Introduction to Chapter 13

13

Civil War

1861–1865

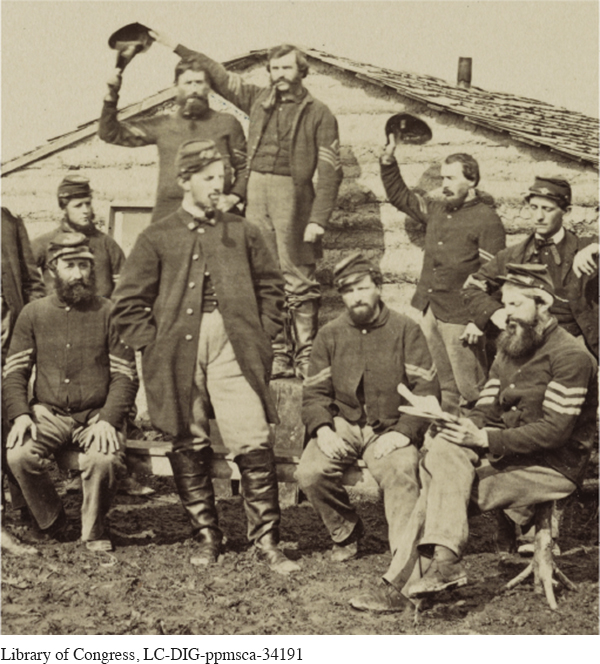

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Union Soldiers in Camp c. 1863

The Civil War was the first military conflict in U.S. history to be photographically documented. Many photographers took formal portraits of soldiers, individually or in groups, while others captured the bloody aftermath of battles. This picture offers a rare informal glimpse of soldiers in camp. Their range of poses and expressions suggests the various ways that soldiers responded to a lull in the conflict. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 13.2.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Explain why southern states seceded and describe the advantages and disadvantages that marked the Confederacy and the Union at the beginning of the Civil War.

Describe the changing roles of African Americans, free and enslaved, in the war and the growing sentiment for emancipation in the North.

Evaluate how the war changed northern and southern political priorities and the lives of soldiers and civilians.

Identify turning points in the Civil War, including key battles in the eastern and western theaters of war, and explain the factors that led to Union victory and the abolition of slavery.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Born into slavery in 1818, Frederick Douglass became a celebrated orator, editor, and abolitionist in the 1840s. In 1845 Douglass published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, which described his enslavement in Maryland, his defiance against his masters, and his eventual escape to New York in 1838 with the help of Anna Murray, a free black servant.

After marrying in New York, Frederick and Anna moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and changed their last name to Douglass to avoid capture. In 1841 the American Anti-Slavery Society hired Frederick to present his vivid tale of slave life in public. Four years later, Douglass launched a British lecture tour that attracted enthusiastic audiences. Supporters in Britain purchased his freedom, and Douglass returned to Massachusetts a free man in 1847.

Late that year, Frederick moved to Rochester, New York, with Anna and their children to launch his abolitionist paper, the North Star. Soon after, he broke with the Garrisonians and embraced the Liberty Party and eventually the Republicans. When war erupted in April 1861, Douglass lobbied President Lincoln relentlessly to make emancipation a war aim.

Initially Douglass feared that Lincoln was more committed to reconstituting the Union than abolishing slavery. But when the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Douglass spoke enthusiastically on its behalf. He also argued that it was essential for black men to serve in the Union army. When African Americans were finally allowed to join in 1862 to 1863, Douglass helped recruit volunteers but also protested discrimination against black troops and the denial of black civil rights.

Like Douglass, Rose O’Neal was born on a Maryland plantation, but she was white and free. Her father was John O’Neal, a planter who was killed in 1817 when Rose was about four. In her teens, she and her sister moved to Washington, D.C., where their aunt ran a fashionable boardinghouse. Her boarders included John C. Calhoun, whose states’ rights views Rose eagerly embraced. Rose was welcomed into elite social circles and in 1835 married Virginian Robert Greenhow, who worked for the State Department.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow quickly became a favorite Washington hostess, entertaining congressmen, cabinet ministers, and foreign diplomats. Ardent proslavery expansionists, the Greenhows supported efforts to acquire Cuba and expand slavery into western territories. When Robert died in 1854, Rose and their four children remained in D.C. and continued to entertain powerful political leaders.

In May 1861, as the Civil War commenced, a U.S. army captain about to join the Confederate cause recruited Greenhow to head an espionage ring in Washington, D.C. With her close ties to southern sympathizers in the capital, Greenhow gathered intelligence on Union plans. Although she initially avoided suspicion, by August 1861 Greenhow was investigated and placed under house arrest. After continuing to smuggle out letters, she was sent to the Old Capitol Prison in January 1862. When Greenhow again managed to transmit information, she was exiled to Richmond, where Confederate president Jefferson Davis hailed her as a hero.

The American histories of Frederick Douglass and Rose O’Neal Greenhow were shaped by the conflict over slavery, which culminated in secession and war. They were among hundreds of thousands of Americans who saw the war as a means to achieve their goals: a free nation, a haven for slavery, or a reunited country. Once conflict erupted at Fort Sumter in April 1861, more southern states seceded although four slave states, reluctantly, remained in the Union. Even with the addition of more states, the Confederacy lagged behind the Union in population, industrial and agricultural production, and railroad lines. These differences became more important as the war unfolded. Initially, however, skilled officers and knowledge of the southern terrain benefited the Confederate army. On the home front, hundreds of thousands of Americans labored on farms and in factories, burgeoning government offices, and hospitals to support the Union or the Confederacy. After 1862, tens of thousands of African Americans joined the Union army, both free blacks and enslaved men freed by Union forces. The next year, the Emancipation Proclamation ensured that a Union victory would eradicate slavery. As the war dragged on, antiwar protests erupted North and South, fueled by inflation, conscription acts, and mounting casualties. Finally in 1865, the greater resources of the North, complemented by General Ulysses S. Grant’s hard war strategy, led to Union victory and the final abolition of slavery.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 413

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 305

Chapter Timeline