The English Establish Jamestown

England’s success in colonizing North America depended in part on a new economic model in which investors sold shares in joint-stock companies and sought royal support for their venture. In 1606 a group of London merchants formed the Virginia Company, and King James I granted them the right to settle a vast area of North America, from present-day New York to North Carolina. The proprietors promised to “propagate the Christian religion” among native inhabitants in the region, but they were far more interested in turning a profit.

Most of the men that the Virginia Company recruited as colonists were, like John Smith, adventurers who hoped to get rich through the discovery of precious metals. Arriving on the coast of North America in April 1607 after a four-month voyage, the weary colonists established Jamestown on a site they chose for its easy defense. Although bothered by the settlement’s mosquito-infested environment, the colonists focused their energies on the search for gold and silver.

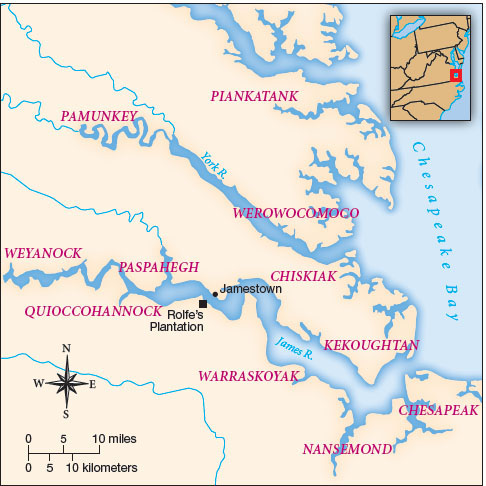

The Englishmen also made contact with the Indian chief Powhatan, who presided over a confederation of some 14,000 Algonquian-speaking Indians from 25 to 30 tribes. The Powhatan Confederacy was far more powerful than its English neighbors, and, indeed, for the first two years the settlers depended on the Indians to survive. Although the Jamestown settlers were often hungry, few of them engaged in farming. Moreover, the nearby water was tainted by salt from the ocean, and diseases that festered in the low-lying area ensured a high death toll. Nine months after arriving in Virginia, only 38 of the original 105 settlers remained alive.

Despite the Englishmen’s aggressive posture and inability to feed themselves, Powhatan initially assisted the settlers in hopes they could provide him with English cloth, iron hatchets, and even guns. His capture and subsequent release of John Smith in 1607 suggests his interest in developing trade relations with the newcomers even as he sought to subordinate them. But leaders like Captain Smith considered Powhatan and his warriors a threat rather than an asset. Although Jamestown residents could not afford to engage in open hostilities with local natives, they did raid villages for corn and other food, making Powhatan increasingly wary. The settlers’ decision to construct a fort under Smith’s direction only increased the Indians’ concern.

Meanwhile the Virginia Company devised a new plan to stave off the collapse of its colony. It started selling seven-year joint-stock options to raise funds and recruited new settlers to produce staple crops—grapes, sugar, cotton, or tobacco—for export since the search for precious metals had failed. Interested individuals who could not afford to invest cash could sign on for service in Virginia. After seven years, these colonists would receive a hundred acres of land. In June 1609, a new contingent of colonists attracted by this plan—five hundred men and a hundred women—sailed for Jamestown (Map 2.1).

The new arrivals, however, had not brought enough supplies to sustain the colony through the winter. Powhatan did offer some aid, but a severe dry spell meant that the Indians, too, suffered from shortages in the winter of 1609–1610. A “starving time” settled on Jamestown. By the spring of 1610, seven of every eight settlers who had arrived in Jamestown since 1607 were dead. One colonist noted that settlers “were destroyed by cruell diseases, as Swellings, Fluxes, [and] Burning Fevers,” though most “died of mere famine.”

That June, the sixty survivors decided to abandon Jamestown and sail for home. But in the harbor, they met three English ships loaded with supplies and three hundred more settlers. Fresh supplies and a larger population inspired the English to take a much more confrontational approach. Jamestown’s new leaders adopted an aggressive military posture, attacking native villages, burning crops, killing many Indians, and taking others captive. They believed that such brutality would horrify neighboring tribes and convince them to obey English demands for food and labor.