Introduction to Chapter 8

8

The Early Republic

1790–1820

WINDOW TO THE PAST

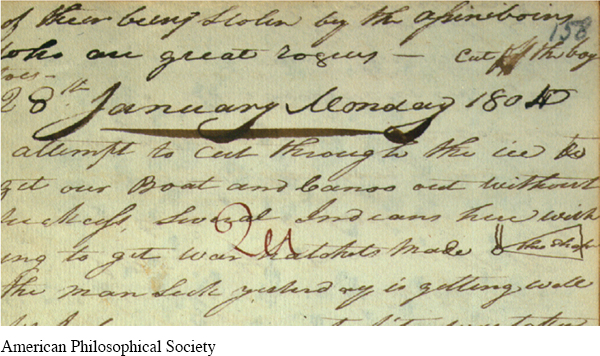

William Clark, Journal, January 28, 1805

William Clark kept a detailed journal of the 1804–1806 expedition he and Meriwether Lewis led to explore the American West. They were aided by many different Indian groups, especially the Mandan Indians along the Missouri River. They camped near the Mandan in the winter of 1804, before heading into the Rocky Mountains. Here Clark draws a Mandan war hatchet, which was crucial to the tribe’s defense. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 8.8.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Analyze the ways that social and cultural leaders worked to craft an American identity and how that was complicated by racial, ethnic, and class differences.

Interpret how the Democratic-Republican ideal of limiting federal power was transformed by international events, westward expansion, and Supreme Court rulings between 1800 and 1808.

Explain the ways that technology reshaped the American economy and the lives of distinct groups of Americans.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

When Parker Cleaveland graduated from Harvard University in 1799, his parents expected him to pursue a career in medicine, law, or the ministry. Instead, he turned to teaching. In 1805 Cleaveland secured a position in Brunswick, Maine, as professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Bowdoin College. A year later, he married Martha Bush. Over the next twenty years, the Cleavelands raised eight children on the Maine frontier, entertained visiting scholars, corresponded with families at other colleges, and boarded dozens of students. While Parker taught those students math and science, Martha trained them in manners and morals. The Cleavelands also served as a model of new ideals of companionate marriage, in which husbands and wives shared interests and affection.

Professor Cleaveland believed in using scientific research to benefit society. When Brunswick workers asked him to identify local rocks, Parker began studying geology and chemistry. In 1816 he published his Elementary Treatise on Mineralogy and Geology, providing a basic text for students and interested adults. He also lectured throughout New England, displaying mineral samples and performing chemical experiments.

The Cleavelands viewed the Bowdoin College community as a laboratory in which distinctly American values and ideas could be developed and sustained. So, too, did the residents of other college towns. Although less than 1 percent of men in the United States attended universities at the time, frontier colleges were considered important vehicles for bringing virtue—especially the desire to act for the public good—to the far reaches of the early republic. Yet several of these colleges were constructed with the aid of slave labor, and all were built on land bought or confiscated from Indians.

The purchase of the Louisiana Territory by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803 marked a new American frontier and ensured further encroachments on native lands. The territory covered 828,000 square miles and stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from New Orleans to present-day Montana. The area was home to tens of thousands of Indian inhabitants.

In the late 1780s, a daughter, later named Sacagawea, was born to a family of Shoshone Indians who lived in an area that became part of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1800 she was taken captive by a Hidatsa raiding party. Sacagawea and her fellow captives were marched hundreds of miles to a Hidatsa-Mandan village on the Missouri River. Eventually Sacagawea was sold to a French trader, Toussaint Charbonneau, along with another young Shoshone woman, and both became his wives.

In November 1804, an expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set up winter camp near the Hidatsa village where Sacagawea lived. The U.S. government sent Lewis and Clark to document flora and fauna in the Louisiana Territory, enhance trade, and explore routes to the Northwest. Charbonneau, who spoke French and Hidatsa, and Sacagawea, who spoke several Indian languages, joined the expedition as interpreters in April 1805.

The only woman in the party, Sacagawea traveled with her infant son strapped to her back. Although no portraits of her exist, her presence was crucial, as Clark noted in his journal: “The Wife of Chabono our interpreter we find reconsiles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions.” Sacagawea did help persuade Indian leaders to assist the expedition, but her extensive knowledge of the terrain and fluency in Indian languages were equally important.

The American histories of both Parker Cleaveland and Sacagawea aided the development of the United States. Cleaveland gained fame as part of a generation of intellectuals who symbolized Americans’ ingenuity. Although Sacagawea was not considered learned, her understanding of Indian languages and western geography was crucial to Lewis and Clark’s success. Like many other Americans, Sacagawea and Cleaveland forged new identities as the young nation developed. Still, racial, class, and gender differences made it impossible to create a single American identity. At the same time, Democratic-Republican leaders sought to shape a new national identity by promising to limit federal power and enhance state authority and individual rights. Instead, western expansion, international crises, and Supreme Court decisions ensured the expansion of federal power.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 241

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 179

Chapter Timeline