African Americans Contribute to Victory

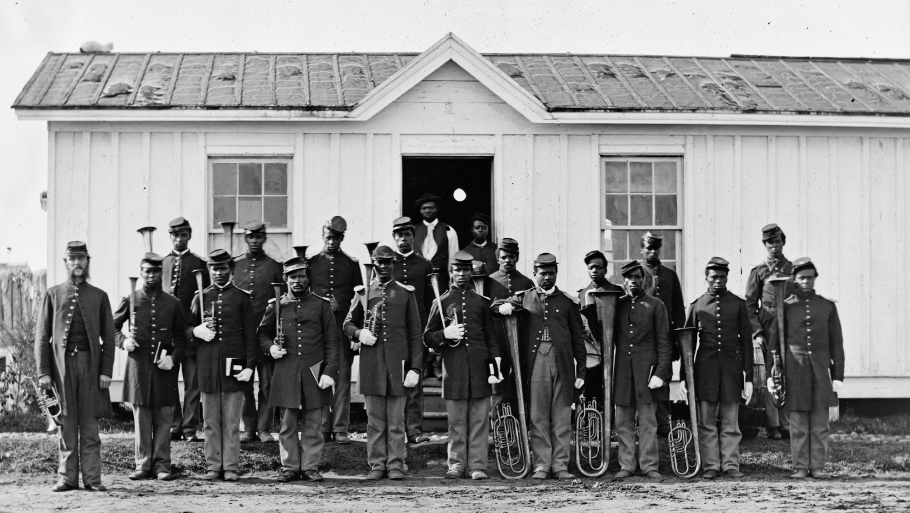

Lincoln’s election secured the eventual downfall of slavery. Yet neither the president nor Congress eradicated human bondage on their own. From the fall of 1862 on, African Americans enlisted in the Union army and helped ensure that nothing short of universal emancipation would be the outcome of the war. By the spring of 1865, nearly 200,000 African Americans were serving in the Union army and navy. Private Thomas Long, a former slave serving with the First South Carolina Volunteers, explained the connection between African American enlistment and emancipation: “If we hadn’t become sojers, all might have gone back as it was before; our freedom might have slipped through de two houses of Congress and President Linkum’s four years might have passed by and notin’ been done for us. But now tings can neber go back, because we have showed our energy and our courage and our naturally manhood.”

In the border states, which were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, enslaved men were adamant about enlisting since those who served in the Union army were granted their freedom. Because of this provision, slaveholders in the border states did everything in their power to prevent their slaves from joining the army, including assault and even murder. Despite these efforts, between 25 and 60 percent of military-age enslaved men in the four border states joined the Union army and quickly distinguished themselves in battle. By the end of the war, approximately 37,000 black soldiers had given their lives for freedom and the Union.

Yet despite their courage and commitment, black soldiers felt the sting of racism. They were segregated in camps, given the most menial jobs, and often treated as inferiors by white recruits and officers. Many blacks, for instance, were assigned the gruesome and exhausting task of burying the dead after grueling battles in which they had fought alongside whites. Particularly galling was the Union policy of paying black soldiers less than whites were paid. African American soldiers openly protested this discrimination even after a black sergeant who voiced his views was charged with mutiny and executed by firing squad in February 1864. An African American corporal wrote to Lincoln, describing the blood black troops had shed for the Union and asking, “We have done a Soldier’s Duty. Why can’t we have a Soldier’s pay?” The War Department finally equalized wages in June 1864.

One of African American soldiers’ primary concerns was to liberate slaves as Union armies moved deeper into the South. During 1863 and 1864, thousands more slaves headed for Union lines, joining the “contraband” who had escaped earlier in the war. Even those forced to remain on plantations realized that Union troops and freedom were headed their way. In areas close to Union lines, they talked openly of the advancing army. “Now they gradually threw off the mask,” a slave remembered of this moment, “and were not afraid to let it be known that the ‘freedom’ in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world.”