The Atlantic Slave Trade

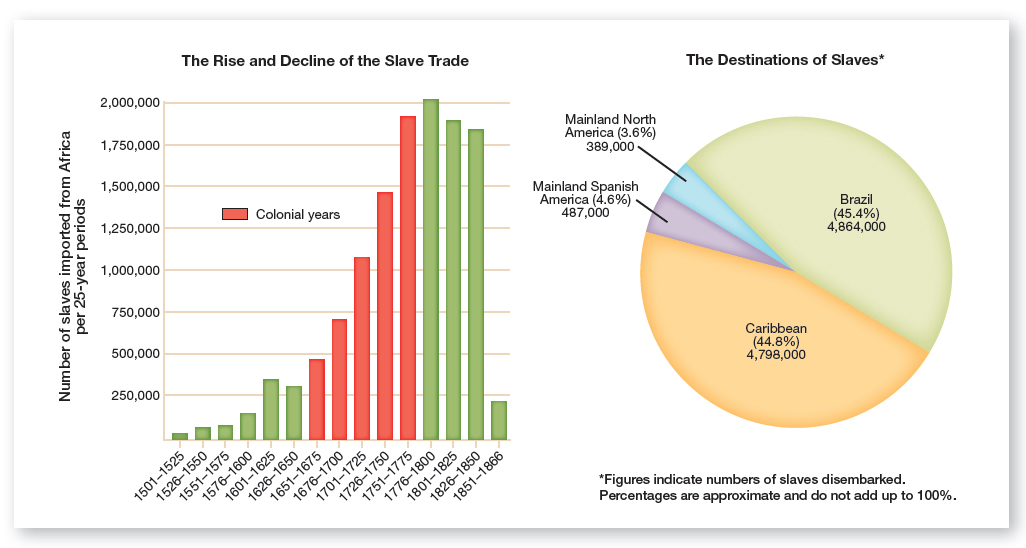

Parliament chartered the Royal African Company in 1672, and England slowly expanded its role in the slave trade as the Dutch commercial empire waned. In 1713, when the British gained the right to sell slaves to Spanish colonies, that nation became a major player in the horrific trade in human cargo. Between 1700 and 1808, some 3 million captive Africans were carried on British and Anglo-American ships, about 40 percent of the total of those sold in the Americas in this period (Figure 3.1). Half a million Africans died on the voyage across the Atlantic. Huge numbers also died in Africa, while being marched to the coast or held in forts waiting to be forced aboard ships. Yet despite this astounding death rate, the slave trade yielded enormous profits and had far-reaching consequences: The Africans that British traders bought and sold transformed labor systems in the colonies, fueled international trade, and enriched merchants, planters, and their families and partners. See e-Document Project 3: The African Slave Trade.

European traders worked closely with African merchants to gain their human cargo. Where once they had traded textiles and alcohol for gold and ivory, Europeans now traded muskets, metalware, and linen for men, women, and children. Originally many of those sold into slavery were war captives. But by the time British and Anglo-American merchants became central to this notorious trade, their contacts in Africa were procuring labor in any way they could. The cargo included war captives, servants, and people snatched in raids specifically to secure slaves. Over time, African traders moved farther inland to fill the demand, devastating large areas of West Africa, particularly the Congo-Angola region, which supplied some 40 percent of all Atlantic slaves.

The trip across the Atlantic, known as the Middle Passage, was a brutal and often deadly experience for Africans. Exhausted and undernourished by the time they boarded the large oceangoing vessels, the captives were placed in dark and crowded holds. Most had been poked and prodded by slave traders, and some had been branded to ensure that a trader received the exact individuals he had purchased. Once in the hold, they might wait for weeks before the ship finally set sail. By that time, the foul-smelling and crowded hold became a nightmare of disease and despair. There was never sufficient food or fresh water for the captives, and women especially were subject to sexual abuse and rape by crew members. Many captives could not communicate with each other since they spoke different languages, and none of them knew exactly where they were going or what would happen when they arrived.

Explore

See Document 3.3 for a look inside a slave ship.

Those who survived the voyage were likely to find themselves in the slave markets of Barbados or Jamaica, where they were put on display for potential buyers. Once purchased, the slaves went through a period of seasoning as they regained their strength, became accustomed to their new environment, and learned commands in a new language. In this period of acculturation, enslaved laborers also confronted strange foods, new diseases, and unfamiliar tasks. Most were also given new names. Some did not survive seasoning, falling prey to malnutrition and disease or committing suicide. Others adapted to the new circumstances and adopted enough European or British ways to carry on even as they sought means to resist the shocking and oppressive conditions.

More than half of the slaves imported to the Lower South entered the mainland at Charleston, South Carolina. Beginning around 1700, enslaved Africans were shipped directly to Charleston rather than transshipped from the West Indies. Successful planters like Eliza Lucas likely had first choice of the new arrivals, sending agents to the wharves to buy Africans.