The Beginnings of the Antislavery Movement

In the 1820s African Americans and a few white Quakers led the fight to abolish slavery. They published pamphlets, lectured to small audiences, and helped runaway slaves reach freedom. In 1829 David Walker wrote the most militant antislavery statement, Appeal . . . to the Colored Citizens of the World. The free son of an enslaved father, Walker left his North Carolina home for Boston in the 1820s and became a writer for Freedom’s Journal, the country’s first newspaper published by African Americans. In his Appeal, Walker warned that slaves would claim their freedom by force if whites did not agree to emancipate them. Some northern blacks feared Walker’s radical Appeal would unleash a white backlash, while Quaker abolitionists like Benjamin Lundy, editor of the Genius of Universal Emancipation, admired Walker’s courage but rejected his call for violence. Nonetheless the Appeal circulated widely among free and enslaved blacks, with copies spreading from northern cities to Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans, and Norfolk.

William Lloyd Garrison, a white Bostonian who worked on Lundy’s newspaper, was inspired by Walker’s radical stance. In 1831 he launched his own abolitionist newspaper, the Liberator. He urged white antislavery activists to embrace the goal of immediate emancipation without compensation to slave owners, a position first advocated by the English Quaker Elizabeth Heyrick.

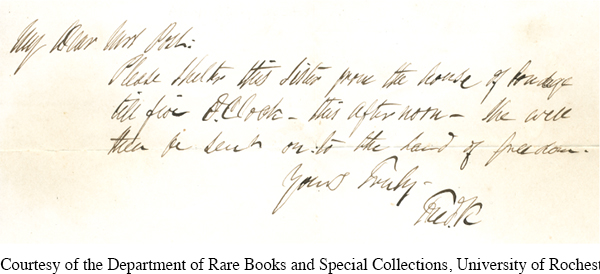

The Liberator demanded that whites take an absolute stand against slavery but use moral persuasion rather than armed force to halt its spread. With like-minded black and white activists in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City, Garrison organized the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) in 1833. By the end of the decade, the AASS boasted branches in dozens of towns and cities across the North. Members supported lecturers and petition drives, criticized churches that refused to denounce slavery, and proclaimed the U.S. Constitution a proslavery document. Some Garrisonians also participated in the work of the underground railroad, a secret network of activists who assisted fugitives fleeing enslavement.

In 1835 Sarah and Angelina Grimké joined the AASS and soon began lecturing for the organization. Daughters of a prominent South Carolina planter, they had moved to Philadelphia and converted to Quakerism. As white Southerners, their denunciations of slavery carried particular weight. Yet as women, their public presence aroused fierce opposition. In 1837 Congregationalist ministers in Massachusetts decried their presence in front of “promiscuous” audiences of men and women, but 1,500 female millworkers still turned out to hear them at Lowell’s city hall.

Maria Stewart, a free black widow in Boston, spoke out against slavery even earlier. In 1831 to 1832, she lectured to mixed-sex and interracial audiences, demanding that northern blacks take more responsibility for ending slavery and fighting racial discrimination. In 1833 free black and white Quaker women formed an interracial organization, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, which advocated the boycott of cotton, sugar, and other slave-produced goods.

The abolitionist movement quickly expanded to the frontier, where debates over slave and free territory were especially intense. In 1836 Ohio claimed more antislavery groups than any other state, and Ohio women initiated a petition drive to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. The petition campaign, which spread across the North, inspired the first national meeting of women abolitionists in 1837. Other antislavery organizations, like the AASS, recruited male and female abolitionists, black and white. And still others remained all-white, all-black, and single-sex.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 370

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 274

Chapter Timeline