Introduction to Chapter 14

14

Emancipation and Reconstruction

1863–1877

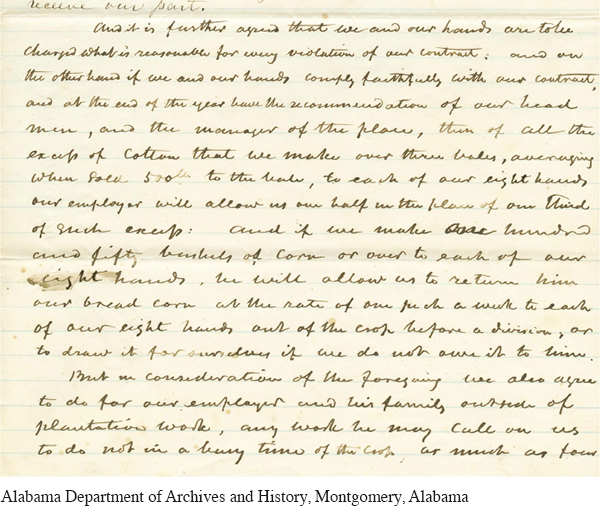

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Sharecropping Agreement, 1870

After the end of slavery, plantation owners needed to find new ways to work their land and former slaves needed to find employment. As a result, freedpeople sought to enter into sharecropping agreements, such as the one shown here, to farm on behalf of landowners because they lacked money and tools and wanted to farm their own land. However, despite their best efforts, they usually found themselves in debt to the white planter-merchants who controlled the accounts and sold them supplies. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 14.4.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Discuss the challenges newly freed African Americans faced and how they responded to them.

Analyze the influence of the president and Congress on Reconstruction policy and evaluate the successes and shortcomings of the policies they enacted.

Evaluate the changes that took place in the society and economy of the South during Reconstruction.

Explain how and why Reconstruction came to an end by the mid-1870s.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

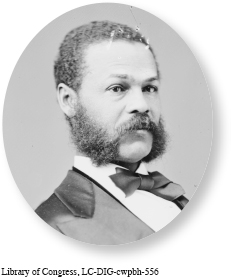

Jefferson Franklin Long spent his life improving himself and the lives of others of his race. Born a slave in Alabama in 1836, Long showed great resourcefulness in profiting from the limited opportunities available to him under slavery. His master, a tailor who moved his family to Georgia, taught him the trade, but Long taught himself to read and write. When the Civil War ended, he opened a tailor shop in Macon, Georgia. His business success allowed him to venture into Republican Party politics. Elected as Georgia’s first black congressman in 1870, Long fought for the political rights of freed slaves. In his first appearance on the House floor, he opposed a bill that would allow former Confederate officials to return to Congress, noting that many belonged to secret societies, such as the Ku Klux Klan, that intimidated black citizens. Despite his pleas, the measure passed, and Long decided not to run for reelection.

By the mid-1880s, Long had become disillusioned with the ability of black Georgians to achieve their objectives via electoral politics. Instead, he counseled African Americans to turn to institution building as the best hope for social and economic advancement. Long helped found the Union Brotherhood Lodge, a black mutual aid society with branches throughout central Georgia, which provided social and economic services for its members. He died in 1901, as political disfranchisement and racial segregation swept through Georgia and the rest of the South.

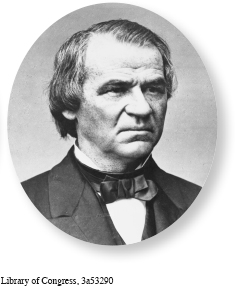

Jefferson Long and Andrew Johnson shared many characteristics, but their views on race could not have been more different. Whereas Long fought for the right of self-determination for African Americans, Johnson believed that whites alone should govern. Born in 1808 in Raleigh, North Carolina, Johnson grew up in poverty. At the age of thirteen or fourteen, he became a tailor’s apprentice and, after moving to Tennessee in 1826, like Long, opened a tailor shop. The following year, Johnson married and began to prosper, purchasing a farm and a small number of slaves.

As he made his mark in Greenville, Tennessee, Johnson became active in Democratic Party politics. A social and political outsider, Johnson gained support by championing the rights of workers and small farmers against the power of the southern aristocracy. Political success followed, and by the time the Civil War broke out, he was a U.S. senator.

When the Civil War erupted, Johnson remained loyal to the Union even after Tennessee seceded in 1861. President Abraham Lincoln rewarded Johnson by appointing him as military governor of Tennessee. In 1864 the Republican Lincoln chose the Democrat Johnson to run with him as vice president. Less than six weeks after their inauguration in March 1865, Johnson became president upon Lincoln’s assassination.

Fate placed Reconstruction in the hands of Andrew Johnson. After four years, the brutal Civil War had come to a close. Yet the hard work of reunion remained. Toward this end, President Johnson oversaw the reestablishment of state governments in the former Confederate states. He considered the southern states as having fulfilled their obligations for rejoining the Union, even as they passed measures that restricted black civil and political rights. Most Northerners reached a different conclusion. Having won the bloody war, they feared losing the peace to Johnson and the defeated South.

The American histories of Andrew Johnson and Jefferson Long intersected in Reconstruction, amid hard-fought battles to determine the fate of the postwar South and the meaning of freedom for newly emancipated African Americans. Former slaves sought to reunite their families, obtain land, and seek an education. President Johnson rejected their pleas for assistance to fulfill these aims. However, Congress passed laws to ensure civil rights and extend the vote to African American men, although African American women, like white women, remained disenfranchised. In the South, whites attempted to restore their economic and political power over African Americans by resorting to intimidation and violence. By 1877, they succeeded in bringing Reconstruction to an end with the consent of the federal government.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 447

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 330

Chapter Timeline