Expansion, Rebellion, and the Emergence of Slavery

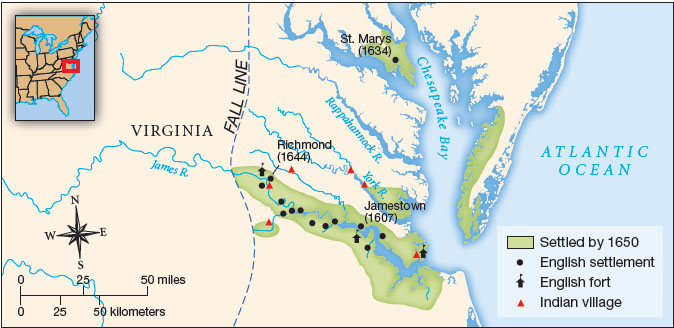

By the 1630s, despite continued conflicts with Indians, Virginia was well on its way to commercial success. The most successful tobacco planters utilized indentured servants, including some Africans as well as thousands of English and Irish immigrants. Between 1640 and 1670, some 40,000 to 50,000 of these migrants settled in Virginia and neighboring Maryland (Map 2.2). Maryland was founded in 1632 when King Charles I, the successor to James I, granted most of the territory north of Chesapeake Bay and the title of Lord Baltimore to Cecilius Calvert. Calvert was among the minority of English who remained a Catholic, and he planned to create Maryland as a refuge for his persecuted coworshippers. Appointing his brother Leonard Calvert as governor, he carefully prepared for the first settlement. The Calverts recruited skilled artisans and farmers (mainly Protestant) as well as wealthy merchants and aristocrats (mostly Catholic) to establish St. Mary’s City on the mouth of the Potomac River. Although conflict continued to fester between the Catholic elite and the Protestant majority, Governor Calvert convinced the Maryland assembly to pass the Act of Religious Toleration in 1649, granting religious freedom to all Christians.

Taken together, Maryland and Virginia formed the Chesapeake region of the English empire. Both colonies relied on tobacco to produce the wealth that fueled their growth, and both introduced African labor to complement the supply of white indentured servants. This proved especially important from 1650 on, as improved economic conditions in England meant fewer English men and women were willing to gamble on a better life in North America. Although the number of African laborers remained small until late in the century, there was a growing effort on the part of colonial leaders to increase their control over this segment of the workforce. Thus in 1660 the House of Burgesses passed an act that allowed African laborers to be enslaved. In 1664 Maryland followed suit. A slow if unsteady march toward full-blown racial slavery had begun.

Explore

See Document 2.4 for the Virginia law that made slavery an inherited condition passed from mother to child.

In legalizing human bondage, Virginia legislators followed a model established in Barbados, where the booming sugar industry spurred the development of plantation slavery. By 1660 Barbados had become the first English colony with a black majority population. Twenty years later, there were seventeen slaves for every white indentured servant on Barbados. The growth of slavery on the island depended almost wholly on imports from Africa since slaves there died faster than they could reproduce themselves. In the context of high death rates, brutal working conditions, and massive imports, Barbados systematized its slave code, defining enslaved Africans as chattel—that is, as mere property more akin to livestock than to human beings. Slaves existed to enrich their masters, and masters could do with them as they liked.

While African slaves would, in time, become a crucial component of the Chesapeake labor force, indentured servants made up the majority of bound workers in Virginia and Maryland for most of the seventeenth century. They labored under harsh conditions, and punishment for even minor infractions could be severe. Servants had holes bored in their tongues for complaining against their masters; they were beaten, whipped, and branded for a variety of “crimes”; and female servants who became pregnant had two years added to their contracts. Some white servants made common cause with black laborers who worked side by side with them on tobacco plantations. They ran away together, stole goods from their masters, and planned uprisings and rebellions.

By the 1660s and 1670s, the population of former servants who had become free formed a growing and increasingly unhappy class. Most were struggling economically, working as common laborers or tenants on large estates. Those who managed to move west and claim land on the frontier were confronted by hostile Indians like the Susquehannock. Virginia governor Sir William Berkeley had little patience with the complaints of these colonists. The labor demands of wealthy tobacco planters needed to be met, and frontier settlers’ call for an aggressive Indian policy would hurt the profitable deerskin trade with the Algonquian Indians. Adopting a defensive strategy, Berkeley maintained a system of nine forts along the frontier that was supported by taxes, providing another aggravation for poorer colonists.

In late 1675, conflict erupted when frontier settlers attacked not the Susquehannock nation but rather Indian communities allied with the English since 1646. An even larger force of Virginia militiamen then surrounded a Susquehannock village and murdered five chiefs who tried to negotiate for peace. Susquehannock warriors retaliated with deadly raids on frontier farms. Despite the outbreak of open warfare, Governor Berkeley still refused to send troops, so disgruntled farmers turned to Nathaniel Bacon. Bacon, only twenty-nine years old and a newcomer to Virginia, came from a wealthy family and was related to Berkeley by marriage. But he defied the governor’s authority and called up an army to attack all of the region’s Indians, whether Susquehannocks or English allies. Bacon’s Rebellion had begun. Frontier farmers formed an important part of Bacon’s coalition. But affluent planters who had been left out of Berkeley’s inner circle also joined Bacon in hopes of gaining access to power and profits. And bound laborers, black and white, assumed that anyone who opposed the governor was on their side.

In the summer of 1676, Governor Berkeley declared Bacon guilty of treason. Rather than waiting to be captured, Bacon led his army toward Jamestown. Berkeley then arranged a hastily called election to undercut the rebellion. Even though Berkeley had rescinded the right of men without property to vote, Bacon’s supporters won control of the House of Burgesses, and Bacon won new adherents. These included “news wives,” lower-class women who spread information (and rumors) about oppressive conditions, thereby aiding the rebels. As Bacon and his followers marched across Virginia, his men plundered the plantations of Berkeley supporters and captured Berkeley’s estate at Green Spring. In September they reached Jamestown after the governor and his administration fled across Chesapeake Bay. The rebels burned the capital to the ground, victory seemingly theirs.

Only a month later, however, Bacon died of dysentery, and the movement he formed unraveled. Governor Berkeley, with the aid of armed ships from England, quickly reclaimed power. Outraged by the rebellion, he hanged twenty-three rebel leaders and incited his followers to plunder the estates of planters who had supported Bacon. But he could not undo the damage to Indian relations on the Virginia frontier. Bacon’s army had killed or enslaved hundreds of once-friendly Indians and left behind a tragic and bitter legacy.

An even more important consequence of the rebellion was that wealthy planters and investors realized the depth of frustration among poor white men and women who were willing to make common cause with their black counterparts. Having regained power, the planter elite worked to crush any such interracial alliance. They promised most white rebels who put down arms the right to return home peacefully, and most complied. Virginia legislators then began to improve the conditions and rights of poorer white settlers while imposing new restrictions on blacks. At nearly the same time, in an effort to meet the growing demand for labor in the West Indies and the Chesapeake, King Charles II chartered the Royal African Company in 1672 to carry enslaved women and men from Africa to North America.