Introduction to Chapter 15

15

The West

1865–1896

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Buffalo Hunting, c. 1875

This image of a buffalo (bison) hunt was rendered on a buffalo hide. Buffalo were an important resource for Native Americans on the Great Plains, and the decline of this resource at the hands of white settlers not only changed the landscape of the West but also irreparably changed the lives of the Indians who lived there. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 15.1.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Explain the motives and incentives that led to settling of the trans-Mississippi West and the technological developments that encouraged it.

Explain the strategies used by the U.S. government to control the lives of Native Americans in the West and Indians’ reactions to these efforts.

Describe the role of the mining and lumber industries in the economic and social development of the West.

Identify factors that led to the rise of commercial ranching and contrast the image of life in the West for ranchers and farmers with the reality.

Explain the cultural diversity of the far West and the ethnic tensions that followed from this diversity.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Born in 1860, Phoebe Ann Moses grew up east of the Mississippi, seventy miles north of Cincinnati, Ohio. One of seven surviving children, she was sent to an orphanage at the age of nine, after her father died and her mother could not care for all her children. After working for a farm family, she ran away at the age of twelve and found a new home with a recently remarried widow. There, Phoebe Ann learned to ride and hunt and became an expert shot with a rifle. At fifteen, she entered a shooting contest and defeated a professional marksman, Frank Butler. The two married in 1876. Phoebe Ann changed her professional name to “Annie Oakley,” and she and Butler toured the Midwest in an act that featured precision shooting.

In 1884 Oakley and Butler met William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in New Orleans. In 1883, as the western frontier began to recede and the U.S. government relocated Native Americans who lived there, Cody attempted to recapture and reinvent the frontier experience by staging “Wild West” shows. A year later, he hired Oakley, with Butler serving as her manager. For the next fifteen years, Oakley was the star of the show. Wearing a fringed skirt, an embroidered blouse, and a broad felt hat, she stood atop her horse and performed amazing feats of marksmanship. Oakley toured Europe and fascinated heads of state and audiences alike with her version of “western authenticity.” Fans at home and overseas displayed great nostalgia for a fast-diminishing era. When the census of 1890 reported that no open land was left to settle and thus no western frontier was left to conquer, Oakley’s popularity soared. She continued performing in Wild West shows until her death in 1926.

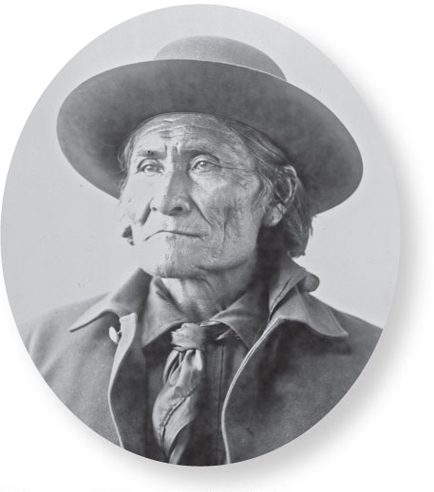

While Annie Oakley portrayed the Wild West, Geronimo had lived it. Born to a Chiricahua Apache family in what was then northern Mexico (present-day Arizona and New Mexico), Geronimo led Apaches in a constant struggle against Spain, Mexico, and the United States. In 1851 a band of Mexicans raided an Apache camp, murdering Geronimo’s mother, wife, and three children. After fighting Mexicans, Geronimo clashed with U.S. troops and evaded capture until 1877, when an Indian agent arrested him in New Mexico. Sent to a reservation, Geronimo escaped and for eight years engaged in daring raids against his foes. In 1886 two Chiricahua scouts led the U.S. military to Geronimo. Against an army of five thousand soldiers, the Apache warrior, with a band of eighteen fighters and some women and children, finally surrendered and was eventually relocated by the U.S. government to Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

The once-elusive warrior decided to take advantage of his legendary reputation and America’s growing fascination with the mythic West. He sold photos of himself and pieces of his clothing; he appeared at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, selling bows and arrows and autographs; and in 1905 he rode in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade as an example of a “tamed” Indian. Despite all of this, Geronimo never gave up the idea of returning to his birthplace. As long as the U.S. government prohibited him from going back to his ancestral lands in the Southwest, he considered himself a “prisoner of war.” And so he remained until his death in 1909.

The American histories of Annie Oakley and Geronimo were profoundly different, yet they both contributed to the creation of a shared story, the myth of the American West. The West has great fascination in American culture. Stories about the frontier have romanticized both cowboys and Indians. These stories have also glorified individualism, self-help, and American ingenuity and minimized cooperation, organization, and the role of foreign influence in developing the West. As the American histories of Annie Oakley and Geronimo make clear, reality presents a more complicated picture of a diverse region initially inhabited by native peoples who were pushed aside by the arrival of white settlers and immigrants. In the areas known as the Great Plains and the far West, women took on new roles, and new cities emerged to accommodate the influx of miners, ranchers, and farmers.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 481

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 354

Chapter Timeline