16.1 EARLY THEORIES OF INHERITANCE

Thousands of years before Mendel, many societies carried out practical plant and animal breeding. The ancient practices were based on experience rather than on a full understanding of the rules of genetic transmission, but they were nevertheless highly successful. In Mesoamerica, for example, Native Americans chose corn (maize) plants for cultivation that had the biggest ears and softest kernels. Over many generations of such selection, their cultivated corn came to have less and less physical resemblance to its wild ancestral species. Similarly, people in the Eurasian steppes selected their horses for a docile temperament suitable for riding or for hitching to carts or sleds. Practical breeding of this kind provided the crops and livestock from which most of our modern domesticated animals and plants derive.

16.1.1 Early theories of heredity predicted the transmission of acquired characteristics.

The first written speculations about mechanisms of heredity were made by the ancient Greeks. Hippocrates (460–377 BCE), considered the founder of Western medicine, proposed that each part of the body in a sexually mature adult produces a substance that collects in the reproductive organs and that determines the inherited characteristics of the offspring. An implication of this theory is that any trait, or characteristic, of an individual can be transmitted from parent to offspring. Even traits that are acquired during the lifetime of an individual, such as muscle strength or bodily injury, were thought to be heritable because of the substance supposedly passed from each body part to the reproductive organs.

16-2

The theory that acquired characteristics can be inherited was invoked to explain such traits as the webbed feet of ducks, which were thought to result from many successive generations in which adult ducks stretched the skin between their toes while swimming and passed this trait to offspring. A few decades later, however, Aristotle (384–322 BCE) emphasized several observations that the theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics cannot account for:

- Traits such as hair color can be inherited, but it is difficult to see how hair—a nonliving tissue—could send substances to the reproductive organs.

- Traits that are not yet present in an individual can be transmitted to the offspring. For example, a father and his adult son can both be bald, even though the son was born before the father became bald.

- Parts of the body that are lost as a result of surgery or accident are not missing in the offspring.

From these and other observations, Aristotle concluded that the process of heredity transmits only the potential for producing traits present in the parents, and not the traits themselves. Nevertheless, Hippocrates’ theory influenced biology until well into the 1800s. It was incorporated into an early theory of evolution proposed by the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck around 1800, and was also accepted by Charles Darwin, who developed an alternative theory—the theory of evolution by natural selection (Chapter 21).

16.1.2 Belief in blending inheritance discouraged studies of hereditary transmission.

Darwin also subscribed to the now-discredited model of blending inheritance, in which traits in the offspring resemble the average of those in the parents. For example, the offspring of plants with blue flowers and those with red flowers should have purple flowers. While traits of offspring are sometimes the average of those of the parents (think of certain cases of human height, for example), the idea of blending inheritance—which implies the blending of the genetic material—as a general rule presents problems. For example, it cannot explain the reappearance of a trait several generations after it apparently “disappeared” in a family, such as red hair or blue eyes.

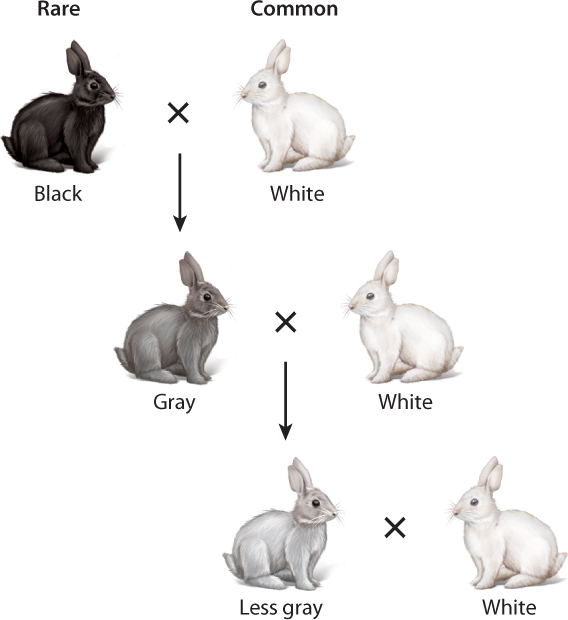

Another difficulty with the concept of blending inheritance is that variation will be lost over time. Consider an example where black rabbits are rare and white rabbits are common (Fig. 16.1). Black rabbits, being rare, are most likely to mate with the much more common white rabbits. If blending inheritance occurs, the result will be gray rabbits. These will also mate with white rabbits, producing even lighter gray rabbits. Over time, the population will end up being all white, or very close to white, and there will be less variation. The only way that black rabbits will be present is if they are re-introduced into the population through mutation or migration. Inheritance will tend to be a homogenizing force, producing in each generation a blend of the original phenotypes. But we know from common experience that variation in most populations is plentiful.

It is ironic that Darwin believed in blending inheritance because this mechanism of inheritance is incompatible with his theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The incompatibility was pointed out by some of Darwin’s contemporaries, and Darwin himself recognized it as a serious problem. The problem with blending inheritance is that rare variants, such as black rabbits in the above example, will have no opportunity to increase in frequency even if they survive and reproduce more than white rabbits, since they gradually disappear over time.

Although Darwin was convinced that he was right about natural selection, he was never able to reconcile his theory with the concept of blending inheritance. Unknown to him, the solution had already been discovered in experiments carried out by Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), an Augustinian monk in a monastery in the city of Brno in what is now the Czech Republic. Mendel’s key discovery was this: It is not traits that are transmitted in inheritance—it is genes that are transmitted.

16-3