Government Promotion of the Economy

The general prosperity of the 1920s owed a great deal to backing by the federal government. Republicans controlled the presidency and Congress, and though they claimed to stand for principles of laissez-faire and opposed various economic and social reforms, they were willing to use governmental power to support large corporations and the wealthy.

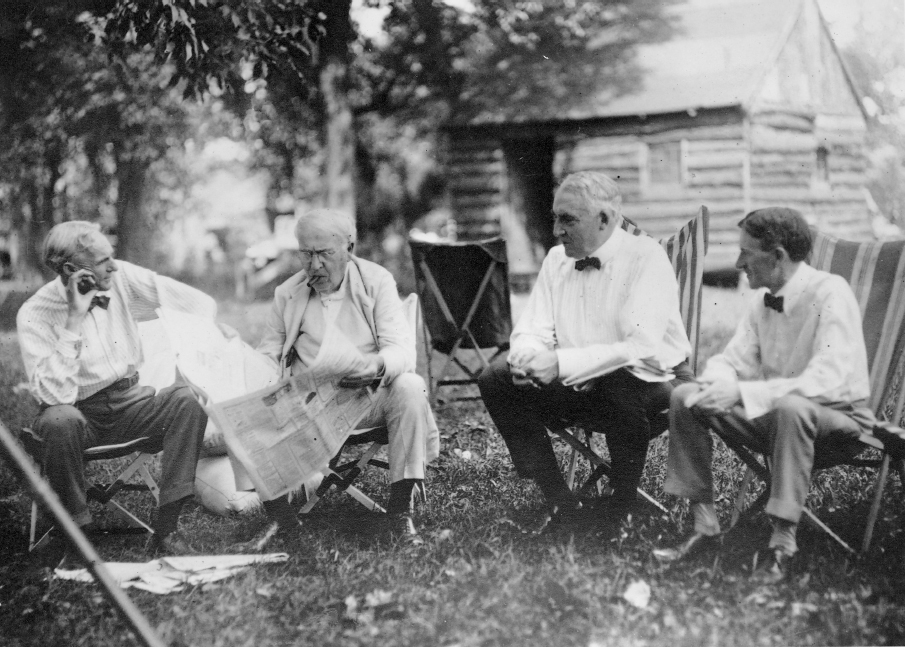

Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, who was elected president in 1920, pledged to restore “normalcy” after World War I and the tumult of the Red scare. Summing up the Republican philosophy, Harding declared that he and his party wanted “less government in business and more business in government.” Harding’s cabinet appointments reflected this goal. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, a banker and an aluminum company titan, believed that the government should stimulate economic growth by reducing taxes on the rich, raising tariffs to protect manufacturers from foreign competition, and trimming the budget. The Republican Congress enacted much of this agenda, reducing spending and lowering inheritance and corporate taxes. During the Harding administration, tax rates for the wealthy, which had skyrocketed during World War I, plummeted from 66 percent to 20 percent. Mellon believed that those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder would prosper once business people invested the extra money they received from tax breaks into expanding production. Supposedly, the wealth would trickle down through increased jobs and purchasing power. At the same time, Republicans turned Progressive Era regulatory agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve Board into boosters for major corporations and financial institutions by weakening regulatory enforcement.

Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover had an even greater impact than Mellon in cementing the government-business partnership during the 1920s. A progressive who ably headed the Food Administration during World War I, Hoover believed that the federal government had a role to play in the economy and in lessening economic suffering. Rejecting government control of business activities, however, he insisted on voluntary cooperation between the public and private sectors. The secretary of commerce favored the creation of trade associations in which businesses would collaborate to stabilize production levels, prices, and wages. In turn, the Commerce Department would provide helpful data and information to improve productivity and trade.

Hoover’s vision fit into a larger Republican effort to weaken unions by promoting voluntary business-sponsored worker welfare initiatives. For example, under the American Plan (the name itself implied that unions were “un-American”), some firms established health insurance and pension plans for their workers. As early as 1914, Henry Ford provided his autoworkers over twenty-two years old “a share in the profits of the house” equal to a minimum wage of $5 a day, and he cut the workday from nine hours to eight hours. Already under pressure from such tactics, unions were further damaged by a series of Supreme Court rulings that restricted strikes and overturned hard-won union victories such as child labor legislation and minimum wage laws. By 1929 union membership had dropped from approximately five million to three million, or about 10 percent of the industrial labor market.

Scandals during the presidency of Warren G. Harding diminished its luster but did not tarnish the shine of Republican economic policy. The Teapot Dome scandal grabbed the most headlines. In 1921 Interior Secretary Albert Fall collaborated with Navy Secretary Edwin Denby to transfer naval oil reserves to the Interior Department. Fall then parceled out these properties to private companies. As a result, Harry F. Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Company received a lease to develop the Teapot Dome section in Wyoming. In return for this handout, Sinclair delivered more than $300,000, much of it in cash, to Fall. In the wake of congressional hearings launched by Senator Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, one of the few progressives remaining in Congress, Fall and Sinclair were convicted on a number of criminal charges and sent to jail.

Harding’s sudden death from a heart attack in August 1923 brought Vice President Calvin Coolidge to the presidency. The former Massachusetts governor, who had sent state troops to quell the Boston police strike in 1919, distanced himself from the scandals of his predecessor’s administration but reaffirmed Harding’s economic policies. “The chief business of the American people is business,” President Coolidge remarked succinctly.