48.1 THE ANTHROPOCENE PERIOD

Increasingly, scientists refer to the modern era as the Anthropocene Period, emphasizing the dominant (and, in part, conscious) impact of humans on the Earth. Our impact is partly a consequence of our sheer numbers, which in turn drive our energy and land use, but it also reflects the individual and societal choices we make.

48.1.1 Humans are a major force on the planet.

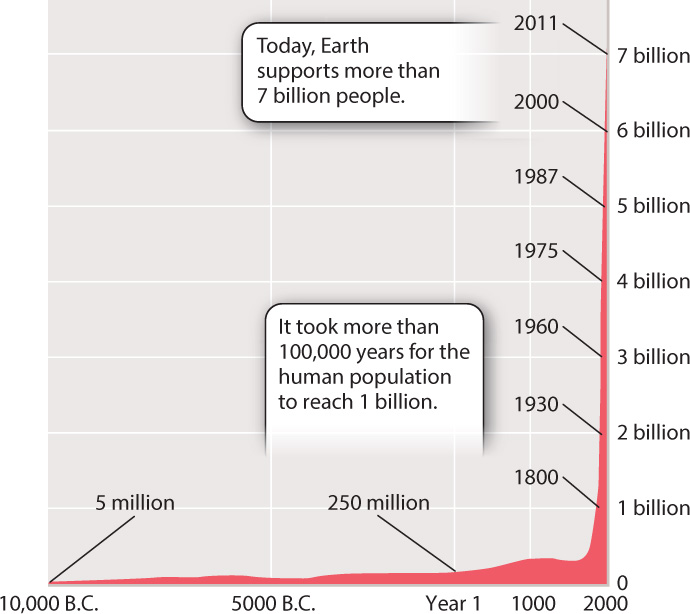

There are more humans than ever before, and our numbers are climbing rapidly. A world that had about 500 million inhabitants when Christopher Columbus set sail in 1492 now supports more than 7 billion people (Fig. 48.1). By the time you retire, our numbers will probably exceed 9 billion.

Question Quick Check 1

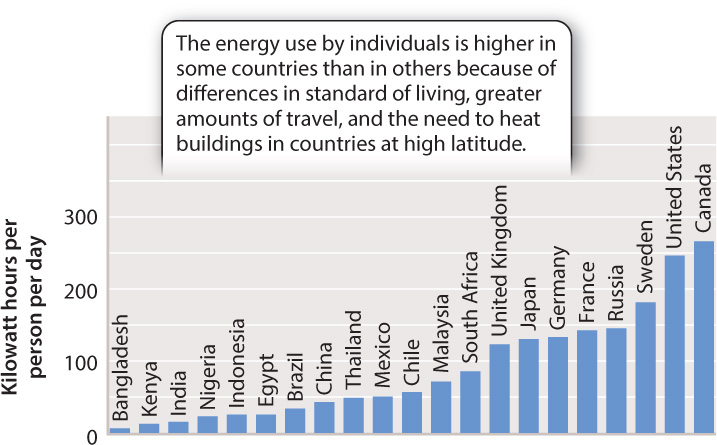

34HEmg21snInHP1BSrJiz/N/RDzcv04MlUoG7TgBY3xTL+xc4GxlAeCLccJkfcyP3kcp57ZURWs2A5O8QfwfQUazIuLfRL6ubFJ5yuo1+AfMkrW2lBoNsirY6CoGJ/brLTQg3Yp06w46arhuJnFj7zmUwDYe3q5OfNtocj3RTdV0iJCc4YSp9WUyF+qXAl3t85I/OQmSHD9Q8ZUzn3kkKo0cpkDaVvQpLg/EWMDAoxFNz9ZrWlBkDogPv8pR3IVlnQfZ/8vDfa8=Of course, population size doesn’t tell the whole story. Whether driving a car, living in a heated apartment, plugging in a computer or television, or eating fruit shipped from another hemisphere, you use a great deal more energy than your ancestors did. To give just one example, it has been suggested that the electrical outlets in our homes let us accomplish about the same amount of work performed by 30 servants in a Roman villa. Fig. 48.2 shows annual per capita energy use in selected countries. Energy use by individuals varies greatly from one part of the world to another. Americans, Canadians, Europeans, and Australians live energy-intensive lives, whereas populations in rural Africa and parts of Asia consume relatively little energy per person.

Our direct use of energy, however, reflects only part of our impact on the planet. Nearly everything we use requires both land and energy. All of us consume food grown in fields, fertilized and harvested through energy, and shipped to a local store. We live in houses built of wood, brick, and stone, and use clothing, furniture, and appliances fashioned from plant materials grown in fields and forests or from minerals extracted from the Earth by mining. It takes land to grow plants, and energy to sow seeds, make and distribute fertilizer, harvest useful materials, and manufacture, ship, and clean the finished products.

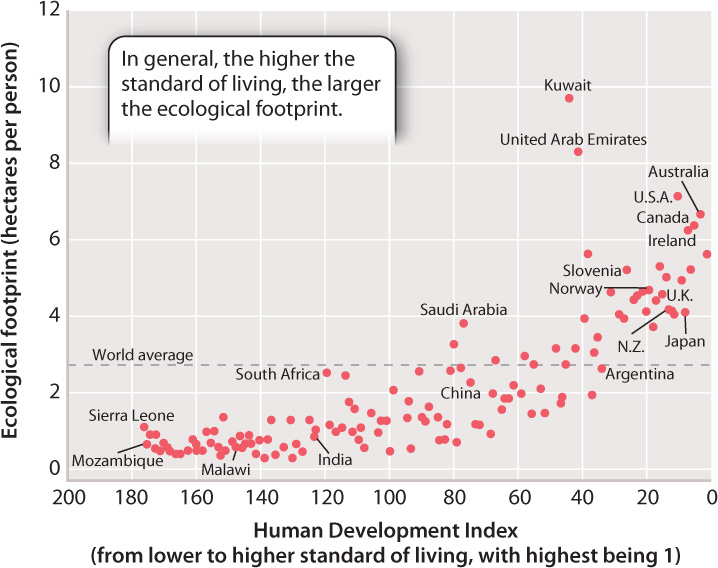

The concept of the ecological footprint is an attempt to quantify our individual claims on global resources by adding up all the energy, food, materials, and services we use and estimating how much land is required to provide those resources. Fig. 48.3 plots the average ecological footprint per person against a ranking of the Human Development Index, a measure of standard of living maintained by the United Nations, for many countries. Not surprisingly, developed countries tend to have large ecological footprints—it takes about 7 hectares of land to support an average American, more than 6 to support an average Australian. In contrast, in many parts of Asia and Africa, only a single hectare supports the average citizen.

In many countries, living standards have risen over the past 50 years, nearly always increasing the mean ecological footprint of their citizens. By some estimates, the total ecological footprint of humanity now exceeds the actual surface area of the Earth. Taken together, then, trends in population size and the ecological footprint highlight both the remarkable technological successes of the past century and the challenges we face as citizens, policy makers, scientists, and engineers in the decades to come.