Introduction to Chapter 18

18

Cities, Immigrants, and the Nation

1880–1914

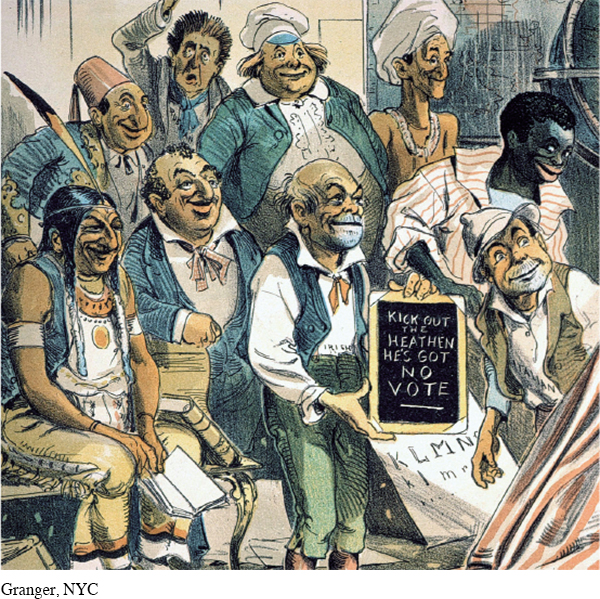

WINDOW TO THE PAST

“Be Just—Even to John Chinaman, 1893”

This image, from a cartoon supporting the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), appeared in the satirical magazine Judge. The Chinese were singled out for harsh treatment because they competed with white workers for jobs in the West. Of all the immigrants entering the country after the Civil War, the Chinese were most often viewed as incapable of being assimilated. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 18.7.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Explain how the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century immigrants differed from those who came before them and how they were received by native-born Americans.

Explain why farmers, small-town residents, and African Americans from the South migrated to cities, and identify the challenges and technological changes they encountered.

Evaluate the benefits and liabilities of urban political machines and identify who supported and opposed them.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

In the fall of 1905, Beryl Lassin faced a difficult choice. Living in a shtetl (a Jewish town) in western Russia, Lassin had few if any opportunities as a young blacksmith. Beryl and his wife, Lena, lived at a dangerous time in Russia. Jews were subject to periodic pogroms, state-sanctioned outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence carried out by local Christians. Beryl also faced a discriminatory military draft that required conscripted Jews to serve twenty-year terms in the army, far longer than Christians. Beryl decided he should quickly follow his wife’s brother to the United States. With the understanding that his wife would follow as soon as possible, Beryl set sail for America on October 7, 1905. He was crammed into the steerage belowdecks with hundreds of other passengers. Ten days later he disembarked in New York harbor at Ellis Island, the processing center for immigrants, where he stood in long lines and underwent a strenuous medical examination to ensure that he was fit to enter the country. Once he proved he had someplace to go, Beryl boarded a ferry across the Hudson that took him to a new life in the United States.

Less than a year later, Lena joined her husband. Over the next decade, the couple had five children. Shortly after the youngest girl was born, Lena died and Beryl, now called Ben, was forced to place his children in a group home and foster care. The children were reunited with their father when Ben remarried, but life was still difficult. To make ends meet, his three eldest boys left school and went to work. Still, Ben’s family managed to leave the crowded Lower East Side for Harlem and then the Bronx. Ben preferred to speak in Yiddish and never learned to read English. Nor did he become an American citizen. His children, however, were all citizens because they had been born in the United States.

On June 8, 1912, another immigrant followed a similar route but ended up taking a different journey. Seventeen years old and unmarried, Maria Vik decided to leave her home in rural Hungary. As a Catholic, Maria did not experience the religious persecution that Beryl did. Like many other Hungarians, Maria left to help support her family back in the old country. She had an aunt living in the United States, and she came across with a Hungarian couple who escorted young women for domestic service in America.

Maria, too, landed at Ellis Island and passed the rigorous entry exams. Soon she boarded a train for Rochester in western New York. There she worked as a cook for a German physician, learned English, and led an active social life within the local Hungarian community. She married Karoly (Charles) Takacs, a cabinetmaker from Hungary, who had come to avoid the military draft. Charles became a U.S. citizen in May 1916. By marrying him, Mary, as she was now called, became a citizen as well.

The couple purchased a farm in Middleport, New York. Because so many Hungarians lived in the area, Mary began to speak more English only when the oldest of her four children entered kindergarten.

The American histories of Beryl and Maria took one to the urban bustle of New York City, the other to a quiet rural village in western New York State. However, as different as their lives in America were, neither regretted their choice to immigrate. Like millions of others, they had come to America to build better lives for themselves and their families, and both saw their children and grandchildren succeed in ways that they could have only dreamed of in their native countries. Indeed, two grandchildren of Beryl and Maria, Steven Lawson and Nancy Hewitt, respectively—became historians, got married, and wrote this textbook. The experiences of these families, like countless others, reflect the complicated ways that immigrants’ lives were transformed at the same time the nation itself was being transformed.

The Lassins and the Viks were part of a flood of immigrants who entered the United States from 1880 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Unlike the majority of earlier immigrants, who had come from northern Europe, most of the more than 20 million people who arrived during this period came from southern and eastern Europe. A smaller number of immigrants came from Asia and Mexico. Most remained in cities, which grew as a result. Urban immigrants were welcomed by political bosses, who saw in them a chance to gain the allegiance of millions of new voters. At the same time, their coming upset many middle- and upper-class city dwellers who blamed these new arrivals for lowering the quality of urban life.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 583

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 430

Chapter Timeline