouthern residents formed militias and staged guerrilla attacks on Union supporters. The militias, with the tacit support of Confederate officials, claimed thousands of lives and forced the Union army to station troops in the area. The militia members hoped that Midwesterners, weary of the conflicts, would elect peace Democrats and end the war.

Northern Democrats saw the widening unrest as a political opportunity. Although some Democratic leaders supported the war effort, many others—whom opponents called Copperheads, after the poisonous snake—rallied behind Ohio politician Clement L. Vallandigham in opposing the war. Presenting themselves as the “peace party,” these Democrats enjoyed considerable success in eastern cities where inflation was rampant and immigrant workers were caught between low wages and military service. The party was also strong in parts of the Midwest where sympathy for the southern cause and antipathy to African Americans ran deep.

In the South, too, some whites expressed growing dissatisfaction with the war. In April 1862, Jefferson Davis had signed the first conscription act in U.S. history, inciting widespread opposition. The concept of a national draft undermined the southern tradition of states’ rights. As in the North, men could hire a substitute if they had enough money, and an October 1862 law exempted men owning twenty or more slaves from military service. Although the exemption was supposedly a response to growing unruliness among slaves in the absence of masters, in practice it meant that large planters, many of whom served in the Confederate legislature, had exempted themselves from fighting. As one Alabama farmer fumed, “All they want is to get you pumpt up and go to fight for their infernal negroes, and after you do their fighting you may kiss their hine parts for all they care.”

Small farmers were also hard hit by policies that allowed the Confederate army to take whatever supplies it needed. The army’s forced acquisition of farm produce intensified food shortages that had been building since early in the war. The southern economy was rooted in cash crops rather than foodstuffs. Quantities of grain and livestock were produced in South Carolina, central Virginia, and central Tennessee, but by 1863 the latter two areas had fallen under Union control. The Union blockade of port cities and the lack of an extensive railroad or canal system in the South limited the distribution of what food was available. Hungry residents of the Shenandoah Valley discovered that despite military victories there, food shortages worsened as Confederate troops ravaged the countryside.

Food shortages drove up prices on basic items like bread and corn, while the Union blockade and the focus on military needs dramatically increased the price of other consumer goods. As the Confederate government issued more and more treasury notes to finance the war, inflation soared 2,600 percent in less than three years. Food riots, often led by women, broke out in cities across the South, including the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Conscription, food shortages, and inflation took their toll on support for the Confederacy. The devastation of the war itself added to these grievances. Most battles were fought in the Upper South or along the Confederacy’s western frontier, where small farmers saw their crops, animals, and fields destroyed. A phrase that had seemed cynical in 1862—“A rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight”—became the rallying cry of the southern peace movement in 1864. The Washington Constitutional Union, a secret peace society with a large following among farmers, elected several members to the Confederate Congress. Another secret organization centered in North Carolina took more drastic measures, providing Union forces with information on southern troop movements and encouraging desertion by Confederates. In mountainous regions of the South, draft evaders and deserters formed guerrilla groups that attacked draft officials and actively impeded the war effort. In western North Carolina, some women hid deserters, raided grain depots, and burned the property of Confederate officials.

When slaveholders led the South out of the Union in 1861, they had assumed the loyalty of yeomen farmers, the deference of southern ladies, and the privileges of the southern way of life. Far from preserving social harmony and social order, however, the war undermined ties between elite and poor Southerners, between planters and small farmers, and between women and men. Although most white Southerners still supported the Confederacy in 1864 and internal dissent alone did not lead to defeat, it did weaken the ties that bound soldiers to their posts in the final two years of the war.

Review & Relate

|

What were the short- and long-term economic effects of the war on the North? |

How did the war change the southern economy? What social tensions did the war create in the South? |