Doing Field Research

Chapter Opener

39

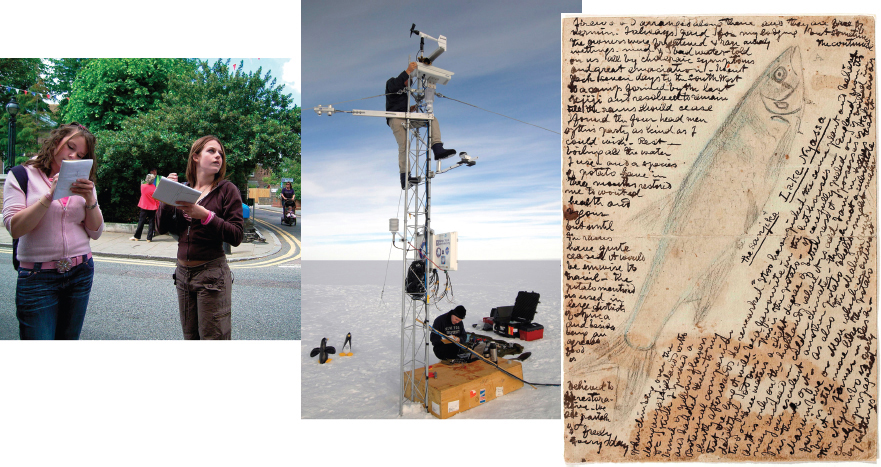

interview and observe

Doing Field Research

While most writing you do will be built on the work of others —that is, their books, articles, and fact-

Interview people with unique knowledge of your subject. When considering whether an interview makes sense for your project, ask yourself this important question: “What do I expect to learn from the interviewee?” If the information you seek is easily available online or in print, don’t waste everyone’s time going through with an interview. If, on the other hand, this person offers a fresh perspective on your topic, a personal interview could advance your research.

Interviews can be written or spoken. Written interviews, whether by e-

Request an interview formally by phone, confirming it with a follow-

Request an interview formally by phone, confirming it with a follow-up message.  Give your subjects a compelling reason for meeting or corresponding with you; briefly explain your research project and why their knowledge or experience is important to your work.

Give your subjects a compelling reason for meeting or corresponding with you; briefly explain your research project and why their knowledge or experience is important to your work. Let potential interviewees know how you chose them as subjects. If possible, identify a personal reference — that is, a professor or administrator who can vouch for you.

Let potential interviewees know how you chose them as subjects. If possible, identify a personal reference — that is, a professor or administrator who can vouch for you. Prepare a set of purposeful interview questions. Don’t try to wing it.

Prepare a set of purposeful interview questions. Don’t try to wing it. Think about how to phrase questions to open up the interview. Avoid queries that can be answered in one word. Don’t ask, Did you enjoy your years in Asia? Instead, lead with, What did you enjoy most about the decade you spent in Tokyo?

Think about how to phrase questions to open up the interview. Avoid queries that can be answered in one word. Don’t ask, Did you enjoy your years in Asia? Instead, lead with, What did you enjoy most about the decade you spent in Tokyo?

Start the interview by thanking the interviewee for his or her time and providing a very brief description of your research project.

Start the interview by thanking the interviewee for his or her time and providing a very brief description of your research project. Keep a written record of material you intend to quote. If necessary, confirm the exact wording with your interviewee.

Keep a written record of material you intend to quote. If necessary, confirm the exact wording with your interviewee. End the interview by again expressing your thanks.

End the interview by again expressing your thanks. Follow up with a thank-

Follow up with a thank-you note or e- mail and, if the interviewee’s contributions were substantial, send him or her a copy of the final research paper.  In your paper, give credit to any people interviewed by documenting the information they provided. (understand citation styles)

In your paper, give credit to any people interviewed by documenting the information they provided. (understand citation styles)

For an interview conducted in person, arrive at the predetermined meeting place on time and dressed professionally. If you wish to record the interview, be sure to ask permission first.

If you conduct your interview in writing, request a response by a certain date — one or two weeks is reasonable for ten questions. Refer to Chapter 13 for e-

For telephone interviews, call from a place with good reception, where you will not be interrupted. Your cell phone should be fully charged or plugged in.

Your Turn

Prepare a full set of questions you would use to interview a classmate about some academic issue — for example, study habits, methods for writing papers, or career objectives. Think about how to sequence your questions, how to avoid one-

When you are done, write a one-

Make careful and verifiable observations. The point of systematic observation is to provide a reliable way of studying a narrowly defined activity or phenomenon. But in preparing reports or arguments that focus on small groups or local communities, you might find yourself without enough data to move your claims beyond mere opinion.

For example, an anecdote or two won’t persuade administrators that community rooms in the student union are being scheduled inefficiently. But you could conduct a simple study of these facilities, showing exactly how many student groups use them and for what purposes, over a given period of time.

This kind of evidence usually carries more weight with readers, who can decide whether to accept or challenge your numbers.

Some situations can’t be counted or measured as readily as the one described above. If you wanted, let’s say, to compare the various community rooms to determine whether those with windows encouraged more productive discussions than rooms without, your observations would be “softer” and more qualitative. You might have to describe the tone of speakers’ voices or the general mood of the room. But numbers might play a part; you could, for instance, track how many people participated in the discussion or the number of tasks accomplished during the meeting.

To avoid bias in their observations, many researchers use double-

In addition to careful and objective note-

Learn more about fieldwork. In those disciplines or college majors that use fieldwork, you will find guides or manuals to explain the details of such research procedures. You will also discover that fieldwork comes in many varieties, from naturalist observations and case studies to time studies and market research.

A double-

| OBSERVABLE DATA | COMMENTARY |

| 9/12/11 | |

| 2 P.M. | |

| Meeting of Entertainment Committee | |

| Room MUB210 (no windows) | |

| 91 degrees outside | Heat and lack of a/c probably |

| Air conditioning broken | making everyone miserable. |

| People appear quiet, tired, hot |