Freedom Summer and Voting Rights

Following Kennedy’s death and three months after the March on Washington, President Johnson took charge of the pending civil rights legislation. Under Johnson’s leadership, a bipartisan coalition turned back a southern filibuster (a tactic that delays or prevents action in Congress) in the Senate and passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law prohibited discrimination in public accommodations, increased federal enforcement of school desegregation and the right to vote, and created the Community Relations Service, a federal agency authorized to help resolve racial conflicts. The act also contained a final measure to combat employment discrimination on the basis of race and sex.

Yet even as President Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, black freedom forces launched a new offensive to secure the right to vote in the South. The 1964 act contained a voting rights provision but did little to address the main problems of the discriminatory use of literacy tests and poll taxes and the biased administration of voter registration procedures that kept the majority of southern blacks from voting. Three years earlier, the Kennedy administration had brokered a deal to secure private funding for voter registration drives in the South directed by the Atlanta-based Voter Education Project. Civil rights workers believed that the Justice Department would provide federal protection for voter drives, but the Kennedy and Johnson administrations let them down. Beatings, killings, arson, and arrests became a routine response to voting rights efforts. Although the Justice Department filed lawsuits against recalcitrant voter registrars and police officers, the government refused to send in federal personnel or instruct the FBI to safeguard vulnerable civil rights workers.

To focus national attention on this problem, SNCC, CORE, the NAACP, and the SCLC launched the Freedom Summer project in Mississippi. They assigned eight hundred volunteers from around the nation, mainly white college students, to work on voter registration drives and in “freedom schools” to improve education for rural black youngsters stuck in inferior, segregated schools. White supremacists fought back against what they perceived as an enemy invasion. In late June 1964, the Ku Klux Klan, in collusion with local law enforcement officials, killed three civil rights workers. This tragedy brought national attention, and President Johnson pressed the usually uncooperative FBI to find the culprits, which it did. However, civil rights workers continued to encounter white violence and harassment throughout Freedom Summer. See Document Project 26: Freedom Summer.

One outcome of the Freedom Summer project was the creation of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). Because the regular all-white state Democratic Party excluded blacks, the civil rights coalition formed an alternative Democratic Party open to everyone. In August 1964, the mostly black MFDP sent a delegation to the Democratic National Convention meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to challenge the seating of the all-white delegation from Mississippi. One of the MFDP delegates, Fannie Lou Hamer, who had lost her job on a Mississippi plantation for her voter registration activities, offered passionate testimony broadcast on television. To avoid a bruising political fight, Johnson hammered out a compromise that gave the MFDP two general at-large seats, imposed a loyalty oath on members of the regular delegation to support the Democratic presidential ticket, and prohibited racial discrimination in the future by any state Democratic Party. Although both sides rejected the compromise, four years later an integrated delegation, which included Hamer, represented Mississippi at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Freedom Summer highlighted the problem of disfranchisement, but it took further demonstrations in Selma, Alabama, to resolve it. After state troopers shot and killed a black voting rights demonstrator in February 1965, Dr. King called for a march from Selma to the capital of Montgomery to petition Governor George Wallace to end the violence and allow blacks to vote. Local law enforcement officials answered their peaceful protests with arrests and beatings. On Sunday, March 7, as black and white marchers left Selma, the sheriff’s forces sprayed them with tear gas, beat them, and sent them running for their lives back to town. A few days later, a white clergyman who had joined the protesters was killed on the streets of Selma by a group of white thugs. On March 21, following another failed attempt to march to Montgomery, King led protesters on the fifty-mile hike to the state capital, where they arrived safely four days later. Tragically, after the march, the Ku Klux Klan murdered a white female marcher from Michigan.

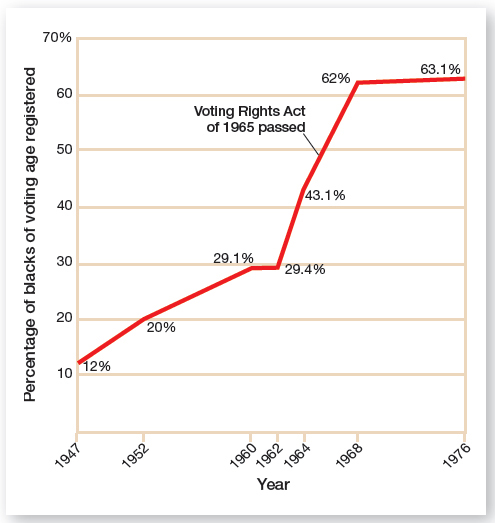

Events in Selma prompted President Johnson to take action. On March 15, he addressed a joint session of Congress and told lawmakers and a nationally televised audience that the black “cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.” In the words of the civil rights movement anthem, Johnson added, “And we shall overcome.” On August 6, 1965, the president signed the Voting Rights Act, which banned the use of literacy tests for voter registration, authorized a federal lawsuit against the poll tax (which succeeded in 1966), empowered federal officials to register disfranchised voters, and required seven southern states to submit any voting changes to Washington before they went into effect. With strong federal enforcement of the law, by 1968 a majority of African Americans and nearly two-thirds of black Mississippians could vote in the South (Figure 26.1).

Review & Relate

|

What role did the federal government play in advancing the cause of racial equality in the early 1960s? |

How did civil rights activists pressure state and federal government officials to enact their agenda? |