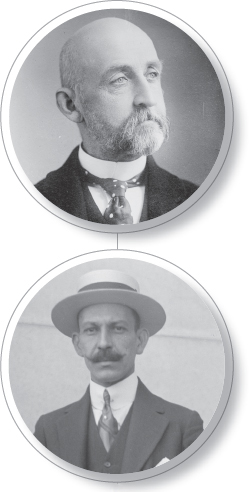

American Histories: Alfred Thayer Mahan and JJosé Martí

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Alfred Thayer Mahan came from a military family. Born in 1840, he grew up in West Point, New York, where his father served as dean of the faculty at the U.S. Military Academy. Seeking to emerge from his father’s shadow, Alfred attended the U.S. Naval Academy, from which he graduated and received his commission in 1861, just as the Civil War was getting under way. His wartime experience convinced him that the navy, with its plodding, antiquated wooden vessels, needed a dramatic overhaul.

After the war, Mahan continued his naval career. Rather than making his mark on the high seas, Captain Mahan built his reputation as a military historian and strategist at the U.S. Naval War College. In 1890 he published The Influence of Sea Power upon History, in which he argued that the great imperial powers in modern history—Spain, the Netherlands, Great Britain, and France—had succeeded because they possessed strong navies and merchant marines. In his view, sea power had allowed these nations to defeat their enemies, conquer territories, and establish colonies from which they extracted raw materials and opened markets for finished goods. Appearing at a time when European nations were embarking on a new round of empire building, this book and subsequent writings had an enormous influence on American imperialists, including Theodore Roosevelt. Mahan’s work reinforced the belief of men like Roosevelt that the long-term prospects of the United States depended on the acquisition of strategic outposts in Asia and the Caribbean that could guarantee American access to overseas markets.

As the economic and strategic importance of the Caribbean grew in the minds of imperial strategists such as Mahan and Roosevelt, the Cuban freedom fighter José Martí developed a very different vision of the region’s future. Born in 1853 to Spanish immigrants who had migrated to Cuba for economic reasons, Martí got involved in the fight for Cuban independence from Spain as a teenager. In 1869, at age seventeen, he was arrested for protest activities during a revolutionary uprising against Spain. Sentenced to six years of hard labor, Martí was released after six months and was forced into exile. He returned to Cuba in 1878, only to be arrested and deported again the following year.

Martí settled in the United States, where, along with other Cuban exiles, he continued to promote Cuban independence and the establishment of a democratic republic. He conceived of the idea of Cuba Libre (Free Cuba) not just as a struggle for political independence but also as a social revolution that would erase unfair distinctions based on race and class. “Our goal,” Martí declared in 1892, “is not so much a mere political change as a good, sound, and just and equitable system.” Martí united disparate elements in expatriate communities in the United States and the Caribbean under the banner of a single Cuban Revolutionary Party.

When Cubans once again rebelled against Spain in 1895, Martí returned to Cuba to fight alongside his comrades. On May 19, 1895, only three months after he had returned to Cuba, Martí died in battle. Cuba ultimately won its independence from Spain, but Martí’s vision of Cuba Libre was only partially realized. In 1898 the United States intervened on the side of the Cuban rebels, guaranteeing their victory, but not their freedom. America entered the war to gain control over Cuba, not to help Cubans take control of their own country. •

THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Alfred Thayer Mahan and José Martí embodied disparate understandings of America’s relationship with the rest of the world. Up until the late nineteenth century, most Americans associated colonialism with the European powers and saw overseas expansion as incompatible with American values of independence and self-determination. In this context, they shared Martí’s point of view. The American imperialism espoused by Mahan and others, therefore, represented a reversal of traditional American attitudes. Supporters of American imperialism saw the acquisition and control of overseas territories, by force if necessary, as essential to the protection of American interests. This perspective would come to dominate American foreign policy in the early twentieth century. Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, progressive presidents who sanctioned increased federal regulation of economic and moral matters within the United States, also supported vigorous intervention in world affairs. Although Roosevelt and Wilson differed in style and approach, in foreign affairs they asserted America’s right to use its power to secure order and thwart revolution wherever American interests were seen to be threatened. Having become a major power on the world stage in the early twentieth century, the United States chose to enter World War I, in which rival European alliances battled for imperial domination. The end of the war heightened America’s critical role in world affairs but brought neither lasting peace nor the dissolution of empire.