The Battle for the Soul of the Democratic Party

The 1924 presidential election exposed the social and cultural fault lines within the Democratic Party. Since the end of Reconstruction and the “redemption” of the South by southern Democrats, the Republican Party had ceased to compete for office in the region. Southern Democrats, along with party supporters from the rural Midwest, shared strong fundamentalist religious beliefs and an enthusiasm for prohibition that usually placed them at odds with big-city northern Democrats. The urban wing of the party increasingly represented immigrant populations that rejected prohibition as contrary to their social practices and supported political machines, which many rural Democrats found odious and an indicator of cultural degradation. These distinctions, however, were not absolute—some rural dwellers opposed prohibition, and some urbanites supported temperance.

Delegates to the 1924 Democratic convention in New York City had trouble deciding on a party platform and a presidential candidate. When urban delegates from the Northeast attempted to insert a plank condemning D. C. Stephenson’s Ku Klux Klan for its intolerance, they lost by a thin margin. Proponents of this measure owed their defeat to the sizable number of convention delegates who either belonged to the Klan or had been backed by it.

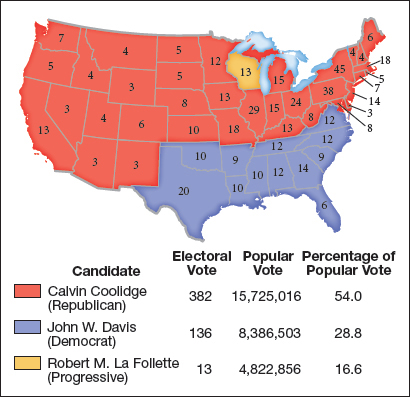

The selection of the presidential ticket proved even more divisive. Urban Democrats favored the nomination of New York governor Alfred E. Smith. Smith came from an Irish Catholic immigrant family, had grown up on New York City’s Lower East Side, and was sponsored by the Tammany Hall machine. The epitome of everything that rural Democrats despised, Smith further angered opponents with his outspoken denunciation of prohibition. Prohibitionists fiercely opposed Smith, and he lost the nomination to John W. Davis, a West Virginia Protestant and a supporter of prohibition. The intense intraparty fighting left the Democrats deeply divided going into the general election. To no one’s surprise, Davis lost to Calvin Coolidge in a landslide (Map 21.1).

In 1928, however, when the Democrats met in Houston, Texas, the delicate cultural equilibrium within the Democratic Party had shifted in favor of the urban forces. With Stephenson and the Klan discredited and no longer a force in Democratic politics, the delegates nominated Al Smith as their presidential candidate. To balance the ticket, they tapped for vice president Joseph G. Robinson, a senator from Arkansas, a Protestant, and a supporter of prohibition.

The Republicans selected Herbert Hoover, one of the most popular men in the United States. His biography read like a script of the American dream. Born in Iowa to a Quaker family, he became an orphan at the age of nine and moved to Oregon to live with relatives. After graduating from Stanford University in 1895, he began a career as a prosperous mining engineer and a successful businessman. Affectionately called “the Great Humanitarian” for his European relief efforts after World War I, Hoover served as secretary of commerce during the Harding and Coolidge administrations. His name became synonymous with the Republican prosperity of the 1920s. In accepting his party’s nomination for president in 1928, Hoover optimistically declared: “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of the land.” A Protestant supporter of prohibition from a small town, Hoover was everything Smith was not.

The outcome of the election proved predictable. Running on prosperity and pledging a “chicken in every pot and two cars in every garage,” Hoover trounced Smith with 58 percent of the popular vote and more than 80 percent of the electoral vote. Despite the weakening economy, Smith lost usually reliable Democratic votes to religious and ethnic prejudices. The New Yorker prevailed only in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and six southern states but failed to win his home state. A closer look at the election returns showed a significant party realignment under way. Smith succeeded in identifying the Democratic Party with urban, ethnic-minority voters and attracting them to the polls. Despite the landslide loss, he captured the twelve largest cities in the nation, all of which had gone Republican four years earlier. In another fifteen big cities, Smith did better than the Democrat ticket had done in the 1924 election, thereby encouraging the country’s ethnic minorities to support the party of Thomas Jefferson and Woodrow Wilson. To break the Republicans’ national dominance, the Democrats would need a candidate who appealed to both traditional and modern Americans. Smith’s defeat, however, laid the foundation for future Democratic political success.