Introduction to Chapter 20

20

Empire and Wars

1898–1918

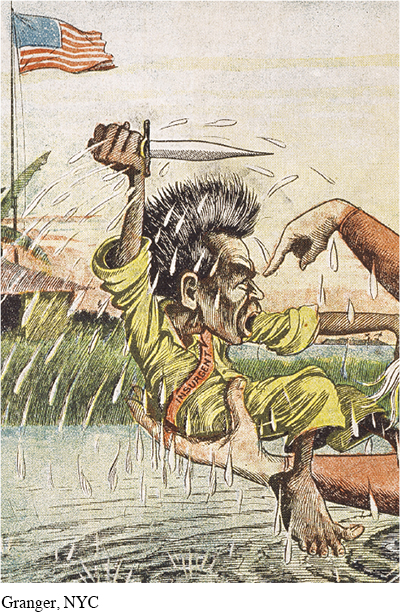

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Detail from Cartoon “A Bigger Job than He Thought For,” 1899

This image portrays a cartoon from a newspaper in 1899 opposing the war in the Philippines. The annexation of the islands after the War of 1898 led to a rebellion against U.S. military occupation by the Filipinos, a bloody insurrection that lasted for three years. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 20.3.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the reasons behind U.S. imperialism in the 1890s and early twentieth century.

Compare the interventions in Cuba and the Philippines and their effects on U.S. attitudes toward nation building.

Compare Roosevelt’s “big stick” diplomacy, Taft’s dollar diplomacy, and Wilson’s moral diplomacy and identify their benefits and drawbacks.

Summarize the reasons for U.S. intervention in World War I and evaluate their relative importance.

Describe the domestic effects of World War I on U.S. economics, culture, and politics.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

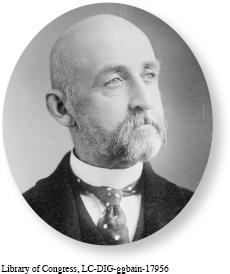

Alfred Thayer Mahan came from a military family. Born in 1840, he grew up in West Point, New York, where his father served as dean of the faculty at the U.S. Military Academy. Seeking to emerge from his father’s shadow, Alfred attended the U.S. Naval Academy, receiving his commission in 1861, just as the Civil War was getting under way. His wartime experience convinced him that the navy needed a dramatic overhaul.

After the war, Captain Mahan built his reputation as a military historian and strategist at the U.S. Naval War College. In 1890 he published The Influence of Sea Power upon History, in which he argued that great imperial powers in modern history had succeeded because they possessed strong navies and merchant marines. In his view, sea power had allowed these nations to defeat their enemies, conquer territories, and establish colonies. Appearing at a time when European nations were embarking on a new round of empire building, this book had an enormous influence on U.S. imperialists, including Theodore Roosevelt. Mahan’s work reinforced the belief of men like Roosevelt that the long-term prospects of the United States depended on the acquisition of strategic outposts in Asia and the Caribbean that could guarantee U.S. access to overseas markets.

As the economic and strategic importance of the Caribbean grew in the minds of imperial strategists such as Mahan and Roosevelt, the Cuban freedom fighter José Martí developed a very different vision of the region’s future. Born in 1853, Martí got involved in the fight for Cuban independence from Spain as a teenager. In 1869, at age seventeen, he was arrested for protest activities during a revolutionary uprising against Spain. Sentenced to six years of hard labor, Martí was released after six months and was forced into exile. He returned to Cuba in 1878, only to be arrested and deported again the following year.

Martí settled in the United States, where, along with other Cuban exiles, he continued to promote Cuban independence and the establishment of a democratic republic. He conceived of the idea of Cuba Libre (Free Cuba) not just as a struggle for political independence but also as a social revolution that would erase unfair distinctions based on race and class. Martí united disparate elements in expatriate communities in the United States and the Caribbean under the banner of a single Cuban Revolutionary Party.

When Cubans once again rebelled against Spain in 1895, Martí returned to Cuba to fight alongside his comrades. On May 19, only three months after he had returned to Cuba, Martí died in battle. Cuba ultimately won its independence from Spain, but Martí’s vision of Cuba Libre was only partially realized. In 1898 the United States intervened on the side of the Cuban rebels, guaranteeing their victory but not their freedom.

The American histories of Alfred Thayer Mahan and José Martí embodied disparate understandings of the United States’ relationship with the rest of the world. Up until the late nineteenth century, most Americans associated colonialism with the European powers and saw overseas expansion as incompatible with U.S. values. In this context, they shared Martí’s point of view. The imperialism espoused by Mahan and others therefore represented a reversal of traditional U.S. attitudes. Supporters of U.S. imperialism saw the acquisition and control of overseas territories, by force if necessary, as essential to the protection of U.S. interests. This perspective would come to dominate U.S. foreign policy in the early twentieth century. Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, progressive presidents who sanctioned intervention in economic and moral issues at home, supported vigorous intervention in world affairs. Many progressives lined up with the imperialists because they supported foreign expansion as part of the inevitable progress of the nation. Just as they used government power to institute economic, political, and social reforms at home, so too did many progressives advocate U.S. intervention to reshape world affairs. Although Roosevelt and Wilson differed in style and approach, in foreign affairs they asserted America’s right to use its power to secure order and thwart revolution wherever U.S. interests were seen to be threatened. Having become a major power on the world stage in the early twentieth century, the United States chose to enter World War I, in which rival European alliances battled for imperial domination. The end of the war heightened America’s critical role in world affairs but brought neither lasting peace nor the dissolution of empire.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 649

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 479

Chapter Timeline