High, Middle, and Low Style

Chapter Opener

32

define your style/refine your tone

High, Middle, and Low Style

We all have an ear for the way words work in sentences and paragraphs, for the distinctive melding of voice, tone, rhythm, and texture some call style. You might not be able to explain exactly why one paragraph sparkles and another is as flat as day-

In fact, there are as many styles of writing as of dress. In most cases, language that is clear, active, and economical will do the job. But even such a bedrock style has variations. Since the time of the ancient Greeks, writers have imagined a “high” or formal style at one end of a scale and a “low” or colloquial style at the other, bracketing a just-

Even dining has distinct levels of style and formality you grasp immediately.

Top: Anna Brykhanova/Getty Images. Center: Steve Debenport/E+ Collection/Getty Images. Bottom: Mary Altaffer/Associated Press.

John Cole, courtesy Cagle Cartoons.

Use high style for formal, scientific, and scholarly writing. You will find high style in professional journals, scholarly books, legal briefs, formal addresses, many newspaper editorials, some types of technical writing, and even traditional wedding invitations. Use it yourself when a lot is at stake — in a scholarship application, for example, or a job letter, term paper, or thesis. High style is signaled by some combination of the following features — all of which can vary.

Serious or professional subjects

Serious or professional subjects Knowledgeable or professional audiences

Knowledgeable or professional audiences Impersonal point of view signaled by dominant, though not exclusive, third-

Impersonal point of view signaled by dominant, though not exclusive, third-person (he, she, it, they) pronouns  Relatively complex and self-

Relatively complex and self-consciously patterned sentences (that display parallelism, balance, repetition)  Sophisticated or professional vocabulary, often abstract and technical

Sophisticated or professional vocabulary, often abstract and technical Few contractions or colloquial expressions

Few contractions or colloquial expressions Conventional grammar and punctuation; standard document design

Conventional grammar and punctuation; standard document design Formal documentation, when required, often with notes and a bibliography

Formal documentation, when required, often with notes and a bibliography

The following example is from a scholarly journal. The article uses a formal scientific style, appropriate when an expert in a field is writing for an audience of his or her peers.

Temperament is a construct closely related to personality. In human research, temperament has been defined by some researchers as the inherited, early appearing tendencies that continue throughout life and serve as the foundation for personality (A. H. Buss, 1995; Goldsmith et al., 1987). Although this definition is not adopted uniformly by human researchers (McCrae et al., 2000), animal researchers agree even less about how to define temperament (Budaev, 2000). In some cases, the word temperament appears to be used purely to avoid using the word personality, which some animal researchers associate with anthropomorphism. Thus, to ensure that my review captured all potentially relevant reports, I searched for studies that examined either personality or temperament.

— Sam D. Gosling, “From Mice to Men: What Can We Learn About Personality from Animal Research?” Psychological Bulletin

Technical terms introduced and defined.

Sources documented.

Perspective generally impersonal — though I is used.

The following excerpt from a 2013 Presidential Proclamation marking National Arts and Humanities Month also uses a formal style. The occasion calls for an expressive reflection on a consequential subject.

Throughout our history, America has advanced not only because of our people’s will or our leaders’ vision, but also because of paintings and poems, stories and songs, dramas and dances. These works open our minds and nourish our souls, helping us understand what it means to be human and what it means to be American. . . .

Opening is general and serious—

Our history is a testament to the boundless capacity of the arts and humanities to shape our views of democracy, freedom, and tolerance. Each of us knows what it is like to have our beliefs changed by a writer’s perspective, our understanding deepened by a historian’s insight, or our waning spirit lifted by a singer’s voice. These are some of the most striking and memorable moments in our lives, and they reflect lasting truths — that the arts and humanities speak to everyone and that in the great arsenal of progress, the human imagination is our most powerful tool.

Vocabulary is learned and dignified.

Ideas expressed are abstract and uplifting.

Ensuring our children and our grandchildren can share these same experiences and hone their own talents is essential to our Nation’s future. Somewhere in America, the next great author is wrestling with a sentence in her first short story, and the next great artist is doodling in the pages of his notebook. We need these young people to succeed as much as we need our next generation of engineers and scientists to succeed. And that is why my Administration remains dedicated to strengthening initiatives that not only provide young people with the nurturing that will help their talents grow, but also the skills to think critically and creatively throughout their lives.

Voice is “presidential,” speaking for the nation.

This month, we pay tribute to the indelible ways the arts and humanities have shaped our Union. Let us encourage future generations to carry this tradition forward. And as we do so, let us celebrate the power of artistic expression to bridge our differences and reveal our common heritage.

— Presidential Proclamation, National Arts and Humanities Month, September 20, 2013

Final paragraph evokes well-

Use middle style for personal, argumentative, and some academic writing. This style, perhaps the most common, falls between the extremes and, like the other styles, varies enormously. It is the language of journalism, popular books and magazines, professional memos and nonscientific reports, instructional guides and manuals, and most commercial Web sites. Use this style in position papers, letters to the editor, personal statements, and business e-

Full range of topics, from serious to humorous

Full range of topics, from serious to humorous General audiences

General audiences Range of perspectives, including first-

Range of perspectives, including first-person (I ) and second- person ( you) points of view  Typically, a personal rather than an institutional voice

Typically, a personal rather than an institutional voice Sentences in active voice that vary in complexity and length

Sentences in active voice that vary in complexity and length General vocabulary, more specific than abstract, with concrete nouns and action verbs and with unfamiliar terms or concepts defined

General vocabulary, more specific than abstract, with concrete nouns and action verbs and with unfamiliar terms or concepts defined Informal expressions, occasional dialogue, slang, and contractions, when appropriate to the subject or audience

Informal expressions, occasional dialogue, slang, and contractions, when appropriate to the subject or audience Conventional grammar and reasonably correct formats

Conventional grammar and reasonably correct formats Informal documentation, usually without notes

Informal documentation, usually without notes

In the following excerpt from an article that appeared in the popular magazine Psychology Today, Ellen McGrath uses a conversational but serious middle style to present scientific information to a general audience.

Families often inherit a negative thinking style that carries the germ of depression. Typically it is a legacy passed from one generation to the next, a pattern of pessimism invoked to protect loved ones from disappointment or stress. But in fact, negative thinking patterns do just the opposite, eroding the mental health of all exposed.

Vocabulary is sophisticated but not technical.

When Dad consistently expresses his disappointment in Josh for bringing home a B minus in chemistry although all the other grades are A’s, he is exhibiting a kind of cognitive distortion that children learn to deploy on themselves — a mental filtering that screens out positive experience from consideration.

Familiar example (fictional son is even named) illustrates technical term: cognitive distortion.

Phrase following dash offers further clarification helpful to educated, but nonexpert, readers.

Or perhaps the father envisions catastrophe, seeing such grades as foreclosing the possibility of a top college, thus dooming his son’s future. It is their repetition over time that gives these events power to shape a person’s belief system.

— “Is Depression Contagious?,” July 1, 2003

The middle style works especially well for speakers addressing actual audiences. Compare the informal and personal style of Michelle Obama, in her role as first lady, advocating for arts education at an awards luncheon to the more stately language her husband uses in his presidential proclamation, also on the subject of the arts (p. 402):

So for every Janelle Monae [an artist recognized at the luncheon], there are so many young people with so much promise [that] they never have the chance to develop. And think about how that must feel for a kid to have so much talent, so much that they want to express, but it’s all bottled up inside because no one ever puts a paintbrush or an instrument or a script into their hand.

Style is personal, with feelings close to the surface.

Think about what that means for our communities, that frustration bottled up. Think about the neighborhoods where so many of our kids live — neighborhoods torn apart by poverty and violence. Those kids have no good outlets or opportunities, so for them everything that’s bottled up — all that despair and anger and fear — it comes out in all the wrong places. It comes out through guns and gangs and drugs, and the cycle just continues.

Sentences and clauses are parallel, rhythmic, and evocatively short.

But the arts are a way to channel that pain and frustration into something meaningful and productive and beautiful. And every human being needs that, particularly our kids. And when they don’t have that outlet, that is such a tremendous loss, not just for our kids, but for our nation. And that’s why the work you all are doing is so important.

— Remarks by the First Lady at the Grammy Museum’s Jane Ortner Education Award Luncheon, July 14, 2014

Vocabulary choices are crisp and varied. Note the use of “kids” throughout.

Use a low style for personal, informal, and even playful writing. Don’t think of “low” here in a negative sense: A colloquial or informal style is perfect when you want or need to sound more open and at ease. Low style can be right for your personal e-

Everyday or off-

Everyday or off-the- wall subjects, often humorous or parodic  In-

In-group or specialized readers  Highly personal and idiosyncratic points of view; lots of I, me, you, us, and dialogue

Highly personal and idiosyncratic points of view; lots of I, me, you, us, and dialogue Shorter sentences and irregular constructions, especially fragments

Shorter sentences and irregular constructions, especially fragments Vocabulary from pop culture and the street — idiomatic, allusive, and obscure to outsiders

Vocabulary from pop culture and the street — idiomatic, allusive, and obscure to outsiders Colloquial expressions resembling speech

Colloquial expressions resembling speech Unconventional grammar and mechanics and alternative formats

Unconventional grammar and mechanics and alternative formats No systematic acknowledgment of sources

No systematic acknowledgment of sources

Here’s a movie review from Rolling Stone written in the easy, informal style expected by (and probably used by) its readers.

JOBS

PETER TRAVERS

AUGUST 15, 2013

Casting Ashton Kutcher as Apple’s mercurial trailblazer, Steve Jobs, could have backfired big-

Opening paragraph flirts with middle-

As a movie, Jobs is a decidedly mixed bag. Director Joshua Michael Stern (Swing Vote) and newbie screenwriter Matt Whiteley check off boxes in Jobs’s life like they’re connecting the dots. Oddly, the film doesn’t include Jobs’s 2011 death from pancreatic cancer at fifty-

Tone shifts in a more colloquial second paragraph: mixed bag, newbie, connecting the dots.

Jobs, the barefoot hippie and Reed College dropout, sets up shop with his geek buds in the California garage of his adoptive parents. That’s where he and Steve “The Woz” Wozniak (Josh Gad) create Apple and start a revolution. Jobs loses the business. Then he wins it back. It plays like a Jobs Wiki page, including young Steve kicking his girlfriend Chrisann (Ahna O’Reilly) to the curb and initially disowning their daughter.

Sentence structures imitate informal talk.

The kick comes in watching the man at work, where his blunt style wins few friends but real respect. Kutcher, rising to the occasion, makes every moment count. The skilled Gad looks eager to take him on, but the Woz is a painfully underwritten role. Jobs is a one-

Travers renders a verdict in the final sentence.

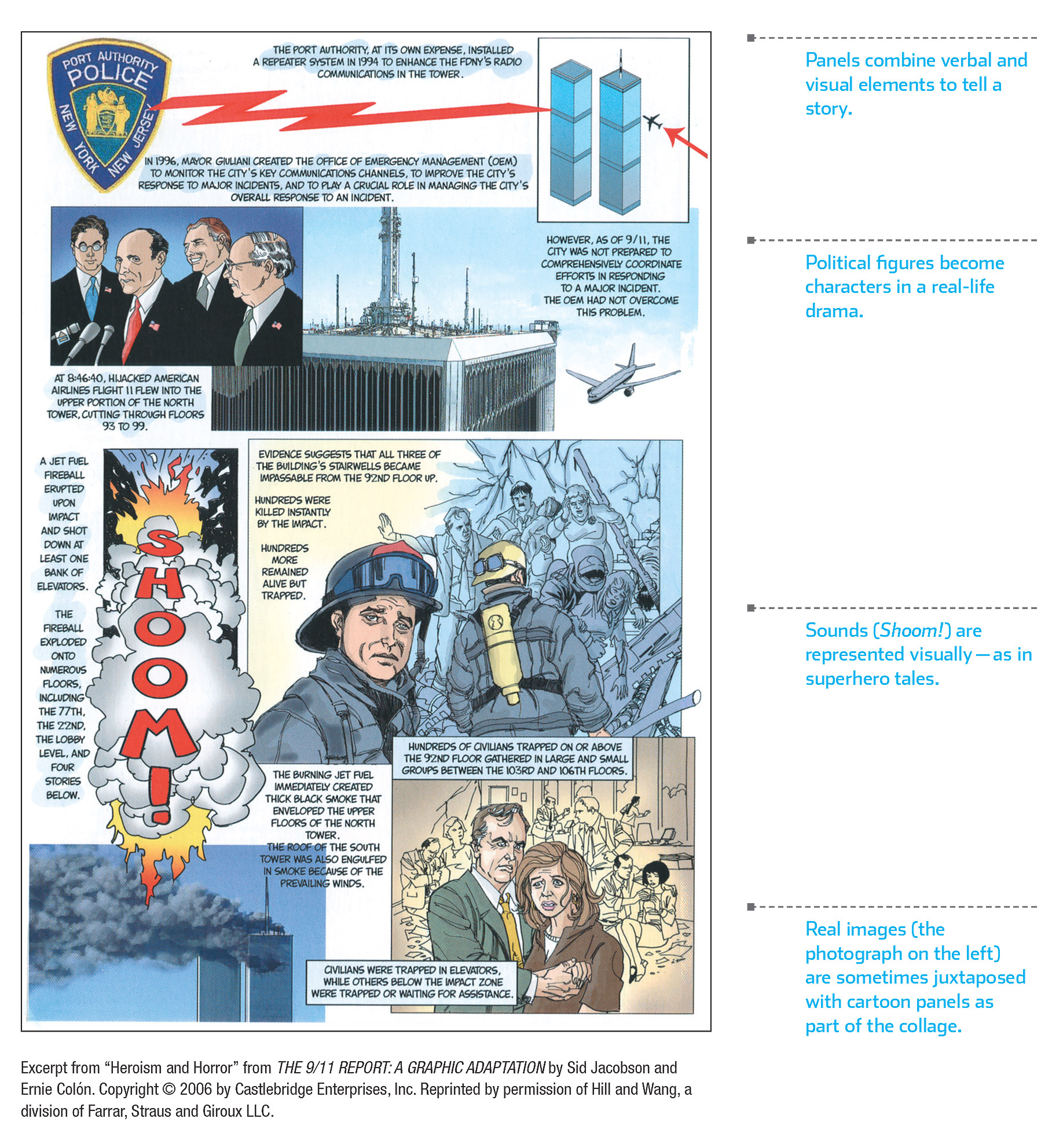

The very serious story told in the 9/11 Commission Report was retold in The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation (p. 407). Creators Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón use the colloquial visual style of a comic book to make the formidable data and conclusions of a government report accessible to a wider audience. For more on choosing a genre, see the Introduction.

For an activity on appropriate language, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Appropriate Language

For an activity on appropriate language, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Appropriate Language