UNDERSTANDING WRITING PORTFOLIOS.

first time assembling a portfolio?

UNDERSTANDING WRITING PORTFOLIOS. As assignments, portfolios vary enormously in what they aim to do and how they achieve their goals. Some collections serve as learning tools for particular courses, supporting students as they develop sound writing habits; not incidentally, they also provide material for helpful assessments of writing skills. Portfolios in writing classes, which are now usually compiled online, typically include some of the following elements:

Literacy narratives or statements of goals

Literacy narratives or statements of goals Brainstorming/prewriting activities for individual assignments

Brainstorming/prewriting activities for individual assignments Research logs and maps or annotated bibliographies

Research logs and maps or annotated bibliographies Topic proposals and comments

Topic proposals and comments First drafts and revisions, with the writer’s reflections

First drafts and revisions, with the writer’s reflections Peer and instructor comments

Peer and instructor comments Final drafts, with the writer’s reflections

Final drafts, with the writer’s reflections Writer’s midcourse and/or final assessments of learning goals

Writer’s midcourse and/or final assessments of learning goals Additional documents or media materials selected by the writer

Additional documents or media materials selected by the writer A holistic assessment of the portfolio by the teacher (rather than grading of individual items)

A holistic assessment of the portfolio by the teacher (rather than grading of individual items)

Instructors and classmates may play a role at every stage of the composing process, especially when the portfolio is developed online.

In other situations, materials collected in a portfolio provide evidence that a student has mastered specific writing, research, or even media proficiencies required for a job or professional advancement. Such career portfolios (for example, for prospective teachers) may stretch across a sequence of courses, whole degree programs, or college careers. Owners of the portfolio usually have some responsibility for shaping their collection, but certain elements may be recommended or mandated, such as the following:

A personal statement or profile describing accomplishments and learning trajectory as well as career goals

A personal statement or profile describing accomplishments and learning trajectory as well as career goals Work that illustrates mastery of a subject matter

Work that illustrates mastery of a subject matter Evidence of proficiency in specific technical or research skills

Evidence of proficiency in specific technical or research skills Written reflections on specific issues in a field, such as philosophy, diversity, or professional ethics

Written reflections on specific issues in a field, such as philosophy, diversity, or professional ethics Assessments, evaluations, and outsider comments

Assessments, evaluations, and outsider comments Documents that illustrate skills in writing, media, technology, or other areas

Documents that illustrate skills in writing, media, technology, or other areas

This list is partial. College programs that require career or degree portfolios typically offer detailed specifications, criteria of evaluation, templates, and lots of support.

Take charge of the portfolio assignment. Many students are intimidated by the prospect of assembling a writing portfolio. But you won’t have a problem if, right from the start, you study the instructions for the assignment, ask any nagging questions, figure out your responsibilities, and get hands-

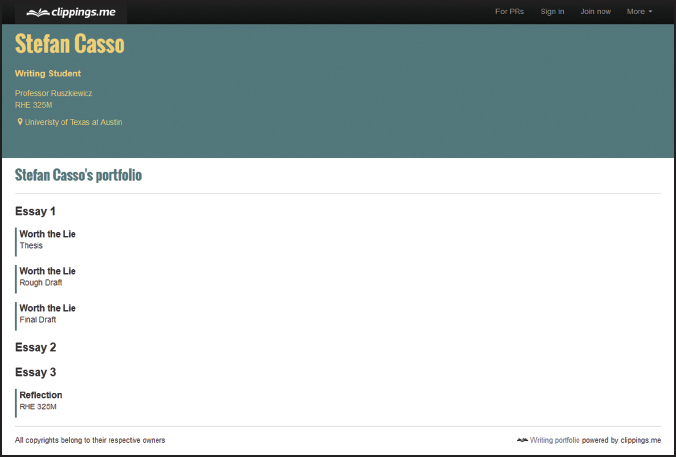

Here’s where you can start: the dashboard screen of a typical online portfolio program.

Clippings.me.

If you are submitting a portfolio in paper form, study the specifications carefully. Then, right from the start, settle on a template for all your submissions: consistent margins, fonts, headings, headers, pagination, captions, and so on. (You might simply adhere to MLA or APA guidelines.) Your work will be more impressive if you give careful attention to design.

Appreciate the audiences for a portfolio. Portfolios are usually mandated by instructors or institutions, and the work you present is likely to influence a grade, certification, or even a job opportunity. Fortunately, such readers will typically offer clear-

You’ll often prepare a portfolio in the company of classmates and you should be grateful when that is the case. Since they are in the same boat, they can keep you grounded and you can usually count on them for timely feedback and even encouragement. Respond in kind. In the long run, you may learn as much from these rough-

One important audience for a portfolio remains: yourself. Creating a portfolio will underscore what it takes to be a writer, highlighting all your moves and making you more conscious of these choices. By discovering strengths and confronting weaknesses, you’ll really learn the craft. So treat the portfolio as an opportunity, not just another long assignment.

Present authentic materials. A writing portfolio demonstrates a process of learning, not a glide path to perfection. So be honest about what you post there, from topic proposals that feel reckless to first drafts that flop grandly. Your instructor will probably be more interested in your development as a writer than in any particular texts you produce: It’s your overall performance that will be assessed, not a single, isolated assignment. Think of your portfolio as a movie, not a snapshot.

When you are allowed to choose what to include, look for materials that tell an important or illustrative story, from topic proposal to first draft to final version. Remember, too, that you can control this narrative (somewhat) through your reflections on these pieces. Here’s how one student takes up that self-

Honestly, on the first day of English 109, I was not a happy student; I had failed the University of Waterloo English Proficiency Exam. Although I told everyone it was not a big deal after it happened, deep down I was bitter. So, signing up for this class to avoid retaking the proficiency exam, I decided to use the course to prove I was not illiterate. The Writing Clinic was wrong to think I was incompetent — a fifty-

Take reflections seriously. Several times during a semester or at various stages in the writing process, an instructor may require you to comment on your own work. Here, for example, is a brief reflective paragraph that accompanied the first draft of Susan Wilcox’s “Marathons for Women,” a report that appears in Chapter 2:

I focused my paper on the evolution of women in marathoning and the struggle for sporting equality with men. I had problems in deciding which incidents to include and which to ignore. Additionally, I’m expecting to hear back from some marathoners so I can possibly include their experiences in my paper; however, none of them have gotten back to me yet. When they do return the interview questions, I’ll have to decide what, if anything, to remove from the paper to make room for personal anecdotes. Finally, I need some work on my introduction and conclusion. What do the current versions lack?

Like Susan, you might use the reflection to ask classmates for specific advice or for editing suggestions.

Most reflections for a portfolio will be lengthier and more evaluative. An instructor might ask for an explanatory comment after the final version of a paper is submitted. You can talk about items such as the following:

Your goals in writing a paper and how well you have met them

Your goals in writing a paper and how well you have met them How you have defined your audience/readers and how you’ve adjusted your paper for them

How you have defined your audience/readers and how you’ve adjusted your paper for them The strategies behind your organization or style

The strategies behind your organization or style How you have addressed problems pointed out by your instructor or peer editors

How you have addressed problems pointed out by your instructor or peer editors What you believe succeeds and what you’d like to have handled better

What you believe succeeds and what you’d like to have handled better What specifically you learned from composing the paper

What specifically you learned from composing the paper

Don’t try to answer all these questions. Give your reflection a point or focus. But your comments should be candid: An instructor will want to know both what you have learned and what you intend to work on more in subsequent assignments.

If asked to compose a midcourse evaluation or a final reflection, broaden your scope and think about the trajectory of your learning across a series of activities and assignments. Again, your instructor may specify what form this comprehensive reflection should take. Some instructors will ask focused questions, others may tie your responses to a specific learning rubric, and still others may even encourage you to write a letter. Here are some questions to think about on your own:

What were your original goals for the writing course, and how well have you met them?

What were your original goals for the writing course, and how well have you met them? What types of audiences do you expect to address in the future, and how prepared are you now to deal with them?

What types of audiences do you expect to address in the future, and how prepared are you now to deal with them? What strategies of organization and style have you mastered?

What strategies of organization and style have you mastered? What did you gain from the responses and advice of classmates?

What did you gain from the responses and advice of classmates? What exactly did you learn during the term?

What exactly did you learn during the term? What goals do you have for the writing you expect to do in the future?

What goals do you have for the writing you expect to do in the future?

If space permits, illustrate your points with examples from your papers or from comments you have received from classmates. For a sample midsemester course reflection, see “Examining a model”.