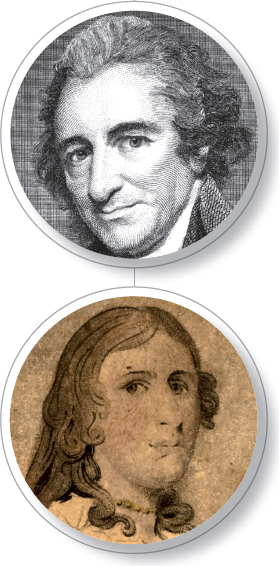

American Histories: Thomas Paine and Deborah Sampson

AMERICAN HISTORIES

On November 30, 1774, Thomas Paine arrived in Philadelphia aboard a ship from London. At age thirty-seven, Paine had failed at several occupations and two marriages. But he was an impassioned writer. A pamphlet he wrote caught the eye of Benjamin Franklin, who helped him secure a job on The Pennsylvania Magazine just as tensions between the colonies and Great Britain neared open conflict.

Born in 1737, Paine was raised in an English market town by parents who owned a small grocery store and made whalebone corsets. The Paines managed to send him to school for a few years before his father introduced him to the trade of corset-making. Over the next dozen years, Paine also worked as a seaman, a preacher, a teacher, and an excise (or tax) collector. He drank heavily and beat both his wives. Yet despite his personal vices, Paine tried to improve himself and the lot of other British workers. He taught working-class children how to read and write and attended lectures on science and politics in London. As an excise collector in 1762, he wrote a pamphlet that argued for better pay and working conditions for tax collectors. He was fired from his job, but Franklin convinced Paine to try his luck in Philadelphia.

Paine quickly gained in-depth political knowledge of the conflicts between the colonies and Great Britain and gained patrons among Philadelphia’s economic and political elite. When armed conflict with British troops erupted in April 1775, colonial debates over whether to declare independence intensified. Pamphlets were a popular means of influencing these debates, and Paine hoped to write one that would tip the balance in favor of independence. In January 1776, his pamphlet Common Sense did just that.

An instant success, Common Sense provided a rationale for independence and an emotional plea for creating a new democratic republic. Paine urged colonists not only to separate from England but also to establish a political structure that would ensure liberty and equality for all Americans: “A government of our own is our natural right,” he concluded. “ ’Tis time to part.”

When Common Sense was published in 1776, sixteen-year-old Deborah Sampson was working as a servant to Jeremiah and Susanna Thomas in Marlborough, Massachusetts. Indentured at the age of ten, she looked after the Thomases’ five sons and worked hard in both the house and the fields. Jeremiah Thomas thought education was above the lot of servant girls, but Sampson insisted on reading whatever books she could find. However, her commitment to American independence likely developed less from reading and more from the fighting that raged in Massachusetts and drew male servants and the Thomas sons into the Continental Army in the 1770s.

When Deborah Sampson’s term of service ended in 1778, she sought work as a weaver and then a teacher. In March 1782, she disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the Continental Army, which was then desperate for recruits. Her height and muscular frame allowed her to fool local recruiters, and she accepted the bounty paid to those who enlisted. But Deborah never reported for duty, and when her charade was discovered, she was forced to return the money.

In May 1782, Sampson enlisted a second time under the name Robert Shurtliff. To explain the absence of facial hair, she told the recruiter that she was only seventeen years old. For the next year, Sampson, disguised as Shurt-liff, marched, fought, and lived with her Massachusetts regiment. Her ability to carry off the deception was helped by lax standards of hygiene: Soldiers rarely undressed fully to bathe, and most slept in their uniforms.

Even after the formal end of the war in March 1783, Sampson/Shurtliff continued to serve in the Continental Army. In the fall of 1783, she was sent to Philadelphia to help quash a mutiny by Continental soldiers angered over the army’s failure to provide back pay. While there, Sampson/Shurtliff fell ill with a raging fever, and a doctor at a local army hospital discovered that “he” was a woman. He reported the news to General John Paterson, and Sampson was honorably discharged, having served the army faithfully for more than a year. •

AS THE AMERICAN HISTORIES of Thomas Paine and Deborah Sampson demonstrate, the American Revolution transformed individual lives as well as the political life of the nation. Paine had failed financially and personally in England but gained fame in the colonies through his skills as a patriot pamphleteer. Sampson, who was forced into an early independence by her troubled family, excelled as a soldier. Still, while the American Revolution offered opportunities for some colonists, it promised hardship for others. Most Americans had to choose sides long before it was clear whether the colonists could defeat Great Britain, and the long years of conflict (1775–1783) took a toll on families and communities across the thirteen colonies. Over the course of a long and difficult war, could the patriots attract enough Tom Paines and Deborah Sampsons to secure independence and establish a new nation?