The Rise of the Southern Civil Rights Movement

With the war against Nazi racism over, African Americans expected to win first-class citizenship in the United States. During World War II, blacks waged successful campaigns to pressure the federal government to tackle discrimination and organizations such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the NAACP attacked racial injustice (see “The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement” in chapter 23). African American veterans returned home to the South determined to build on these victories, especially by extending the right to vote. Yet African Americans found that most whites resisted demands for racial equality.

In 1946 violence surfaced as the most visible evidence of many white people’s determination to preserve the traditional racial order. A race riot erupted in Columbia, Tennessee, in which blacks were killed and black businesses were torched. In South Carolina, Isaac Woodard, a black veteran still in uniform and on his way home on a bus, got into an argument with the white bus driver. When the local sheriff arrived, he pounded Woodard’s face with a club, permanently blinding the ex-GI. In Mississippi, Senator Theodore Bilbo, running for reelection in the Democratic primary, told white audiences that they could keep blacks from voting “by seeing them the night before” the election. Groups such as the NAACP and the National Association of Colored Women demanded that the president take action to combat this reign of terror.

In December 1946, President Truman responded by issuing an executive order creating the President’s Committee on Civil Rights. While the committee conducted its investigation, in April 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first black baseball player to enter the major leagues. This accomplishment proved to be a sign of changes to come.

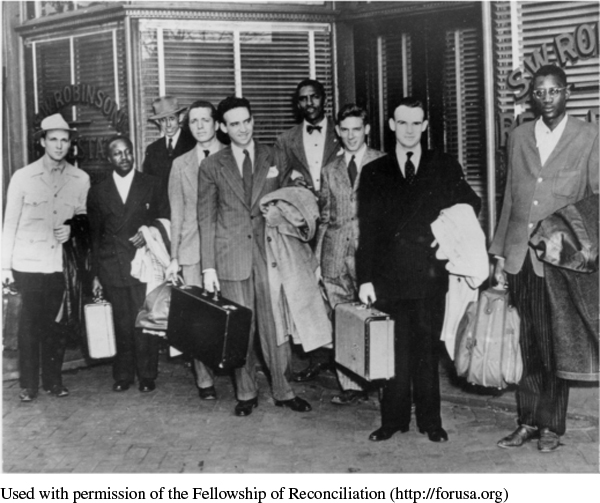

After extensive deliberations, the committee, which consisted of blacks and whites, northerners and southerners, issued its report, To Secure These Rights, on October 29, 1947. Placing the problem of “civil rights shortcomings” within the context of the Cold War, the report argued that racial inequality and unrest could only aid the Soviets in their global anti-American propaganda efforts. “The United States is not so strong,” the committee asserted, “the final triumph of the democratic ideal not so inevitable that we can ignore what the world thinks of us or our record.” A far-reaching document, the report called for racial desegregation in the military, interstate transportation, and education, as well as extension of the right to vote. The following year, under pressure from African American activists, the president signed an executive order to desegregate the armed forces.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 840

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 619

Chapter Timeline