Fighting International Terrorism

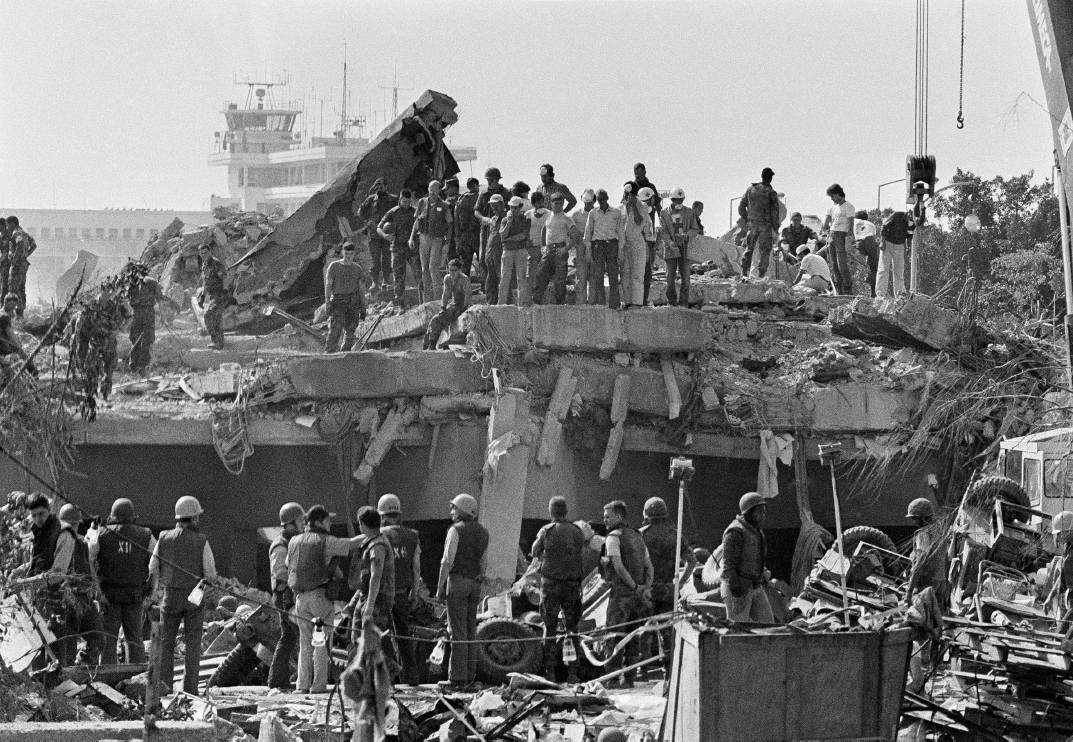

Two days before the Grenada invasion in 1983, the U.S. military suffered a grievous blow halfway around the world. In the tiny country of Lebanon, wedged between Syrian occupation on its northern border and the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) fight against Israel to the south, a civil war raged between Christians and Muslims. Reagan believed that stability in the region was in America’s national interest. With this in mind, in 1982 the Reagan administration sent 800 marines, as part of a multilateral force that included French and Italian troops, to keep the peace, but fighting continued in Beirut between Christian and Muslim militias. On October 23, 1983, a suicide bomber drove a truck into a marine barracks, killing 241 soldiers. Reagan withdrew the remaining troops.

The removal of troops did not end threats to Americans in the Middle East. Terrorism had become an ever-present danger, especially since the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979–1980. In 1985, 17 American citizens were killed in terrorist assaults, and 154 were injured. In June 1985, Shi’ite Muslim extremists hijacked a TWA airliner in Athens with 39 Americans on board and flew it to Beirut. The Israeli government acceded to the hijackers’ demands to release Shi’ite prisoners in its jails, and the crisis ended safely for the hostages. That same year, PLO members hijacked an Italian cruise ship in the Mediterranean. Before the dangerous situation was resolved, an elderly American man in a wheelchair was killed and his body dumped in the sea.

In response, the Reagan administration targeted the North African country of Libya for retaliation. Its military leader, Muammar al-Qaddafi, supported the Palestinian cause and provided sanctuary for terrorists. In 1981 a squadron of Libyan planes attacked a U.S. naval flotilla conducting maneuvers off Libyan shores, and American pilots shot down two enemy planes. The Reagan administration placed a trade embargo on Libya, and Secretary of State Shultz remarked: “We have to put Qaddafi in a box and close the lid.” In 1986, after the bombing of a nightclub in West Berlin killed 2 American servicemen and injured 230, Reagan charged that Qaddafi was responsible. In late April, the United States retaliated by sending planes to bomb the Libyan capital of Tripoli. The military strongman survived, but one of his daughters perished in the attack. Following the bombing, Qaddafi took a much lower profile against the United States. Reagan had demonstrated his nation’s military might despite the retreat in Lebanon (Map 28.1).

The Reagan administration’s efforts to fight communism in Central America and terrorism in the Middle East continued unabated. Despite passage of the Boland Amendment in 1982 and its extension in 1984, the president continued to support the Nicaraguan Contras. By 1985 the Contras numbered somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 troops and relied almost entirely on U.S. assistance. Barred from providing direct military or economic aid to the Contras, Reagan ordered the CIA and the National Security Council (NSC) to raise money from anti-Communist leaders abroad and wealthy conservatives at home. This effort, called “Project Democracy,” raised millions of dollars. In violation of federal law, CIA director William Casey also authorized his agency to continue training the Contras in assassination techniques and other methods of subversion.

In the meantime, the situation in Lebanon remained critical as the strife caused by civil war led to the seizing of American hostages. By mid-1984, seven Americans, including the CIA bureau chief in Beirut, had been kidnapped by Shi’ite Muslims financed by Iran. Since 1980, Iran, a Shi’ite nation, had been engaged in a protracted war with Iraq, which was ruled by military leader Saddam Hussein and his Sunni Muslim party, the chief rival to the Shi’ites. With relations between the United States and Iran having deteriorated in the aftermath of the 1979 coup, the Reagan administration backed Iraq in this war. The fate of the hostages, however, motivated Reagan to make a deal with Iran. In late 1985, Reagan’s national security adviser Robert McFarlane negotiated secretly with an Iranian intermediary for the United States to sell antitank missiles to Iran in exchange for the Shi’ite government using its influence to induce the Muslim kidnappers to release the hostages. This covert bargain produced mixed success. Two Americans were freed by the end of 1986, but by then another three had been captured.

Had the matter ended there, the secret deal might never have come to light. However, NSC aide Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North developed a plan to transfer the proceeds from the arms-for-hostages deal to fund the Contras and circumvent the Boland Amendment. Despite opposition from Secretary of State Shultz, Reagan liked North’s plan, although the president seemed vague about the details, and some $10 million to $20 million of Iranian money flowed into the hands of the Contras.

In 1986 information about the Iran-Contra connection came to light. See Document Project 28: The Iran-Contra Scandal. Not since the Watergate scandal had a presidential administration received such intense media scrutiny. In the summer of 1987, televised Senate hearings exposed much of the tangled, covert dealings with Iran. In 1988 a special federal prosecutor indicted NSC adviser Vice Admiral John Poindexter (who had replaced McFarlane), North, and several others on charges ranging from perjury to conspiracy to obstruct justice. However, Reagan did not suffer the same fate or disgrace as had Nixon. Certainly the president knew what had been going on and had even approved it, but what he said publicly about his responsibility was circumscribed: “A few months ago, I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and best intentions still tell me that is true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.”