The Presidential Election of 1828

The election of 1828 tested the power of the two major factions in the Democratic-Republican Party. President Adams followed the traditional approach of “standing” for office. He told supporters, “If my country wants my services, she must ask for them.” Jackson and his supporters chose instead to “run” for office. They took their case directly to the voters, introducing innovative techniques to create enthusiasm among the electorate.

Van Buren managed the first truly national political campaign in U.S. history, seeking to re-create the original Democratic-Republican coalition among farmers, northern artisans, and southern planters while adding a sizable constituency of frontier voters. He was aided in the effort by Calhoun, who again ran for vice president and supported the Tennessee war hero despite their disagreement over tariffs. Jackson’s supporters organized state nominating conventions rather than relying on the congressional caucus. They established local Jackson committees in critical states like Virginia and New York. They organized newspaper campaigns and developed a logo, the hickory leaf, based on the candidate’s nickname, “Old Hickory.”

Jackson traveled the country to build loyalty to himself as well as to his party. His Tennessee background, rise to great wealth, and reputation as an Indian fighter ensured his popularity among southern and western voters. He also reassured southerners that he advocated “judicious” duties on imports, suggesting that he might try to lower the 1828 rates. At the same time, his support of the tariff of 1828 and his military credentials created enthusiasm among northern workingmen and frontier farmers.

President Adams’s supporters demeaned the “dissolute” and “rowdy” men who attended Jackson rallies. They also launched personal attacks on the candidate and on his wife, Rachel. They questioned the timing of her divorce from her first husband and remarriage to Jackson. A Cincinnati newspaper headline asked: “Ought a convicted adulteress and her paramour husband be placed in the highest offices of this free and Christian land?” See Document Project 9: The Election of 1828.

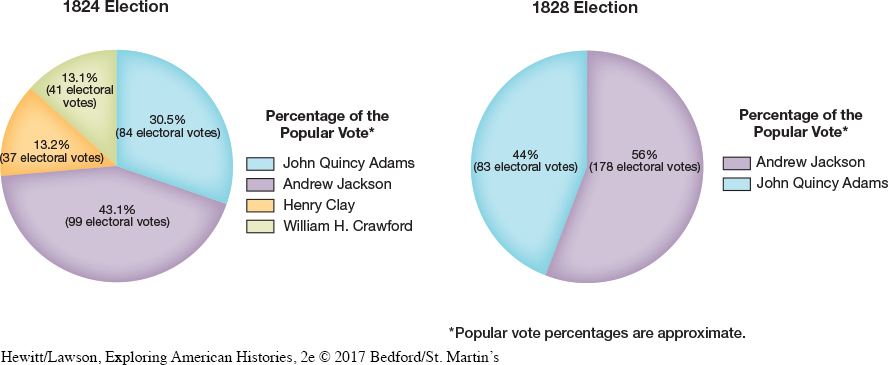

Adams distanced himself from his own campaign. He sought to demonstrate his statesmanlike gentility by letting others speak for him. This strategy worked well when only men of wealth and property could vote. But with an enlarged electorate and an astonishing turnout of more than 50 percent of eligible voters, Adams’s approach failed and Jackson became president (Figure 9.1).

The election of 1828 formalized a new party alignment. During the campaign Jackson and his supporters referred to themselves as “the Democracy” and forged a new national Democratic Party. In response Adams’s supporters called themselves National Republicans. The competition between Democrats and National Republicans heightened interest in national politics among ordinary voters and ensured that the innovative techniques introduced by Jackson would be widely adopted in future campaigns.

REVIEW & RELATE

How and why did the composition of the electorate change in the 1820s?

How did Jackson’s 1828 campaign represent a significant departure from earlier patterns in American politics?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 297

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 222

Chapter Timeline