Technology Reshapes Agriculture and Industry

Advances in agricultural and industrial technology paralleled the development of roads and steamboats. Here, too, a single invention spurred others, inducing a multiplier effect that inspired additional dramatic changes during the decades following the Revolution. Two inventions—the cotton gin and the spinning machine—were especially notable in transforming southern agriculture and northern industry, transformations that were deeply intertwined.

American developments were also closely tied to the earlier rise of industry in Great Britain. By the 1770s, British manufacturers had built spinning mills in which steam-powered machines spun raw cotton into yarn. Importing cotton from Britain’s colonies, British manufacturers thrived. Eager to maintain their monopoly on industrial technology, the British made it illegal for engineers to emigrate. They could not, however, keep everyone who worked in a cotton mill from leaving the country. At age fourteen, Samuel Slater was hired as an apprentice in an English mill that used a yarn-spinning machine designed by Richard Arkwright. Slater was promoted to supervisor of the factory, but at age twenty-one he sought greater opportunities in America. While working in New York City, he learned that Moses Brown, a wealthy Rhode Island merchant, was seeking help in developing a machine like Arkwright’s. Funded by Rhode Island investors and assisted by local craftsmen, Slater designed and built a spinning mill in Pawtucket.

The mill opened in December 1790 and began producing yarn, which was then woven into cloth in private shops and homes. By 1815 a series of cotton mills, most built to look like New England meetinghouses in order to limit hostility from local farmers, dotted the Pawtucket River. These factories promised a steady income for workers in the mills, most of whom were the wives and children of farmers, and ensured employment for weavers in the countryside. They also increased the demand for cotton in New England just as British manufacturers sought new sources of the crop as well.

Ensuring a steady supply of cotton, however, required another technological innovation, this one created by Eli Whitney. After graduating from Yale at age twenty-seven, Whitney agreed to serve as a private tutor for a planter family in South Carolina. On the ship carrying him to his new position, Whitney met Catherine Greene, widow of the Revolutionary War general Nathanael Greene. He ended up staying on her Mulberry Plantation near Savannah, Georgia, where local planters complained to him about the difficulty of making a profit on cotton in the area. Long-staple cotton, grown in the Sea Islands, yielded enormous profits, but the soil in most of the South could sustain only the short-staple variety, which required hours of intensive labor to separate its sticky green seeds from the cotton fiber.

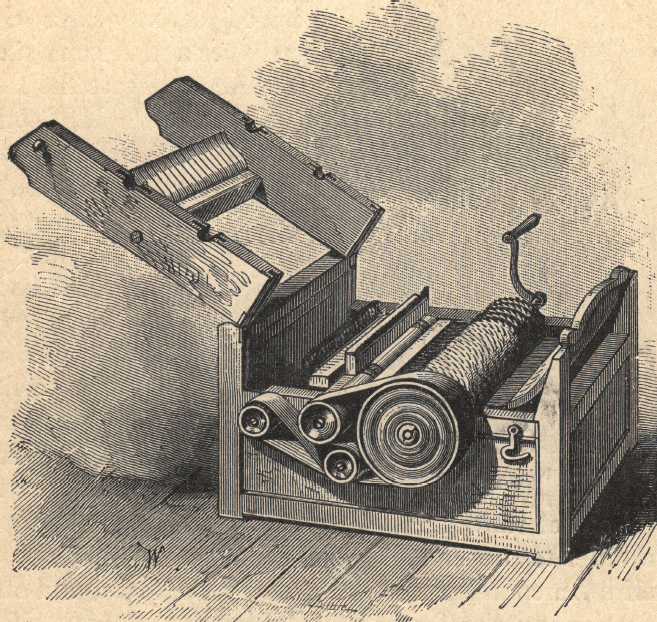

In 1793, in as little as ten days, Eli Whitney built a machine that could ease the labor of deseeding short-staple cotton. His cotton gin consisted of a wooden box with a mesh screen, rollers, brushes, and wire hooks. The cotton boll was drawn through the mesh, where wire hooks caught the seeds and the rotating brushes then swept the cotton lint into a tray. Whitney’s gin could clean as much cotton fiber in one hour as several workers could clean in a day. Recognizing the gin’s value, Whitney received a U.S. patent, but because the machine was easy to duplicate, he never profited from his invention.

Fortunately, Whitney had other ideas that proved more profitable. In June 1798, amid U.S. fears of a war with France, the U.S. government granted him an extraordinary contract to produce 4,000 rifles in eighteen months. Rifles were then produced individually by highly trained artisans, but the inventor claimed he could devise a machine to manufacture guns in large quantities. By January 1801, having produced only 500 rifles, Whitney met with national political leaders to reassure them that success was near. Adapting the plan of Honoré Blanc, a French mechanic who devised a musket with interchangeable parts, Whitney demonstrated the potential for using machines to produce various parts of a musket, which could then be assembled in mass quantities. With Jefferson’s enthusiastic support, the federal government extended Whitney’s contract, and by 1809 his New Haven factory was turning out 7,500 guns annually.

Whitney’s factory became a model for the American system of manufacturing, in which water-powered machinery and the division of production into many small tasks allowed less skilled workers to produce mass quantities of a particular item, like guns or shoes. Whitney viewed this system as a boon to men and women who were unable or unwilling to obtain apprenticeships in skilled crafts. In factories, they could be trained quickly to do a particular task and thereby support themselves or supplement family earnings from farming.

The factories developed by Whitney and Slater became training grounds for younger mechanics and inventors who devised improvements in machinery or set out to solve new technological puzzles. Their efforts also transformed the lives of generations of workers—enslaved and free—who planted and picked the cotton, spun the yarn, wove the cloth, and sewed the clothes that cotton gins and spinning mills made possible.