Key Victories for the Union

In mid-1863, Confederate commanders believed the tide was turning in their favor. Following victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, General Lee launched an invasion of northern territory. While the Union army maneuvered to protect Washington, D.C., from Lee’s advance, General Joseph Hooker resigned as head of the Union army. When Lincoln appointed George A. Meade as the new Union commander, the general immediately faced a major engagement at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. If Confederates won a victory there, European countries might finally recognize the southern nation and force the North to accept peace.

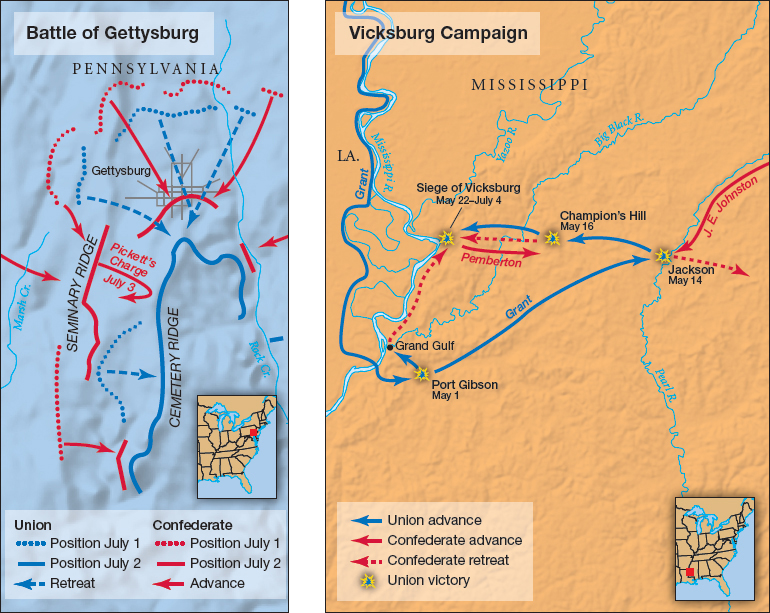

Neither Lee nor Meade set out to launch a battle in this small Pennsylvania town. But Lee was afraid of outrunning his supply lines, and Meade wanted to keep Confederates from gaining control of the roads that crossed at Gettysburg. So on July 1, fighting commenced, with Lee pushing Union forces to the south of town. The Union vanguard managed to hold the ground along Cemetery Ridge until more troops arrived the following day. Although Confederate troops suffered heavy losses on July 2, Lee believed that Union forces were spread thin and ordered General George Pickett to launch a frontal assault on July 3 (Map 13.2). But Pickett’s men were mowed down as they crossed an open field. The battle was a disaster for the South: More than 4,700 Confederates were killed, including a large number of officers; another 18,000 were wounded, captured, or missing. Although the Union suffered similar casualties, it had more men to lose, and it could claim victory.

As a grieving Lee retreated to Virginia, the South suffered another devastating defeat. Troops under General Ulysses S. Grant had been pounding Vicksburg, Mississippi, for months. In May 1863, Grant sent his men in a wide arc around the city and attacked from the east, setting the stage for a six-week siege. Although civilians refused to leave and even hid out in caves to outlast the Union barrage, Confederate troops were forced to surrender the city on July 4. This victory was even more important strategically than Gettysburg (Map 13.2). Combined with a victory five days later at Port Hudson, Louisiana, the Union army now controlled the entire Mississippi valley, the richest plantation region in the South. This series of victories also effectively cut off the Confederacy from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, ensuring Union control of the West. In November 1863, Grant’s troops achieved a major victory at Chattanooga, opening up much of the South’s remaining territory to invasion. Thousands of slaves deserted their plantations, and many joined the Union war effort.

As 1864 dawned, the Union had twice as many forces in the field as the Confederacy, whose soldiers were suffering from low morale, high mortality, and dwindling supplies. Although some difficult battles still lay ahead, the war of attrition (in which the larger, better-supplied Union forces slowly wore down their Confederate opponents) had begun to pay dividends.

The changing Union fortunes increased support for Lincoln and his congressional allies. Union victories and the Emancipation Proclamation also convinced Great Britain not to recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation. And the heroics of African American soldiers, who in 1863 engaged in direct and often brutal combat against southern troops, encouraged wider support for emancipation. Republicans, who now fully embraced abolition as a war aim, were nearly assured the presidency and a congressional majority in the 1864 elections.

Northern Democrats still campaigned for peace and the readmission of Confederate states with slavery intact. They nominated George B. McClellan, the onetime Union commander, as their candidate for president. McClellan attracted working-class and immigrant voters who traditionally supported the Democrats and who bore the heaviest burdens of the war. But Democratic hopes for victory in November were crushed when Union general William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia, just two months before the election. Lincoln and the Republicans won easily, giving the party a clear mandate to continue the war to its conclusion.