The Election of 1860

Explore

See Document 12.4 for the Republican Party’s vision of America in 1860.

Brown’s hanging set the tone for the 1860 presidential campaign. The Republicans met in Chicago five months after Brown’s execution and distanced themselves from the more radical wing of the abolitionist movement. The party platform condemned both John Brown and southern “Border Ruffians,” who initiated the violence in Kansas. The platform accepted slavery where it already existed, but continued to advocate its exclusion from western territories. Finally, the platform insisted on the need for federally funded internal improvements and protective tariffs. The Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln as their candidate for president. Recognizing the impossibility of gaining significant votes in the South, the party focused instead on winning large majorities in the Northeast and Midwest.

The Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina. Although Stephen Douglas was the leading candidate, southern delegates were still angry with him over Kansas being admitted as a free state. When Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis introduced a resolution to protect slavery in the territories, Douglas’s northern supporters rejected it. President Buchanan also came out against Douglas, and the Democratic convention ended without choosing a candidate. Instead, various factions met separately. A group of largely northern Democrats met in Baltimore and nominated Douglas. Southern Democrats selected John Breckinridge, the vice president, a slaveholder, and an advocate of annexing Cuba. The Constitutional Union Party, comprised mainly of former southern Whigs, advocated “no political principle other than the Constitution of the country, the union of the states, and the enforcement of the laws.” Its members nominated Senator John Bell of Tennessee.

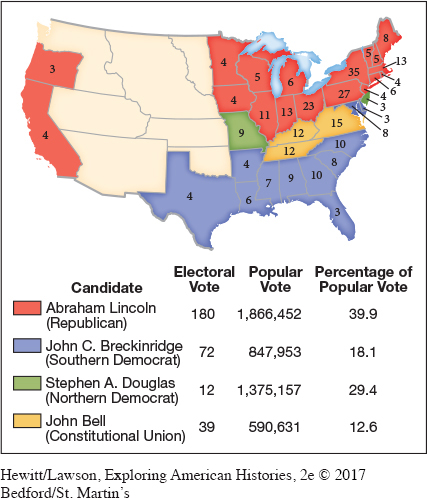

Although Lincoln won barely 40 percent of the popular vote, he carried a clear majority in the electoral college. With the admission of Minnesota and Oregon to the Union in 1858 and 1859, free states outnumbered slave states eighteen to fifteen, and Lincoln won all but one of them. Moreover, free states were more populous than slave states and therefore controlled a large number of electoral votes. Douglas ran second to Lincoln in the popular vote, but Bell and Breckinridge captured more electoral votes than Douglas did. Despite a deeply divided electorate, Lincoln became president (Map 12.3).

Although many abolitionists were wary of the Republicans, who were willing to leave slavery alone where it existed, most were nonetheless relieved at Lincoln’s victory and hoped he would become more sympathetic to their views once in office. Meanwhile, southern whites, especially those in the deep South, were furious that a Republican had won the White House without carrying a single southern state.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 403

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 299

Chapter Timeline