Movements on the Left

The civil rights movement had inspired many young people to activism. Combining ideals of freedom, equality, and community with direct-action protest, civil rights activists offered a model for those seeking to address a variety of problems, including the Cold War threat of nuclear devastation, the loss of individual autonomy in a corporate society, racism, poverty, sexism, and the poisoning of the environment. The formation of SNCC in 1960 illuminated the possibilities for personal and social transformation and offered a movement culture founded on democracy.

Tom Hayden helped apply the ideals of SNCC to predominantly white college campuses. After spending the summer of 1961 registering voters in Mississippi and Georgia, the University of Michigan graduate student returned to campus eager to recruit like-minded students who questioned America’s commitment to democracy. “Beyond lunch counter demonstrations,” Hayden wrote, “there are more serious evils which must be ripped out by any means: exploitation, socially destructive capital, evil political and legal structure, and myopic liberalism which is anti-revolutionary.”

Hayden became an influential leader of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which advocated the formation of a “New Left.” They considered the “Old Left,” which revolved around the Communist Party, as autocratic and no longer relevant. In its Port Huron Statement (1962), SDS condemned mainstream liberal politics, Cold War foreign policy, racism, and research-oriented universities that cared little for their undergraduates. It called for the adoption of “participatory democracy,” which would return power to the people. SDS argued that the age of the military-industrial complex, with its mega-universities and giant corporations, had created a new educated class of alienated white-collar workers and college students perfectly suited to lead the revolution.

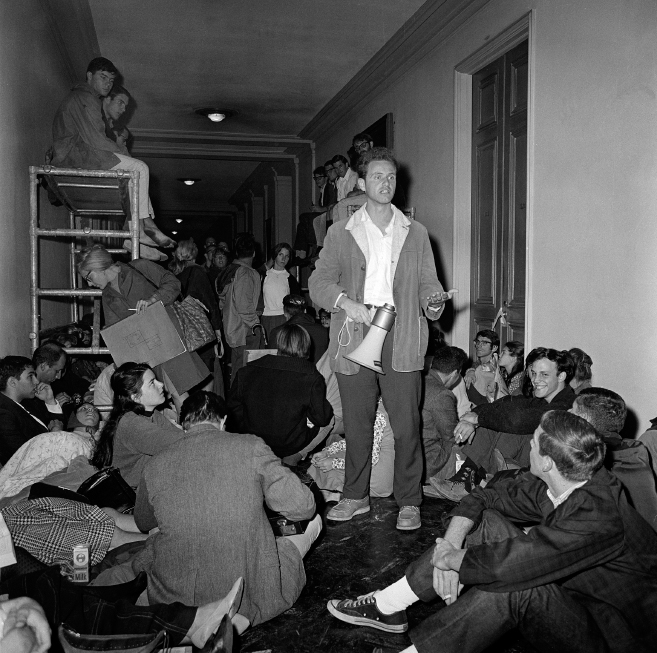

The New Left never consisted of one central organization such as SDS; after all, many protesters challenged the very idea of centralized authority. In fact, SDS did not initiate the New Left’s most dramatic, early protest. In 1964 the University of California at Berkeley banned political activities just outside the main campus entrance in response to CORE protests against racial bias in local hiring. When CORE defied the prohibition, campus police arrested its leader, prompting a massive student uprising. The university’s prohibition also spurred students to form the Free Speech Movement (FSM), which held rallies in front of the administration building, culminating in a nonviolent, civil rights–style sit-in to assert their right to participate in such activities. When California governor Edmund “Pat” Brown dispatched a large force of state and county police to evict the demonstrators, students and faculty joined together in protest and forced the university administration to yield to FSM’s demands for amnesty and reform. By the end of the decade, hundreds of demonstrations had erupted on campuses throughout the nation, culminating in 1968 in a bloody confrontation at Columbia University between students and New York City police. Unlike protests in the South aimed at reactionary white supremacists, campus revolts targeted liberals, dismissing them as obstacles to genuine social change.

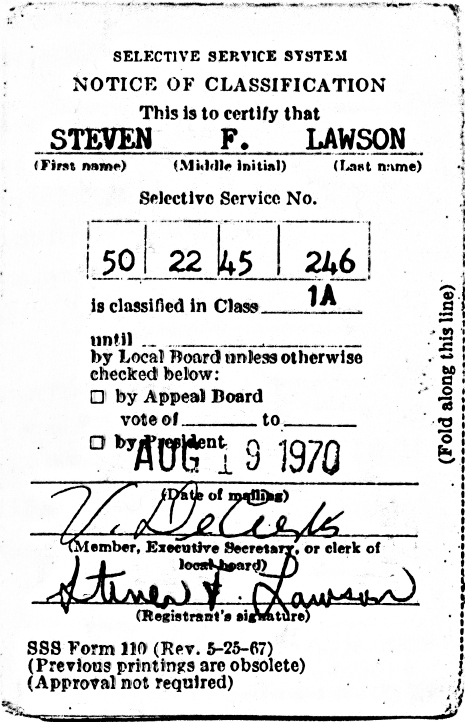

The Vietnam War accelerated student radicalism, and college campuses provided a strategic setting for antiwar activities. Like most Americans in the mid-1960s, undergraduates had only a dim awareness of U.S. activity in Vietnam. Yet all college men were eligible for the draft once they graduated and lost their student deferment. As more troops were sent to Vietnam, student concern intensified.

Protests escalated in 1966 as President Johnson authorized an additional 250,000-troop buildup in Vietnam. This mobilization required higher draft calls, which began to affect more college men. With induction into the military a looming possibility, student protesters engaged in a variety of activities. Some burned draft cards; disrupted attempts by outside firms, such as the CIA and Dow Chemical Company (which made napalm), to recruit on campus; or campaigned against the presence on campus of Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), which prepared future military leaders. Others resisted the draft by fleeing to Canada, and still others engaged in various forms of civil disobedience. Most college students, however, were not activists—between 1965 and 1968, only 20 percent of college students attended demonstrations. Nevertheless, the activist minority received wide media attention and helped raise awareness about the difficulty of waging the Vietnam War abroad and maintaining domestic tranquillity at home.

By the end of 1967, as the number of troops in Vietnam approached half a million, protests increased. Antiwar sentiment had spread to faculty, artists, writers, business people, and elected officials. Earlier that year in April, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a powerful antiwar address at Riverside Church in New York City. “The world now demands,” King declared, “. . . that we admit that we have been wrong from the beginning of our adventure in Vietnam, that we have been detrimental to the life of the Vietnamese people.” In 1968 SDS split into factions, with the most prominent of them, the Weathermen, going underground and adopting violent tactics.

The New Left’s challenge to liberal politics attracted many students, and the counterculture’s rejection of conventional middle-class values of work, sexual restraint, and faith in reason captivated even more. Cultural rebels emphasized living in the present, immediate gratification, authenticity of feelings, and reaching a higher consciousness through mind-altering drugs like marijuana and LSD. These youth rebels, popularly called “hippies,” mocked their elders in the slogan “Don’t trust anyone over thirty.” Despite differences in approach, both the New Left and the counterculture expressed concerns about modern technology, bureaucratization, and the possibility of nuclear annihilation and sought new means of creating political, social, and personal liberation.

Rock ’n’ roll became the soundtrack of the counterculture. In 1964 Bob Dylan’s song “The Times They Are A-Changin’” became an anthem for youth rebellion, just as his “Blowin’ in the Wind” did for the civil rights movement. In 1964 the Beatles, a British quartet influenced by 1950s black and white rock ’n’ rollers, came to the United States and revolutionized popular music. Originally singing tuneful compositions of teenage love and angst, the Beatles embraced the counterculture and began writing songs about alienation and politics, flavoring them with the drug-inspired sounds of psychedelic music. The Beatles launched a “British invasion,” which also brought the Rolling Stones, who offered a harder-edged and raunchier sound than did the Beatles. Although most of the songs that reached the top ten on the record charts did not undermine traditional values, the music of groups like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and the Doors spread counterculture messages of youth rebellion. At the same time, young black and white rebels embraced “soul music,” black dance music popularized through the African American–owned Motown Records in Detroit and the white-owned Stax Records in Memphis.

The counterculture viewed the elimination of sexual restrictions as essential for transforming personal and social behavior. The 1960s generation did not invent sexual freedom, but it did a great deal to shatter time-honored moral codes of monogamy, fidelity, and moderation. Promiscuity—casual sex, group sex, extramarital affairs, public nudity—and open-throated vulgarity tested public tolerance. Yet within limits, the popular culture reflected these changes. The Broadway production of the musical Hair showed frontal nudity, the movie industry adopted ratings of “X” and “R” that made films with nudity and profane language available to a wider audience, and new television comedy shows featured sketches including risqué content and double entendres. With a nod from the Warren Court’s easing definitions of pornography, counterculture writers assaulted the boundaries of “good taste.”

With sexual conduct in flux, society had difficulty maintaining the double standard of behavior that privileged men over women. The counterculture gave many women a chance to pursue and enjoy sexual pleasure that had long been denied to them. The availability of birth control pills for women, introduced in 1960, made much of this sexual freedom possible. Although sexual liberation still carried more risks for women than for men, increased openness in discussing sexuality allowed many women to gain greater control over their bodies and their relationships.