Baby Boom

In 1955 Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson told the graduating class of women at Smith College that they could do their part to maintain a free society as wives and mothers. Educated women had an important role to play in maintaining a household that boosted their husband’s morale. “It is home work,” Stevenson declared. “You can do it in the living-room with a baby in your lap or in the kitchen with a can opener in your hand . . . while you’re watching television!” The mothers of these college graduates had suffered through the Great Depression, a time when the birthrate was 40 percent lower than in the 1950s. This was soon about to change.

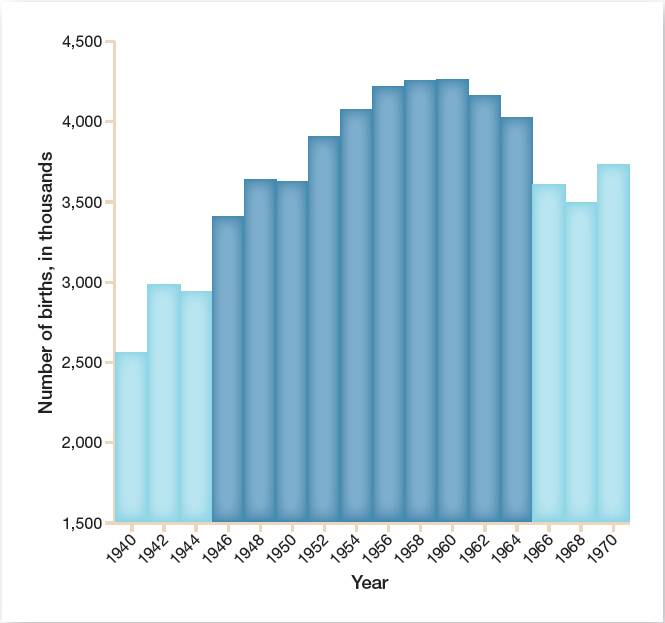

In the 1950s, the average age at marriage was younger than it had been in the 1930s. On average, men married for the first time at the age of just under twenty-three, and49 percent of women married at nineteen. Couples also produced children at an astonishing rate. In the 1950s, the growth rate in the U.S. population approached that of India, a country with one of the highest birthrates in the world (Figure 25.2).

Marriage and parenthood reflected a culture that increasingly emphasized early marriages and large families. The Cold War spurred this development. In the Atomic Age, public officials and the media urged young American men and women to build nuclear families in which the father held a paying job and the mother stayed at home and raised her growing family. Doing so would strengthen the moral fiber of the United States in its battle to contain Soviet communism. Religious leaders echoed this message. “The family that prays together stays together” became a popular refrain and served as an inducement to encourage marital fertility alongside spiritual fidelity.

Parents could also look forward to their children surviving childhood diseases that had resulted in many childhood deaths in the past. In the 1950s, children received vaccinations against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tuberculosis before they entered school. The most serious illness affecting young children remained the crippling disease of polio, or infantile paralysis. Each year, usually around summertime, parents and children feared a renewed outbreak of the polio virus, which they believed was spread through contact at crowded swimming pools and beaches. An outbreak of polio in 1952 and 1953 infected 93,000 people nationwide. In 1955 Dr. Jonas Salk developed a successful injectable vaccine against the disease. On April 12, 1955, news bulletins interrupted scheduled television programs to announce Salk’s breakthrough, and, as one writer recalled, “citizens rushed to ring church bells and fire sirens, shouted, clapped, sang, and made every kind of joyous noise they could.” Dr. Albert Sabin later developed a more convenient oral vaccine, and by the mid-1960s polio was no longer a public health menace in the United States.