Education for a New Nation

The desire to create a specifically American culture began as soon as the Revolution ended. In 1783 Noah Webster, a schoolmaster, declared that “America must be as independent in literature as in Politics, as famous for arts as for arms.” To this end, the twenty-five-year-old Webster published the American Spelling Book, which by 1810 had become the second best-selling book in the United States (the Bible was the first). In 1828 Webster produced his American Dictionary of the English Language.

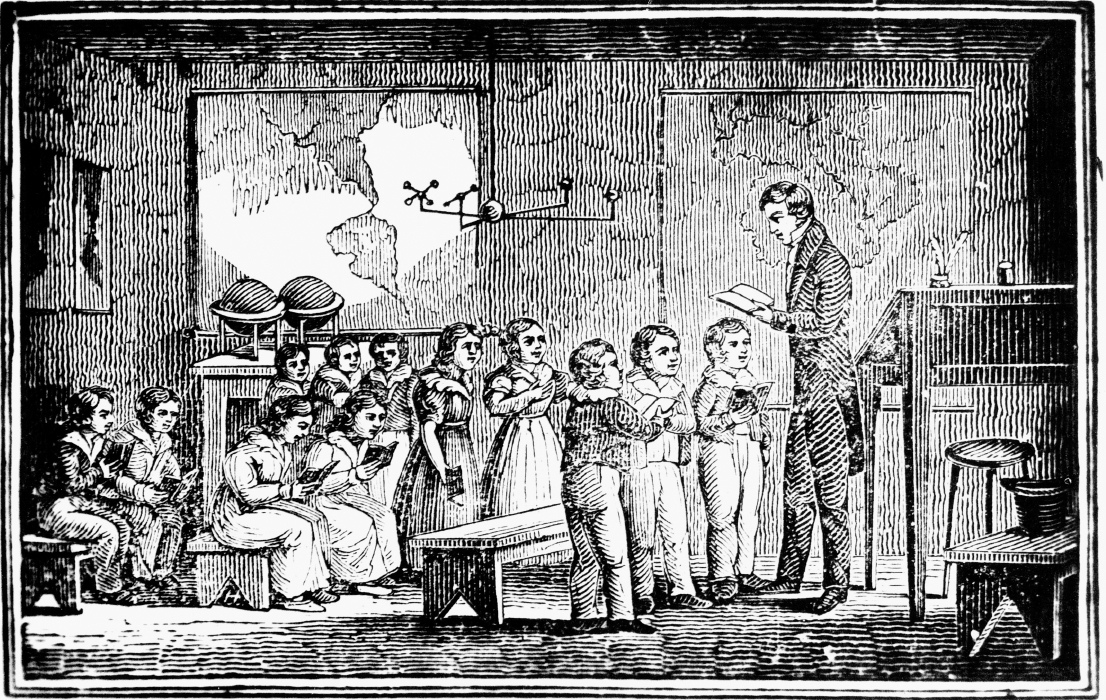

Webster’s books were widely used in the nation’s expanding network of schools and academies and led to more standardized spelling and pronunciation of commonly used words. Before the Revolution, public education for children, which focused on basic reading and writing skills, was widely available in New England and the Middle Atlantic region. In the South, only those who could afford private schooling—perhaps a quarter of the boys and 10 percent of the girls—received any formal instruction. Few young people enrolled in high school in any part of the colonies, and far fewer attended college. Following the Revolution, state and national leaders proposed ambitious plans for public education. In 1789 Massachusetts became the first state to institute free public elementary education for all children, and private academies and boarding schools proliferated throughout the nation.

Before 1790, the American colonies boasted nine colleges that provided further education for young men, including Harvard, Yale, King’s College (Columbia), Queen’s College (Rutgers), and the College of William and Mary. After independence, many Americans worried that these institutions were tainted by British and aristocratic influences. Situated in urban centers or crowded college towns, they were also criticized as centers of vice where youth might be corrupted by “scenes of dissipation and amusement.” New colleges based on republican ideals needed to be founded.

Frontier towns offered opportunities for colleges to enrich the community and benefit the nation. Located in isolated villages, these colleges assured parents that students would focus on education. The young nation benefited as well, albeit at the expense of Indians and their lands. The founders of Franklin College in Athens, Georgia, encouraged white settlement in the state’s interior, an area still largely populated by Creeks and Cherokees. And frontier colleges provided opportunities for ethnic and religious groups outside the Anglo-American mainstream—like Scots-Irish Presbyterians—to cement their place in American society.

Frontier colleges were organized as community institutions in which extended families—composed of administrators and faculty, their wives and children, servants and slaves, and students—played the central role. The familial character of these colleges—and their lower tuition fees—was also attractive to parents. Women were viewed as exemplars of virtue in the new nation, and the wives of professors were thus especially important in maintaining a refined atmosphere. They held salons where students could learn proper deportment and social skills. They also served as maternal figures for young adults living away from home. In some towns, students in local female academies joined college men on field trips and picnics to cultivate proper relations between the sexes.