Introduction to Chapter 5

5

War and Empire

1750–1774

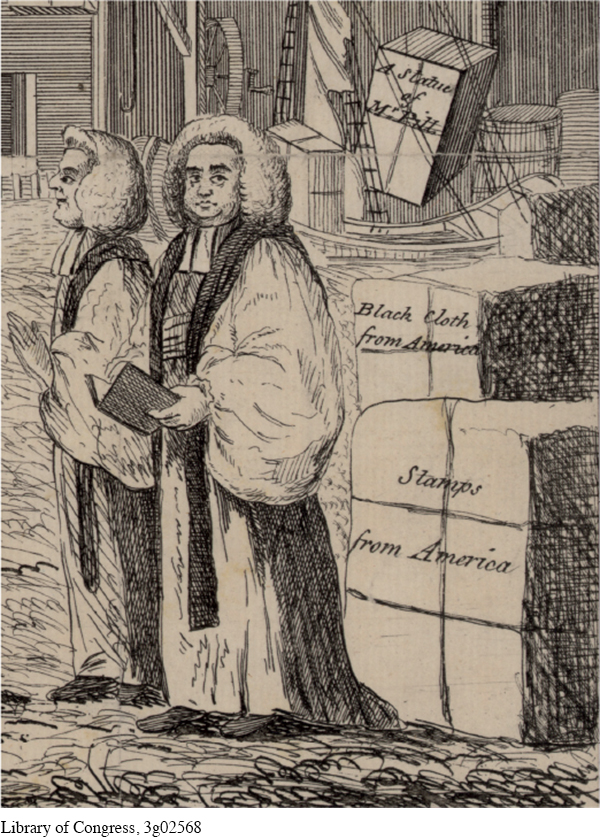

WINDOW TO THE PAST

The Stamp Act Repealed, 1766

In 1765 the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which imposed a tax on a variety of paper items and documents in the American colonies to help pay debts from the French and Indian War. But the Stamp Act aroused widespread protests in the colonies, forcing its repeal in 1766. This political cartoon depicts a funeral service for the American stamps held by its British supporters. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 5.3.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the causes and consequences of the French and Indian War.

Explain how British policies following the French and Indian War fostered colonial grievances.

Analyze the major British policies from 1764 to 1774 and how colonial responses to them became more unified.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

Praised as the father of the United States, George Washington remained a loyal British subject for forty-three years. He was born in 1732 to a prosperous farm family in eastern Virginia. When his father died in 1743, George became the ward of his half-brother Lawrence, who took control of the family’s Mount Vernon estate. Lawrence’s father-in-law, William Fairfax, was an agent for Lord Fairfax, one of the chief proprietors of the colony. When George was sixteen, William hired him to help survey Lord Fairfax’s land on Virginia’s western frontier.

As a surveyor, George journeyed west, coming into contact with Indians, both friendly and hostile, as well as other colonists seeking land. George began investing in western properties, but when Lawrence Washington died in 1752, George suddenly became head of a large estate. He gradually expanded Mount Vernon’s boundaries and its enslaved workforce, increasing its profitability.

George was soon appointed Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia militia, and in the fall of 1753 Virginia’s governor sent him to warn the French against encroaching on British territory in the Ohio River valley. The French commander rebuffed Washington and, within six months, gained control of a British post near present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and named it Fort Duquesne. With help from Indians hostile to the French, Washington’s surprise attack on Fort Duquesne in May 1754 led the governors of Virginia and North Carolina to provide the newly promoted Colonel Washington with more troops. The French then responded with a much larger force that compelled Washington to surrender.

Washington’s fortunes and his family increased when he married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759. With more land to defend, Washington supported efforts to extend Britain’s North American empire westward to create a protective buffer against European and Indian foes.

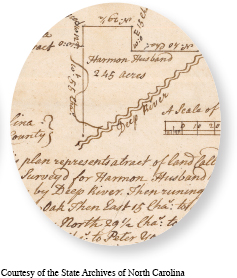

Like Washington, Hermon Husband hoped to improve his lot through hard work and new opportunities on the frontier. Born to a modest farm family in Maryland in 1724, he was swept up by George Whitefield’s preaching in 1739, but eventually joined the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Although his farm in Maryland was thriving, Husband explored prospects on the North Carolina frontier. In 1764 he settled with his family at Sandy Creek.

Husband once again proved a successful farmer, but he denounced wealthy landowners and speculators who made it difficult for small farmers to obtain sufficient land. He also challenged established leaders in the Quaker meeting and was among a number of worshippers disowned from the Cane Creek Friends Meeting in 1764. Disputes within radical Protestant congregations were not unusual in this period as members with deep religious convictions chose the liberty of their individual conscience over church authority.

In 1766 local farmers joined Husband in organizing the Sandy Creek Association, through which they sought to increase their political clout in order to combat corruption among local officials. The association disbanded after two years, but its ideas lived on in a group called the Regulation, which brought together frontier farmers to “regulate” government abuse. The Regulators petitioned the North Carolina Assembly and Royal Governor William Tryon, demanding legislative reforms and suing local officials for extorting labor, land, and money from poorer residents.

Husband quickly emerged as one of the organization’s chief pamphleteers, articulating the demands of the Regulators and echoing other colonial protesters of the period. Governor Tryon viewed the Regulators as threatening the colony’s peace and order and, in 1768 and 1771, had Husband and other Regulators arrested. This confirmed the group’s belief that they could not receive fair treatment at the hands of colonial officials. They then turned to extralegal methods to assert their rights, such as taking over courthouses so that legal proceedings against debt-ridden farmers could not proceed.

The American histories of Washington and Husband were shaped by both opportunities and conflicts. Mid-eighteenth-century colonial America offered greater opportunities for social advancement and personal expression than anywhere in Europe, but collective efforts to take advantage of these opportunities often led to tension and discord. Frontier conflicts foreshadowed a broader struggle for land and power within the American colonies. Religious and economic as well as political discord intensified in the mid-eighteenth century as upheavals among colonists increasingly occurred alongside challenges to British authority. Whatever their grievances, most colonists worked hard to reform systems they considered unfair or abusive before resorting to more radical means of instituting change.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 137

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 104

Chapter Timeline